News

Nearly 200 Harvard Affiliates Rally on Widener Steps To Protest Arrest of Columbia Student

News

CPS Will Increase Staffing At Schools Receiving Kennedy-Longfellow Students

News

‘Feels Like Christmas’: Freshmen Revel in Annual Housing Day Festivities

News

Susan Wolf Delivers 2025 Mala Soloman Kamm Lecture in Ethics

News

Harvard Law School Students Pass Referendum Urging University To Divest From Israel

Breaking Down the Scarcity Mindset

Have you ever pulled an all-nighter? Do you remember the next day, when a mental fog clouds up your brain and simple tasks get 10 times harder? What if you felt like that every day? Some people do.

In a 2017 experiment, researchers found that simply thinking about an expensive car repair bill significantly worsened the cognitive performance of low-income individuals. These same researchers also studied sugarcane farmers in India, who make the majority of their annual income all at once. At harvest time, the farmers quickly go from poor to relatively rich. The farmers performed much worse on cognitive tests before the harvest when poor than after, despite controlling for stress and other factors. The researchers concluded that poverty “imposes a cognitive load and impedes cognitive capacity” and that these effects are equivalent to losing roughly 13 IQ points — comparable to missing out on a full night of sleep.

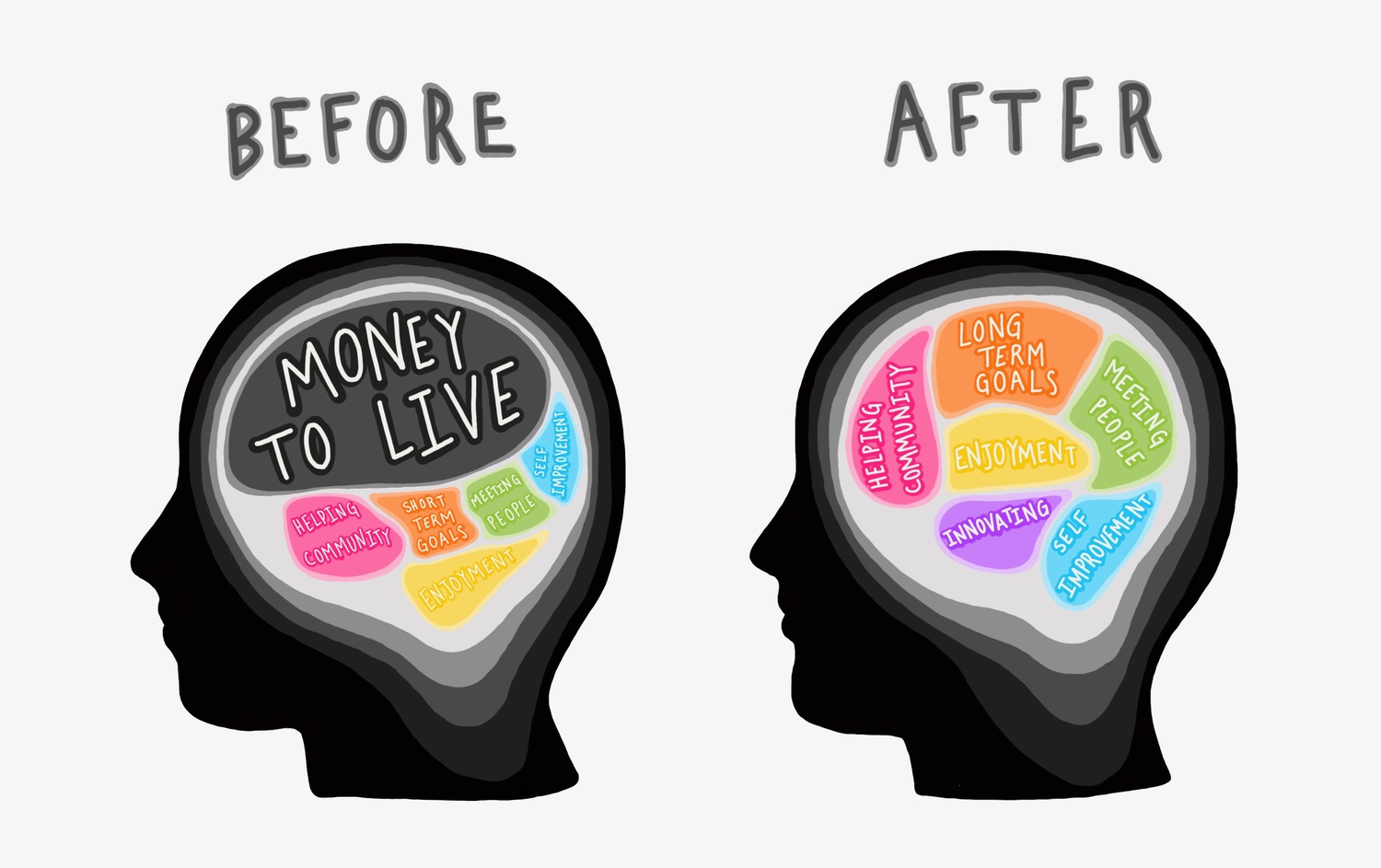

This is an example of the scarcity mindset: a mental shift due to the perception of scarce resources. Our brains have limited bandwidth, so any attention afforded to one immediate problem cannot be used somewhere else. The scarcity mindset is not always a bad thing; it was once an evolutionary advantage. When early humans lacked essential resources like food and shelter, this mindset helped them focus on acquiring what was most important. Even today, it can help us concentrate on tasks in the face of deadlines.

But the scarcity mindset makes escaping poverty extremely difficult. You can’t invest in the future when your present needs are not met. Limited money and extreme focus on the short-term make it hard to plan ahead. It’s having to repeatedly buy cheap pairs of boots versus buying one expensive pair that will last your whole life. While it makes sense at the time to buy daily necessities like food rather than pay bills, putting off those tasks ends up costing more in the long run when you have to pay late fees. People are not poor because they make bad decisions; people remain poor because poverty inhibits their ability to make good decisions.

The effects of poverty and scarcity go beyond just the brain. The link between poverty and poor health is well-established, and to guarantee adequate healthcare to all Americans, we have to fix the economic conditions that make them prone to sickness in the first place. Chronic stress, often the result of constant financial worries, puts millions of Americans at increased risk for a litany of preventable illnesses like heart disease, depression, weight gain, and more.

Furthermore, kids who grow up in poverty suffer from the consequences their entire lives. Child poverty can impact brain development, which may lead to mood disorders such as depression and substance abuse later in life. In the United States, children in poverty have lower standardized test scores, are more likely to drop out of school, and are less likely to go to college.

And there’s an important — but hard to measure — effect on our communities too. When we feel that money and goods are scarce, we start to think of our neighbors and fellow citizens as competitors rather than teammates united by our shared humanity. When we believe that the economy is zero-sum, we also come to believe that helping another person comes at our own expense. Helping our fellow humans escape poverty, debt, and misery becomes a disservice to the wealthy, rather than an expression of compassion and justice at the foundation of a society of equally free and valued people.

As I argued in my previous column, the U.S is more than capable of establishing a universal basic income — a monthly payment to all citizens sufficient to meet their basic needs. This proposal could virtually eliminate poverty overnight and start shifting our collective mindset from one of scarcity to one of abundance. We have more than enough food, water, shelter, and other goods to meet everyone’s basic needs. Scarcity is dead — technology killed it decades ago. The scarcity that remains is a result of poor allocation of resources, not a lack of resources.

A recent basic income trial in Ontario, Canada, despite being shut down less than halfway into its three-year run, offers a thrilling peek at what we can achieve by rejecting our societal scarcity mindset. A vast majority of participants reported improved physical and mental health. Many quit or reduced their use of tobacco and alcohol. Not to mention more exercise, better diets, better jobs — over a quarter enrolled in school or training programs, and nearly half of respondents said they volunteered more often. People were able to spend more time with friends and family and on activities they enjoyed outside of work.

We must understand that investing in people is never a waste — not only do we have the resources to provide for everyone, but also we will get far more out of it than we put in. When more people are encouraged to learn and go to school, we all gain from a more educated society. When we cure the stress that results from financial insecurity, we will all be healthier. When we give people the ability to choose the work they do, our economy will be more productive and we will all be freer. If we choose to base our society around mutual trust and cooperation rather than competition, we will all be happier and less stressed.

Basic income can shift our society from a mindset of scarcity to a mindset of abundance. It recognizes that we are all human beings with a right to existence. It says that all citizens have inherent value. It reminds us that we do not have to compete — that there is enough to go around. And it encourages us to cooperate, to trust, and to build up our fellow Americans. It’s time for a society of cooperation, not competition. It’s time for universal basic income.

Matthew B. Gilbert ’21 is a Computer Science concentrator in Adams House. His column appears on alternate Thursdays.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

Most Read

- Harvard Suspends Research Partnership With Birzeit University in the West Bank

- 2 Years After Affirmative Action Ruling, Harvard Admits Class of 2029 Without Releasing Data

- Give the Land Up — Or Shut Up

- More Than 600 Harvard Faculty Urge Governing Boards To Resist Demands From Trump

- Harvard Students Don’t Need To Work Harder. Administrators Do.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

With innovative financial tools combined with financial education, Collegiate empowers students to take control of their finances and build confidence in their money management skills.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

Admit Expert is a premium MBA admissions consulting company, helping candidates secure admission to top B-schools across the globe with significant scholarships.