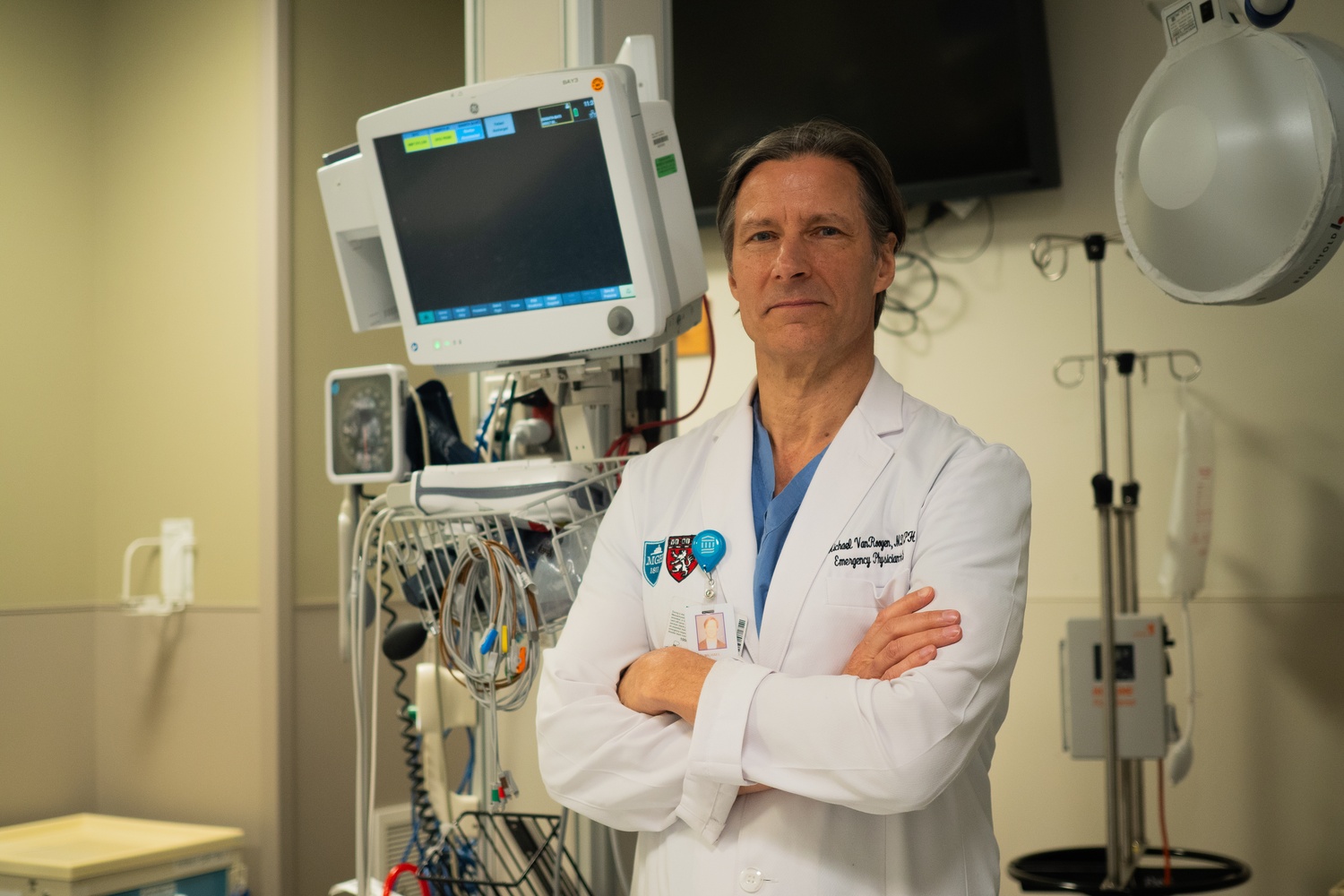

In the Eye of the Storm

The first time Michael J. VanRooyen needed to remain calm under intense pressure, he failed. And the second time. And the third time.

Terrified of his Boy Scout instructor — the town’s Chief of Police — the teenage VanRooyen flunked his First Aid Merit Badge assessment three times before finally earning the honor. After that experience, VanRooyen was determined to never fall apart again during an emergency — a promise he fulfilled during 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Democratic Republic of Congo, in Ukraine and Palestine.

VanRooyen, though, did not plan on a life of dispatches to terrorist attacks, natural disasters, and war zones. At a young age, his mother’s cancer diagnosis led to long hours in the hospital. He felt “drawn to medicine,” and aspired to be an emergency physician.

In 1992, less than a year after finishing residency, VanRooyen traveled to Somalia to screen children for malnutrition and scabies in a refugee camp outside Mogadishu. Among the children lined up to get screened was a malnourished girl, around five years old, who needed to be hospitalized immediately. When VanRooyen asked the women at the camp who her mother was, they responded that no one took care of her.

“I was indignant,” VanRooyen says. “How can it possibly be that there’s a young girl who is standing there malnourished and not being taken care of?”

Then, one of the women in the camp grabbed him by the sleeve of his scrubs, and without saying anything, took him to her tiny makeshift tent, where two children sat among pots and pans. VanRooyen suddenly realized that the woman had no choice but to care for her own children and leave the little girl to die.

“I felt really ashamed,” he says. “Not just embarrassed, but ashamed, because I didn’t really understand the context.”

That day, VanRooyen vowed that he would never be the “white savior humanitarian” and to instead reevaluate and improve the humanitarian field. Now, much of VanRooyen’s work revolves around crafting a “more informed, more sensitive, more educated, more evidence-based, and more professional” pathway for humanitarian workers.

While continuing to work on the ground during humanitarian emergencies and see patients as an emergency medicine physician for the past three decades, VanRooyen created the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, which includes a “humanitarian academy” to train future workers in the field and a research branch to drive more evidence-based humanitarian policies.

VanRooyen’s mentorship in the humanitarian field begins with young students. He teaches GHHP 70: “Humanitarian Response to Conflict and Disasters,” an undergraduate course that culminates in a multi-day humanitarian crisis simulation in the Harold Parker State Forest. The students role-play different teams from non-government organizations. They camp, eat MRE rations, and negotiate humanitarian aid.

For VanRooyen, there are many parallels among the hats he wears as an emergency physician and leader in humanitarian aid. VanRooyen views humanitarian workers as the doctors for nations: when a person gets hit by a car, they turn to an emergency room physician. When a country is hit by a natural disaster, they turn to humanitarian aid. In his eponymous book, he calls humanitarian aid “the world’s emergency room.”

For VanRooyen, “getting ready to respond to an emergency, building capacity to respond to an emergency, and educating leaders so that they can better respond to emergencies” are the goals that guide his life.

Now, VanRooyen is gearing up to face a new kind of crisis — the recent “destruction” of the U.S. Agency for International Development, which contributes more than 40 billion dollars in foreign aid annually. With this funding taken away, VanRooyen poses a question: how should the humanitarian sector determine what efforts to preserve and what efforts to cut?

“Global humanitarian aid is going to have to radically change what it does,” VanRooyen said. However, his outlook for the future remains hopeful.

“It is going to take a new approach, innovation and advocacy, and further doubling down on our mission of evidence-based practice and professional development — that is what we are going to do,” he said.

—Magazine writer Nora Y. Sun can be reached at nora.sun@thecrimson.com.