News

When Professors Speak Out, Some Students Stay Quiet. Can Harvard Keep Everyone Talking?

News

Allston Residents, Elected Officials Ask for More Benefits from Harvard’s 10-Year Plan

News

Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin Warns of Federal Data Misuse at IOP Forum

News

Woman Rescued from Freezing Charles River, Transported to Hospital with Serious Injuries

News

Harvard Researchers Develop New Technology to Map Neural Connections

Hand-Washing in the Time of Coronavirus

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the importance of prices as a regulation of consumption in times when goods are in short supply. Back then, I was simply making the case that for markets, in which prices are allowed to rise naturally, individuals are much less likely to hoard scarce resources. Now, we’re actually seeing this type of hoarding in action — of everything from hand sanitizer to toilet paper to face masks, in places ranging from Georgia to France to Hong Kong. Even in our own backyard, the problem persists. When I visited CVS in Harvard Square Wednesday morning, they were out of both hand sanitizer and masks. Indeed, the seemingly irrational unwillingness of many sellers to raise prices of face masks has led to concerns that the doctors who need masks most may not be able to secure enough of them.

The coronavirus is, after all, one of those events that leaves us feeling a sense of almost complete powerlessness: a disease that is essentially an invisible enemy. Each day, CNN and the New York Times tell us about new appearances of the virus. In January, we knew it was in Asia, as cases migrated from China to Korea and Japan. Then it popped up in France and Italy. Suddenly Iran had it too. The international spread had begun. Now, health officials say that the United States is on the eve of an outbreak, and that this is almost certainly a pandemic.

So what should we really expect? Marc Lipsitch, a professor of epidemiology at the School of Public Health, is making projections that 40 to 70 percent of the world will be infected by the virus, given the length of the vaccine development process. The World Health Organization pegs the eventual fatality rate between 1 to 2 percent; the CDC says it may be lower than 1 percent. In a world of 7 billion, even if we take the most conservative estimates of these numbers, the back-of-the-envelope math generates a death toll well in the millions. Now, we could cast doubt on a Harvard epidemiology professor and say he should do some robustness checks on his model (for our own sanity), but then again, most of us can’t pretend to be epidemiologists ourselves. Humor me and let’s assume that these experts have a point; if they’re right, we could be facing a really seismic event unprecedented in our lifetimes.

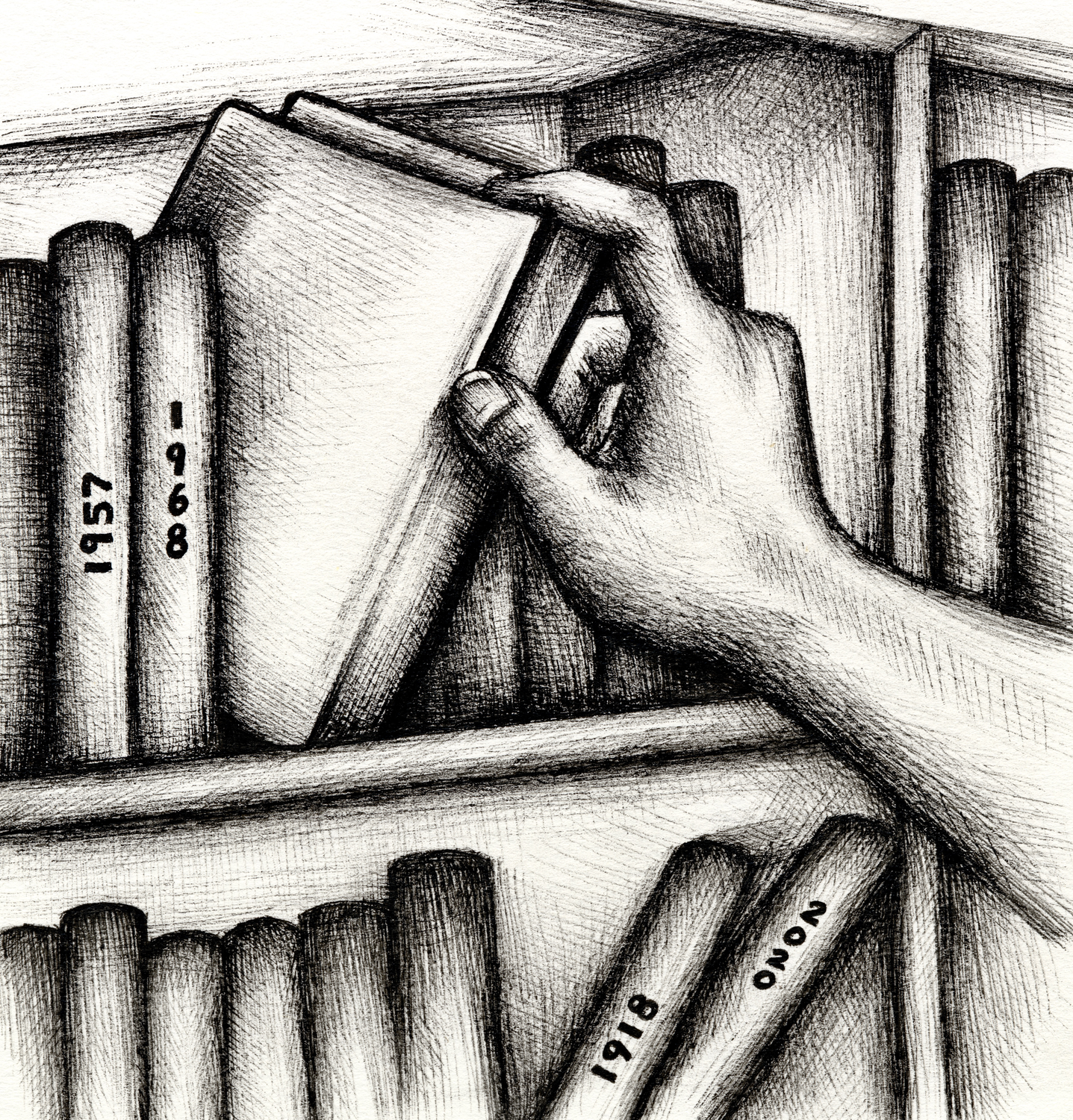

This brings me to the point. Most of us are pretty myopic when it comes to history; we tend to forget how recently the United States faced pandemics that actually inflicted damage on the scale of the worst-case projections for this virus. In 1957, the “Asian Flu” led to an estimated 1 to 2 million deaths worldwide, including more than 116,000 deaths in the United States. In 1968, the “Hong Kong flu” led to more than 100,000 American deaths.

I would wager that 99 percent of Harvard students have never heard of either outbreak. 1957 might bring to mind the Sputnik launch or the Little Rock Nine; 1968 is, in most of our minds, the year of Vietnam and the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy. Indeed, the Smithsonian’s summary of major American events of 1968 doesn’t even mention the flu that killed more Americans than the entire war in Vietnam.

Our natural response may be: “but surely we aren’t living in 1968 anymore.” How can health officials in the 21st century tell us that the only preventive measure at our disposal is washing our hands more carefully? We automatically expect medical advances to prevent deaths of this scale from happening today. Perhaps they will. Certainly, researchers are working around the clock on vaccines (for those who don’t get the virus first). But for cases of people who already have it, active quarantine measures appear to be the best way to slow its spread.

It’s poetic in a way — that some techniques of the 14th century still must be used today. In a world with space shuttles, self-driving cars and high-frequency trading, that’s the best we can do at the moment. This doesn’t mean we should accept mediocrity in the long run; that would be unacceptable in a field as important as public health. But you fight the war with the army you have, not with the army you wish to have. In any case, such situations demand from us a degree of humility, and serve as reminders that humans are still — partially — enslaved to fate.

In any case, the whole virus could blow over, so this article may not age well. But if it doesn’t go away, we may face an event of a magnitude that no longer exists in our collective memory and yet happened not so long ago. After all, history repeats when history itself is forgotten.

Andrew W. Liang ’21, a Crimson editorial editor, is a Social Studies concentrator in Adams House. His column appears on alternate Thursdays.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.