News

Harvard Grad Union Agrees To Bargain Without Ground Rules

News

Harvard Chabad Petitions to Change City Zoning Laws

News

Kestenbaum Files Opposition to Harvard’s Request for Documents

News

Harvard Agrees to a 1-Year $6 Million PILOT Agreement With the City of Cambridge

News

HUA Election Will Feature No Referenda or Survey Questions

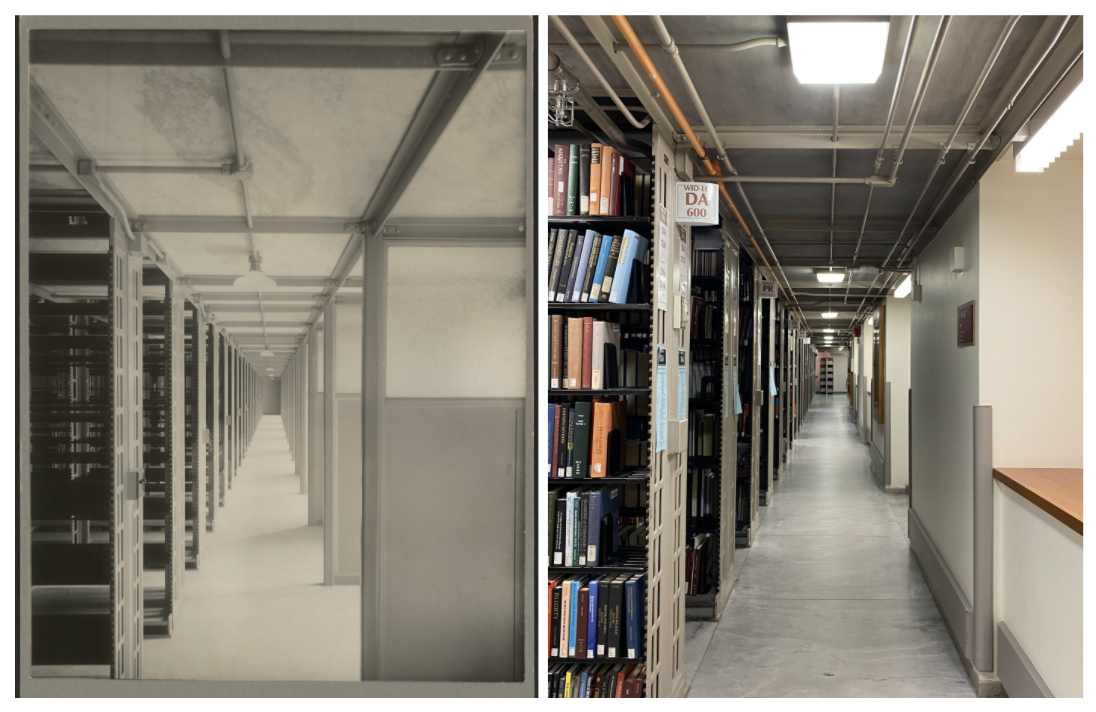

The Friendly Ghosts of Widener Stacks

Only thirty steps separate you from the front door of Widener Library, although it seems like so many more as you look up at the building. Looming over Tercentenary Theater, Widener is a hulking, more than a century-old presence that exudes an air of endurance — you can almost feel the building’s age when you’re inside.

Those thirty steps carry extra meaning this fall; many students have long-awaited their return to Harvard’s flagship library — in many ways the center of our campus — since March of 2020.

Emerging from a tragedy, Widener’s endurance is a constant throughout much of Harvard’s modern history. After the Titanic sank in 1912, taking book collector Harry Elkins Widener, Class of 1907, with it, Elkins Widener’s mother Eleanor donated $2 million to Harvard to build a library in memory of her late son. Widener Library — which actually bears the full name of the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library — emerged in 1915 as Harvard’s premier library that houses almost 3.5 million books throughout its cavernous depths.

Widener is a force unto itself, and the students it serves can recognize this. As Elliott Detjen ’24 put it in an interview, “the library, with its centrality on the Yard, commands a certain kind of presence.”

During my first-ever visit to Widener in August, I was impressed by the grandeur of the building that contrasted with the function of the space itself. Widener’s primary function of housing books and circulating materials is set against a backdrop of marble and murals, the often non-flashy action of combing through text to do research and completing problem sets seemingly elevated to the status of art. After all, the inside of Widener bears a striking resemblance to the inside of an art museum, both places replete with old paintings and busts of individuals long gone. Walking through the stacks, I was amazed at how the corridors weaved into labyrinths, fascinated by the sheer number of books that surrounded me, and awed by how old some of them seemed to be.

The study carrels in the stacks don’t exude the same opulence as the rest of the library, but their complexity is in the way they exist as mini-homes for thesis and dissertation writers. As I passed by these carrels, I couldn’t help but notice all the items that were left by the carrels’ users — things like cutlery, toothpaste, blankets, and even rock crystals. Perhaps these items were remnants from March 2020, items left behind by those who were still working on their theses in Widener's carrels when the pandemic shut the library’s doors. The scene was an eerie parallel to Pompeii: I stood surrounded by the microcosmic worlds that the study carrel users had built for themselves, yet with these individuals invisible.

Widener continues to watch the inflow and outflow of students it has seen for over a hundred years, watching one graduating class be replaced by an entering one. For many sophomores, in particular, entering Widener represents a much-desired introduction to campus after missing out on the foundational experience that is getting lost in the library’s corridors and stacks during freshman year.

For Shraddha Joshi ’24, finally being able to go into Widener after a year was reaffirming.

“Having been off of campus for the entire last year, that physical space of being able to go somewhere to study, and particularly being able to go to Widener, I think it's very grounding because it reminds me that I go to Harvard and that I have access to all this wealth of knowledge,” Joshi said in an interview.

Detjen said he saw Widener as a connection to Harvard’s history: “I like the feeling that I'm almost studying among the ranks of several generations of Harvard students who have shared the same space that I have.” Evidence of these generations sits in the carrels themselves.

The seniors — who are about to leave Widener behind in a few short months — have both memories to look back on and memories yet to be created. Noah Dasanaike ’22, a former Crimson Editorial editor, talked about his memories of sitting on Widener’s ledges with friends.

“Since I was a freshman, my friends and I sort of just sat there and just talked to each other, eating Jefe’s together, for long periods of time. My friends then that I did that with are the friends that I still do that with today,” Dasanaike said.

After a year of campus closure, it’s important that we keep the atmosphere of community created by shared experiences, shared spaces, alive. Widener has endured through more than a century — may our ability to keep coming back to Widener, to keep making connections and friends on its steps and in its hallways also endure.

A shared space is special so long as it is actually shared, actually lived and existed in. Next time you feel the urge to study or want to lose yourself in a labyrinth, go to Widener and feel the presence of those next to you and those before you. May you find community as you get lost in the stacks.

Shanivi Srikonda ’24, a Crimson Editorial editor, lives in Quincy House. Her column “Nooks and Crannies” appears on alternate Wednesdays.

Have a suggestion, question, or concern for The Crimson Editorial Board? Click here.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

Related Articles

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

With innovative financial tools combined with financial education, Collegiate empowers students to take control of their finances and build confidence in their money management skills.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

Admit Expert is a premium MBA admissions consulting company, helping candidates secure admission to top B-schools across the globe with significant scholarships.