News

Garber Announces Advisory Committee for Harvard Law School Dean Search

News

First Harvard Prize Book in Kosovo Established by Harvard Alumni

News

Ryan Murdock ’25 Remembered as Dedicated Advocate and Caring Friend

News

Harvard Faculty Appeal Temporary Suspensions From Widener Library

News

Man Who Managed Clients for High-End Cambridge Brothel Network Pleads Guilty

Where Did All The Ideas Go?

Reflections on a "Meh" Election

The Democratic candidate for Senate in Kentucky, Alison Lundergan Grimes, won’t admit that she voted for President Obama in 2012. Democratic gubernatorial nominee Wendy Davis of Texas is taking heat for an attack ad that referenced to her opponent’s disability. Florida’s gubernatorial race was overtaken by “fangate.”

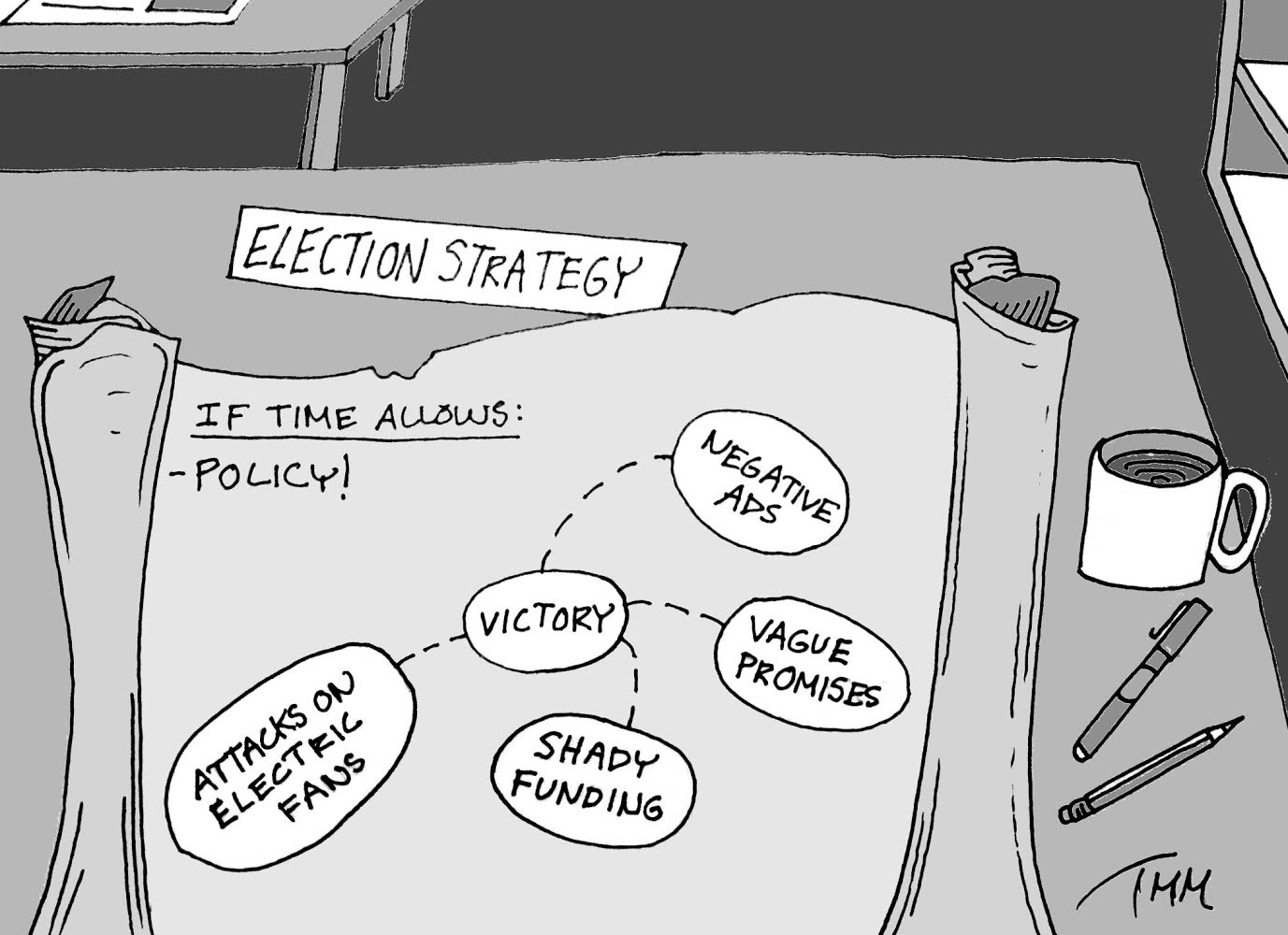

Yes, it has been one of those elections. Dark money. Negative ads. Fans. And, above all, a paucity of ideas.

Newt Gingrich underscored this intellectual deficit, likely without meaning to do so, when he recently penned a short op-ed celebrating the 20th anniversary of his Contract with America, the 1994 document of legislative proposals that helped catapult Republicans to a House majority.

A document like the contract is exactly what this year’s election lacks. As David Brooks wrote about this year’s midterms, “There’s not even a Contract with America, nor many policy suggestions of any sort.” That hole is why this election feels so unfulfilling – and one of the key reasons why it is unlikely to create real change.

Historic elections are often ones with serious ideas on the table. Take, for instance, the United Kingdom’s 1945 election, when the Labour Party under Clement Attlee ousted Winston Churchill’s Conservatives and set about turning Britain into a modern welfare state. Labour’s manifesto was bold, articulating the moral case for left-of-center policies, and offering clear proposals for implementation. In Attlee’s immortal phrase, it aimed to create “free citizens of a great country.”

Some such major elections do not have ideas so front and center, but they are often percolating beneath the surface. During the 1932 U.S. presidential election, the “New Deal” was still a relatively amorphous concept, but its general intellectual provenance was clear, and Roosevelt suggested on several occasions that he wished to preside over a robust expansion of the federal government.

Barack Obama’s election in 2008 might fall into a somewhat similar category. As in 1932, a clear contrast existed between how the two major candidates intended to handle an economic crisis, and how they viewed the role of government in providing services like healthcare. Then-Senator Obama’s bolder ideas, though vague, won the day, and, despite his stumbles, the President has undertaken credible reforms.

Of course, demanding more ideas in an election does not necessarily result in good policies. The Contract with America contained many ideas that were simply bizarre, like the push for a so-called “effective death penalty.” Its welfare reform proposals had disastrous effects during the recession. But ultimately voters responded to it, largely because it offered a blueprint for action, rather than merely a trite collection of slogans. The Contract may have included mostly bad ideas, but ideas they were – clear and actionable, tailored to the times, and ideologically coherent.

Do today’s parties have such serious policy proposals? It depends on the definition of serious, but a quick glance at the travails of their respective congressional caucuses and think tanks suggests they do. After all, Representative Paul Ryan continues to produce budget proposals year after year – though the American public may have hinted at their true feelings about the “Ryan budget” in the 2012 election.

Even more intriguing than the Ryan budget is that of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, which The Economist compared favorably to the Wisconsin Congressman’s in 2011. The most recent iteration of the Progressive Caucus budget, the “Better Off Budget,” is less ambitious in terms of deficit reduction, but retains core features of previous years like cuts in defense spending, increases in public investment, and additional, higher marginal tax rates for high-earners.

Neither the Ryan plan nor the Progressive Caucus budget will become law, but the extent to which members of both parties are running away from such clear articulations of policy is striking. To take two high-profile examples, Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky thinks he can repeal the Affordable Care Act completely and still preserve all its benefits for his constituents; his opponent, the same one who won’t say which Presidential candidate she voted for in 2012, is so afraid of the law that she does not have a “healthcare” section of her issues page.

Both these stances represent the hope that voters, acting viscerally, will make their choice based on instinct and little else. And for now, they will. But if any party wants to implement its vision and end the current status quo of bipartisan misrule, it will have to start telling voters what that vision is.

Nelson L. Barrette '17, a Crimson editorial writer, lives in Winthrop House. His column usually appears on alternate Mondays.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.