News

Harvard Grad Union Agrees To Bargain Without Ground Rules

News

Harvard Chabad Petitions to Change City Zoning Laws

News

Kestenbaum Files Opposition to Harvard’s Request for Documents

News

Harvard Agrees to a 1-Year $6 Million PILOT Agreement With the City of Cambridge

News

HUA Election Will Feature No Referenda or Survey Questions

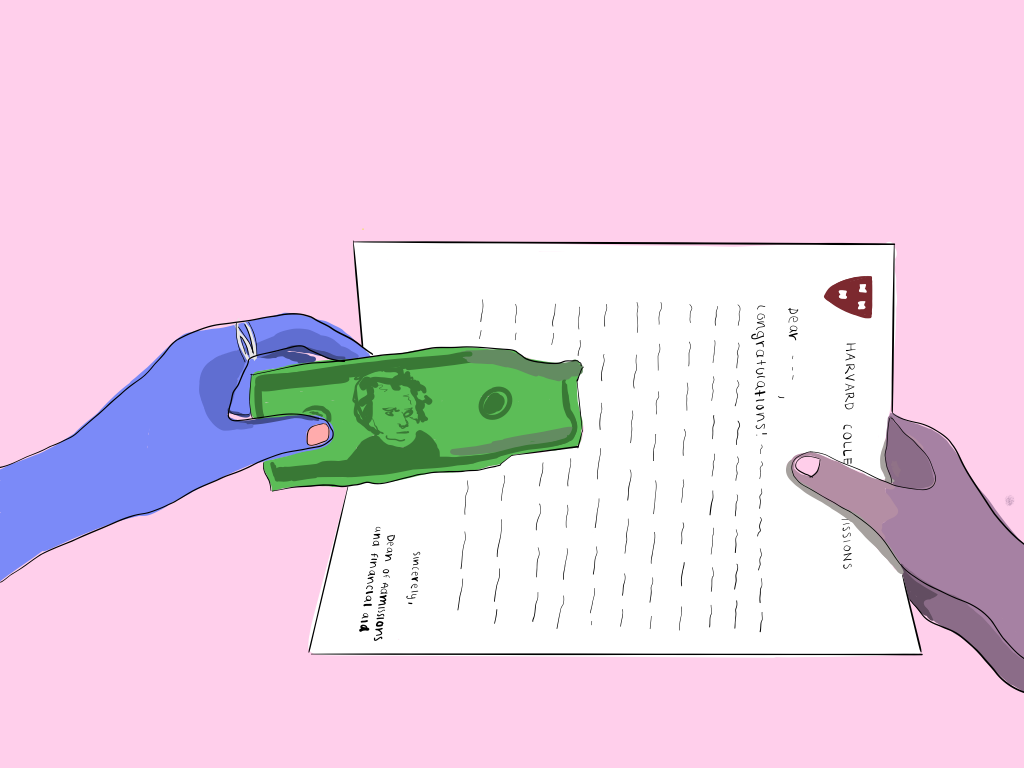

Should Harvard Admit More Rich Kids? Actually, No

Harvard’s own admissions website features a bold-faced lie: “There is no formula for gaining admission to Harvard.”

Then how can Harvard explain the Dean’s Interest List? Why are legacies given a bump? Why do children of faculty get special treatment? Perhaps I have different priorities, but none of these bear any relevance to a student’s proficiency.

While admitting the children of donors might have some financial benefits, this blatant preference is unjust and undermines both Harvard’s educational mission and its stated admissions policies.

The time has come for Harvard to make its admissions more meritocratic.

According to a recent op-ed, approximately 167 students from the Dean’s list are admitted each year. There are 1,647 students in the class of 2028. That would mean 10 percent of my class got in with preferential treatment.

Economist Peter S. Arcidiacono estimates that these special candidates, many of whom have relations to top donors, are privy to a 42 percent acceptance rate. That’s more than a couple points higher than the typical three percent figure you might see online. If we omit the 30 percent of Dean’s listers that could have gotten in based on their other qualifications, that leaves 117 acceptances.

That’s 117 rejections of qualified, hard-working applicants. 117 people who likely wouldn’t have gotten in without a check from dad in the mailbox. 117 people who benefit from America’s long history of socioeconomic immobility.

Harvard loses 117 students who should have gotten in the honest way — and that statistic does not account for advantages afforded to non-Dean’s list legacy, feeder school, or athletic advantages.

Dean’s listers already have eighteen years of privilege and extra opportunities. There are 21 feeder schools across the country known for their exorbitant Harvard acceptance rates. There are wildly-expensive college counseling and private SAT tutoring firms. There’s access to prestigious internships to bolster a Common App extracurricular list and the financial security to participate in expensive extracurriculars or study abroad, not to mention the extra free time from not having to work a job.

Dean’s listers already benefit from a whole host of advantages. Why give them another?

Perhaps threats of an endowment tax warrant attempts to protect donations. But current admissions policies shouldn’t be based on unrealistic, unenacted legislation.

The 118th Congress had three dozen Harvard graduates in the House. The Senate had 13 from Harvard and nine from Yale. Another seven senators have at least one degree from Georgetown. Do we really think a body filled with elite university graduates is going to approve a heavy-handed tax against their alma maters?

Some may argue that Harvard’s commitment to meeting demonstrated need is directly based on the generosity of its philanthropists. But in 2023, Harvard finished the fiscal year with an $186 million operating surplus. In 2022, the surplus was $406 million.

Current use gifts from 2023, totalling $486 million, fund only about 8 percent of operating revenues. This is no insignificant amount, but it is still in the ballpark of past surplus.

Despite enduring a 14 percent drop in overall donations, Harvard saw its endowment rise for the first time in years. Coupled with cushy operating surpluses, Harvard might have a future without pandering to high-profile donors after all.

Morally, putting the children of wealthy donors on a pedestal is a slap in the face to those more deserving. And financially, Harvard has the capital to withstand the coming storm — if it ever arrives.

As a former Boston Latin School student, I’ve seen the advantage such privilege confers firsthand. Trust me, we don’t need a Dean’s list to perpetuate it.

Katie H. Martin ’28, a Crimson Editorial editor, lives in Wigglesworth Hall.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.