On Digis and Dispos

We’ve all seen it: It’s the week after finals, and you open Instagram to find a flood of semester photo dumps from your classmates. Among these is often a classic group picture taken at a formal or party where everyone is adorned in dresses and ties, cheesing at the camera, their pearly grins reflecting the flash — and sure enough, a yellow timestamp dots the corner of the photo.

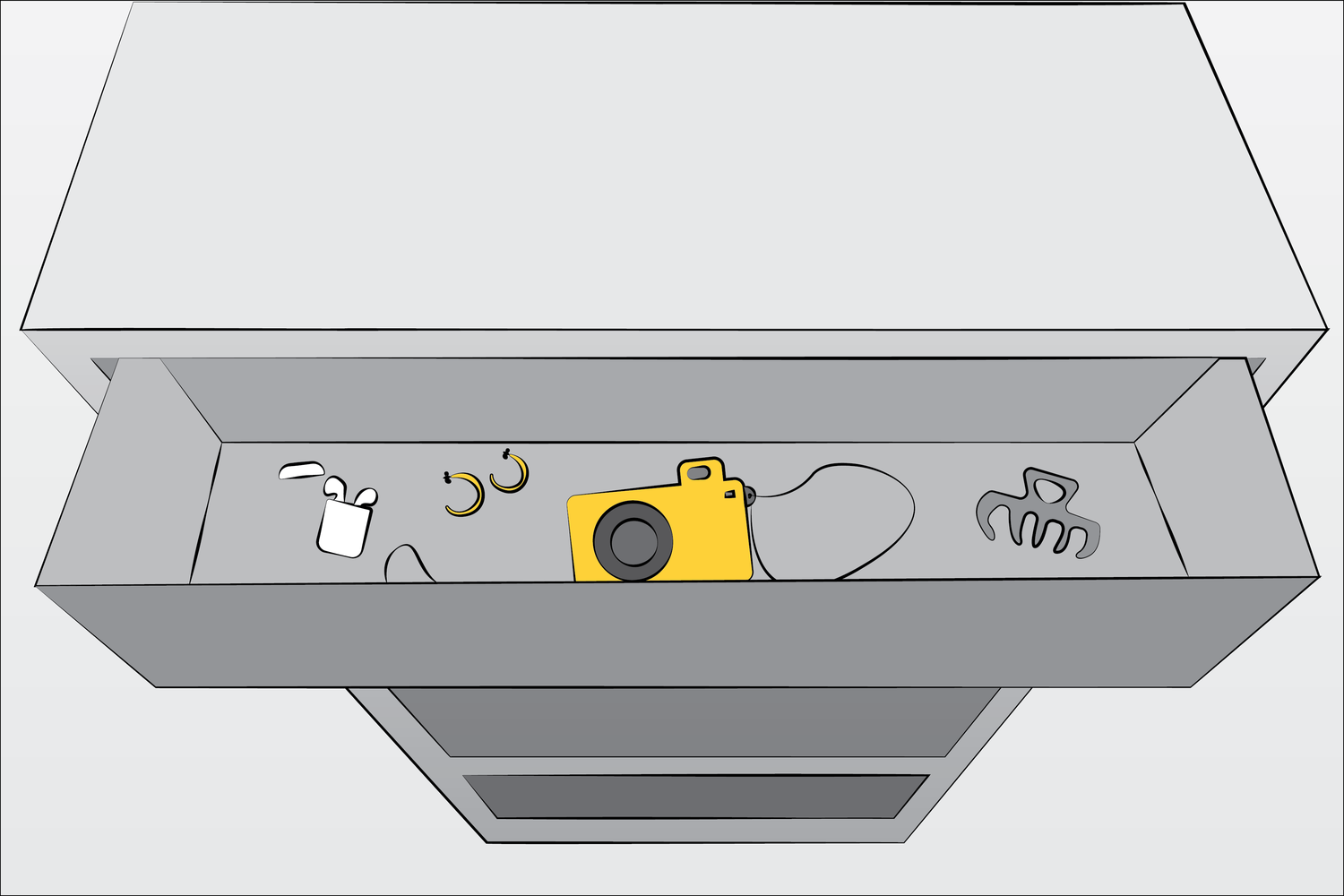

Digital and disposable camera pictures have become something of a status marker among college students. In some cases, they might be an indication of wealth among students who are able to go out of their way to buy a roughly $50 device for a feature their cellphones are already equipped with. Owning these specialized cameras also suggests that these people are secure in their social lives, in that there will indeed be several opportunities for them to snap pictures — their purchase is thus considered an investment for their friend group, a pledge to continue creating and savoring memories.

But even beyond these measures, the effect of these photos on our generation must be considered in their context of being uploaded to social media, as this is certainly not the original purpose of these cameras. Gen Z has adopted and reclaimed more analog modes of capturing moments, perhaps as a way of grounding and slowing down in today’s high-tech, digital-first, AI-powered whirlwind. The appeal of these devices, then, is that they’re viewed as more classy, timeless, and therefore “elevated” forms of taking pictures than the merely convenient functions offered by smartphones. Yet, when the pictures are uploaded to Instagram — which is meant to be an accessible, standardized platform — to be seen on the same feed as smartphone photos, there’s an inherent air of superiority they may convey, in light of comparison.

It’s not always necessarily the case that photos taken on cameras are even higher quality. Disposable cameras, as implied by their name, are limited in their use as well as their settings, with limited room to adjust lighting and hues. Once developed, the pictures also tend to appear dim and grainy. Yet, it might actually be this reduction and simplification of photos that make these cameras appealing: They offer a form through which we can simultaneously preserve moments and varnish them, so that even mundane experiences can be captured to exude more warmth and luster.

So the assumptions we might make when encountering disposable or digital pictures on social media are possibly more rooted in the story we assign its characters: The person taking the photo, the owner of the camera and perhaps “photographer of the group” is someone who is committed to their use of analog devices and attempting to truly “living in the moment,” while their subjects excitedly encourage this curation, unabashedly posing, hoping they look their best, and awaiting receipt of the photos in anywhere from a week to several months, depending on the disposable variety. Either to be real or to show off, or some combination of the two, some photo dumps will even include a playful picture of the photographer with their eye to the camera itself, about to shoot — pridefully, literally flashing their craft.

Is the insistence on using these devices performative? Or is it an attempt to savor the moment and enjoy the little things in such a fast-paced world?

A recent NPR episode of “All Things Considered” on the return of the digital camera among Gen Z suggested that the revival was sparked by nostalgia for the early 2000s and a resurgence of vintage style. Yet, it also mentioned its association today with achieving a “trendy influencer look.” Undoubtedly, in today’s age, we must admit that the way we capture and share pictures is no longer just a matter of preference or preserving tradition, but a deliberate choice to shape how we are perceived by others.

While there might be a level of pretension implied by digital camera photos, as something more sophisticated and unlike the rest of the photos on our feed, their relevance among Gen Z is ultimately attributed to their virality on the very platforms they are being uploaded to. It’s possible that this is inherently subversive to the “authenticity” these forms are originally associated with, that which Gen Z strives for.

Just as Instagram was technically intended to make photo sharing effective from our smartphones, digital and disposable cameras were not designed with mass-distribution in mind — to be seen by an audience outside of your close circle, or even duplicable. The fact that Gen Z nevertheless combines these two forms, seemingly at odds with each other, perhaps shows we’ve invented a new form of photo sharing entirely. Ultimately, it proves we are willing to forgo convenience for aesthetics, either that of the photography experience itself, or of our feeds.

Whatever the benefit, we seem to get the best of both worlds. We’re afforded the enjoyment of opting to take pictures with specialized cameras as a way to “unplug” and be present in the moment, but also later, when we want to “reconnect,” to easily post the ravishing images for followers to see.

Aesthetics are our generation’s weakness. This camera phenomenon might just reveal our compulsion to romanticize more moments of our lives than necessary, and to make it publicly known. Now, maybe it’s time for us to step back and ask: Are we capturing memories, or are we simply curating them for the feed?

Sometimes, the photos we take matter less than the moments we’re truly present for.

—Associate Magazine Editor Chelsie Lim can be reached at chelsie.lim@thecrimson.com. Her column “Form Fitting” explores the social and physical structures by which we are contained, reconciling how their literal and metaphorical forms manifest into our experiences of them.