News

Garber Privately Tells Faculty That Harvard Must Rethink Messaging After GOP Victory

News

Cambridge Assistant City Manager to Lead Harvard’s Campus Planning

News

Despite Defunding Threats, Harvard President Praises Former Student Tapped by Trump to Lead NIH

News

Person Found Dead in Allston Apartment After Hours-Long Barricade

News

‘I Am Really Sorry’: Khurana Apologizes for International Student Winter Housing Denials

Teach for America, Yourself, and Goldman Sachs

After your stint at Teach for America, a two-year post-undergraduate teaching program, you decided to leave the academic world behind and work in New York City. Where are you most likely to be employed? Goldman Sachs.

But we will get back to that.

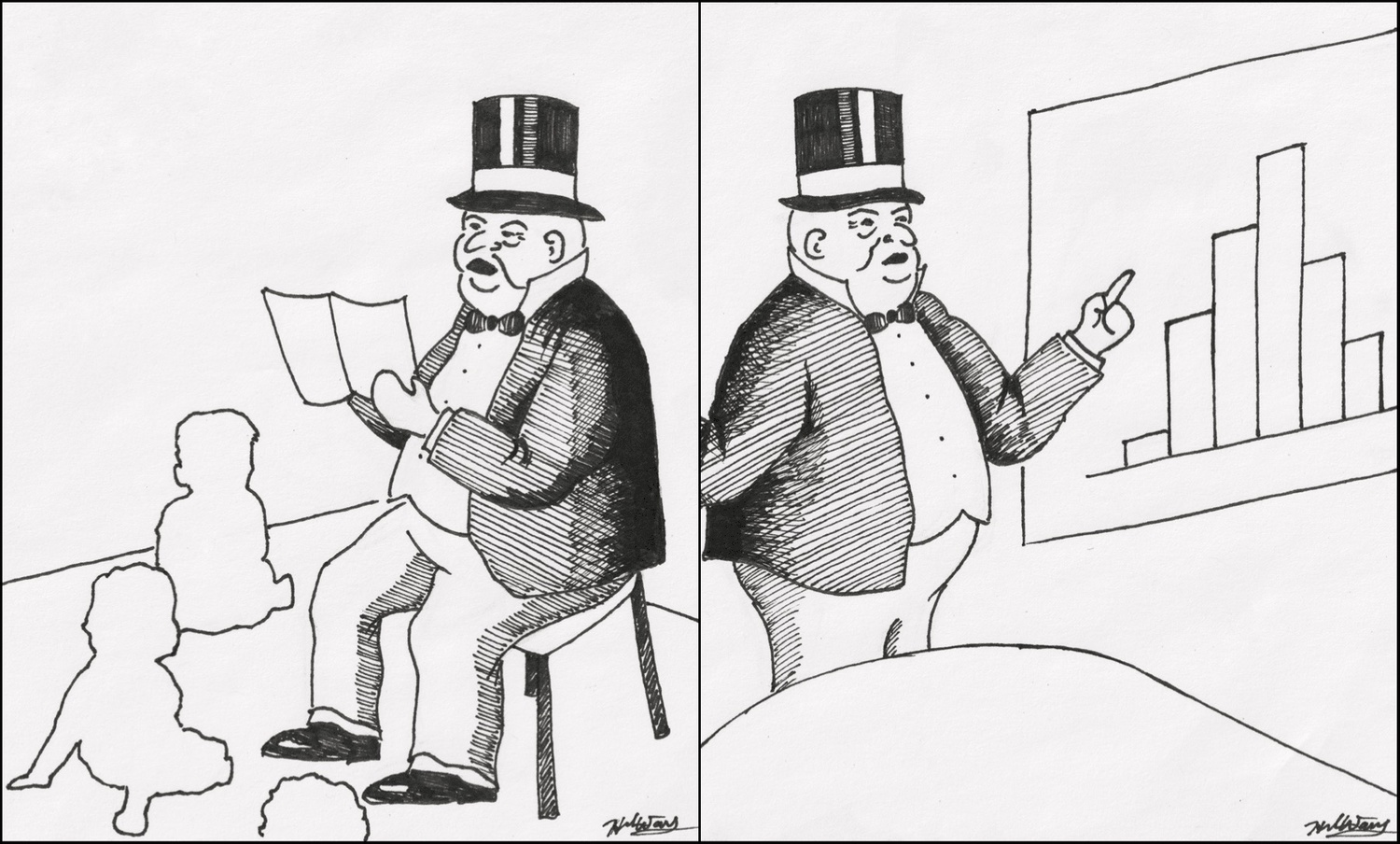

We need to change the pernicious idea that public service is on a separate moral level of “goodness” because it is undertaken purely for selfless reasons. This piece of philosophical fiction is at odds with reality, so much so that it only entrenches the reality it seeks to deny. It is only by acknowledging and appealing to the selfish instincts of people that we can fulfill the goal that should be at the heart of service — serving others.

The selfless ethic of service has many intellectual sources, but I suspect that it finds its purest expression in Kantian moral philosophy. Kant viewed moral action as a dispassionate adherence to moral law. Through enlightened reason we freely choose to do the right thing only because it's objectively the right thing to do, not because of any personal benefits. In fact, Kant says if we act for any selfish reasons we can no longer claim to have acted “morally” since the good result of our actions are only the by-product of our self-interest.

These days few people are as Kantian as Kant, but his insights are embedded in our perception of public service. Public service is noble because it involves a sacrifice of self-interest. Public servants transcend self-interest because they cast it aside.

Yet this praise of the selfless public career path presumes and only confirms the domination of the private, for-profit career. Only 17 percent of the 2019 class had finalized careers in nonprofits, non-governmental organizations, or governments at the time of graduation. This statistic is actually quite impressive. Only about a quarter of Harvard students volunteer with the Phillips Brooks House Association in a given year, and about the same percentage of my class volunteered for the Day of Service. The problem with public service is that this neo-Kantian ethic of service only has two ways of persuasion: praise and shame, both of which are clearly incapable of motivating a majority of talented students.

I contend that self-interest is what consistently causes college students to wake up at early hours and be on their peak mental game for an entire day. An affinity and passion for the demanding workload is necessary for success in both the private and public spheres, but that passion doesn’t last forever. Sometimes people wake up in the mornings because of the work they do, but other times they wake up in spite of the work they must do, and just try and get through the day. It is during these moments of apathy that the private sector has its greatest allure. Economic self-interest works better to motivate than any praise and shame associated with moral duty. Even if the ideal of selfless service attracts some to the public sphere, it has no way of guaranteeing continued dedication, except through praise and shame.

Which brings us back to Teach for America. Teach for America critics, both within and outside the organization, view the program’s own preparation as inadequate to produce quality teachers. Teachers report feeling ashamed for being unable to teach at the level which they aspired to, and burnout is a real concern for corps members. Some members do develop lifetime passions for teaching and continue on in different advisory contexts, but others, disillusioned by their time as teachers, leave the academic world behind for more lucrative pastures. As such, critics come to view the program on the whole as glorified “resume padding”, in which teachers don’t even fulfill those responsibilities that they put on their resume in the first place.

Where the neo-Kantians see dereliction of duty or the moral degradation of service, I see opportunity. Partnerships with Goldman Sachs are not what is wrong with Teach for America, but its greatest potential asset.

The necessary accompaniment of the pursuit of self-interest is competition — we can’t all get what we want. Teach for America’s problem is not the intrusion of self-interest, but its unwillingness to harness this self-interest and the productive fruits of competition for the students that it serves. Teach for America should expand its partnerships with Goldman and other prestigious companies in the private sector, so much so that it almost becomes a backdoor to them. However, it should make offers contingent upon so many objective teaching metrics — test scores, student reviews and peer reviews — that the only way for corps members to get these jobs is to be good teachers.

The best part about this suggestion is that the competition will spur other teachers to new heights. Shame from failure to live up to an impossible ideal is one thing, but shame from potentially performing worse at one’s own vocation than future investment bankers is another.

The competition induced by self-interest doesn’t cheapen service, it revitalizes it. Service should be for the people whom we serve, not for ourselves, because we can’t always live up to the best of our intentions, and it doesn’t make sense to hold ourselves to an unattainable ideal. Instead, if service is about impacting others, we should be willing, and even obligated, to use every incentive we have to improve the quality of service that is provided.

Eric Yang ’22, is a History concentrator in Leverett House. His column appears on alternate Tuesdays.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.