News

News Flash: Memory Shop and Anime Zakka to Open in Harvard Square

News

Harvard Researchers Develop AI-Driven Framework To Study Social Interactions, A Step Forward for Autism Research

News

Harvard Innovation Labs Announces 25 President’s Innovation Challenge Finalists

News

Graduate Student Council To Vote on Meeting Attendance Policy

News

Pop Hits and Politics: At Yardfest, Students Dance to Bedingfield and a Student Band Condemns Trump

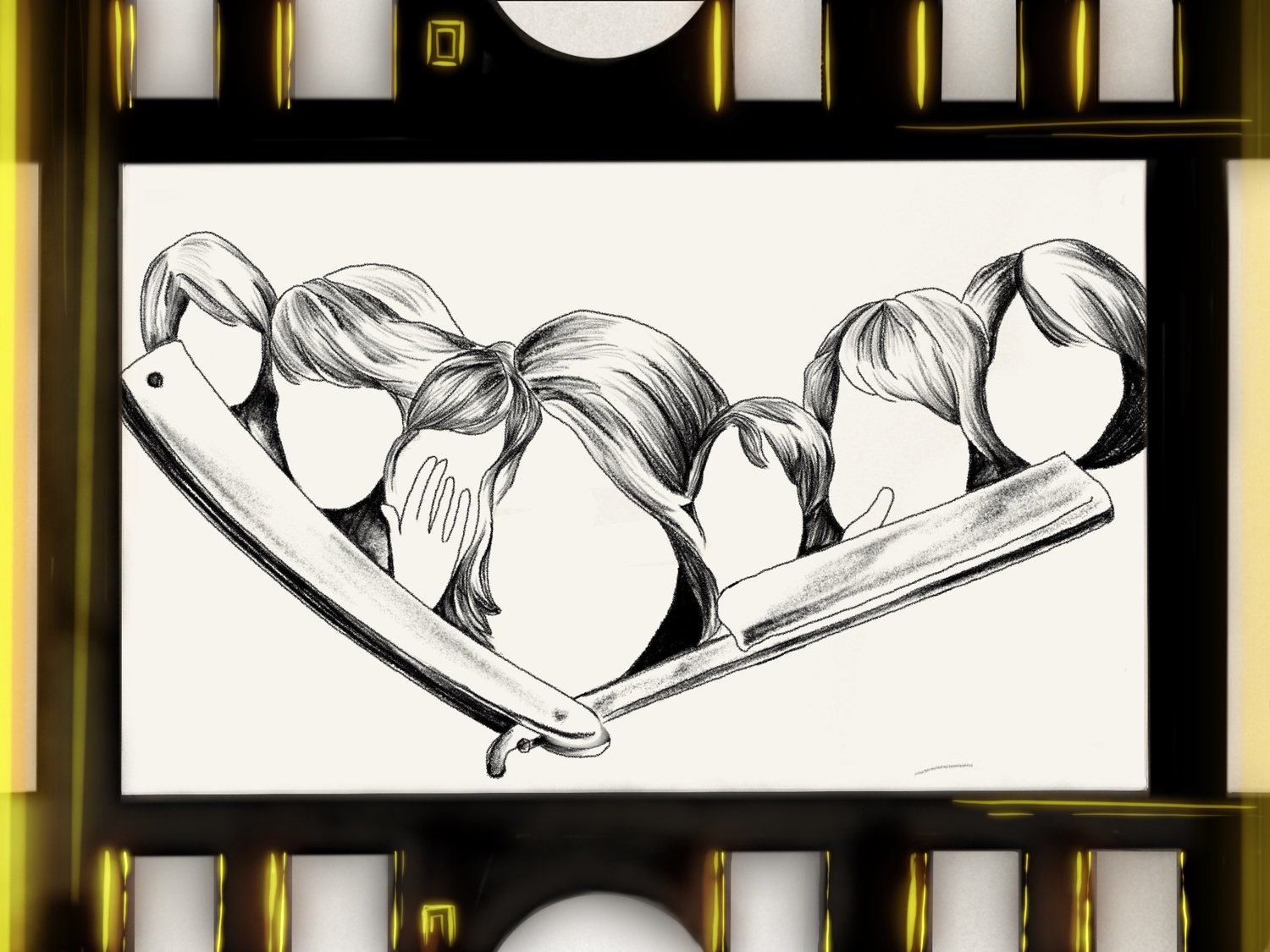

Revisiting ‘Repulsion’ 60 Years Later Amid Polanski’s Criminal Charges

“Repulsion,” the 1965 horror film starring Catherine Deneuve, screened on Feb. 7 as part of a double feature at Harvard Square’s Brattle Theatre.

The plot centers around a young French woman, Carol Ledoux (Deneuve), who lives in London with her older sister and works as a manicurist. Carol’s character is defined by her acute shyness and repulsion toward the men in her life. She dreads intimacy and yet at times seems intrigued by the prospect of it. The audience witnesses moments of tentative curiosity involving desire and sexuality, highlighting her complex and contradictory relationship with attraction.

When Carol’s sister leaves to accompany her boyfriend on a trip to Italy, Carol — alone in their apartment — begins to descend into a kind of mania, characterized by nightmares and hallucinations. She becomes increasingly reclusive and terror-stricken, eating little and remaining hidden in her apartment, consumed by both mirages and realities of violence, rot, and destruction.

Carol’s anxiety is apparent from the opening scenes of the film — her discomfort with men, including her sister’s boyfriend, only becomes more acute over time. The film is a brilliant horror, the majority of which takes place within Carol’s apartment. Deneuve is incredible in the role, convincingly playing a woman whose fear is palpable and potent. Her fear even warps the viewer’s sense of time, immersing the audience in Carol’s distorted reality.

Repulsion is ultimately a film that explores what happens when fear of violation mingles with mental illness. It’s a horror film whose terrors are undeniably real and whose themes of brutality, harassment, and sexual violence have new implications in light of Roman Polanski’s history of sexual assault.

In 1978, Polanski fled the U.S. as a fugitive after pleading guilty to unlawful sexual intercourse with a minor.

“Repulsion” was the French and Polish director’s first English-language film, shot in the United Kingdom. In 1968, upon Polanski’s move to the United States, he went on to direct some of his more well-known films, including “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968), “Chinatown” (1974), and “The Pianist” (2002). All were met with acclaim, being nominated for and winning prestigious awards from various organizations in various categories. Despite his status as a fugitive, Polanski continues to create films outside of the U.S., and the impact of his work has been long-lasting. “Repulsion” is among said films that are revered for their artistry and detail.

The film plays with sound and light, at times amplifying them to an almost uncomfortable degree, only to later reduce them to imperceptible levels. The film’s success rests upon its purposeful depiction of its protagonist and uncanny ability to contort time and space.

Diverse cinematography defines “Repulsion.” Close-up shots, first-person perspectives, and panning across scenery convey Carol’s claustrophobia while never allowing audiences to truly feel acclimated to the setting. Long scenes feature her mumbling to herself, snacking on sugar cubes, and lying in bed. These calm and quiet moments brutally juxtapose the more violent elements of her seclusion, including her hellish visions in which hands burst through the walls and paw at her or large cracks appear in the walls. It’s as if her apartment is being destroyed from the inside out. Despite the effects’ simplicity when compared to CGI and the prop potential of films today, the horror she endures is no less traumatic and jarring for its lack of technology.

The score emphasizes the realness of her fear by featuring repetitive bells, cymbals, and other forms of percussion that swell to a crescendo in moments of terror. Conversely, the film goes completely silent, forcing viewers to witness the horror of her nightmares — denying them a respite from the violence.

Although the film is at times slow, it remains incredibly well done, containing interesting dialogue, strong acting, and a creative plot. Part of what makes the film so haunting is the realness of Carol’s nightmares. The potential of sexual violence isn’t minute; her hallucinations exist not only in her mind but in the world outside of her apartment. In this way, the film encourages the audience to empathize with Deneuve. The story is not simply one of mental illness but one in which a complex and plagued woman fractures because of threats both real and perceived.

In terms of widespread dialogue about the quality and value of “Repulsion” as a film, there isn’t much dissent as many critics acknowledge the film’s general success as a piece of media. In the wake of Polanski’s guilty plea, the conversation has shifted to whether and how audiences should reassess the film, knowing it was created by someone accused of sexual assault in multiple lawsuits.

Samantha Geimer, one of his victims, published an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times in 2003, titled “Judge the Movie, Not the Man,” writing, “Mr. Polanski and his film should be honored according to the quality of the work.”

While Geimer believes that films should be judged on merit alone, there are dissenting opinions.

Actor Asia Argento — who accused Harvey Weinstein of sexual assault — was asked in a 2018 interview with The Guardian how she feels about Polanski still being celebrated as a director.

“It’s shocking that people like Polanski are still revered, celebrated by actors and fellow film-makers and cinematheques around the world who continue to not only promote their work, but also to work with them,” Argento said.

The varying perspectives elicit questions about what accountability looks like for people in the public sphere and about whose responsibility it is to dole out the consequences. It brings up the age-old question: Is it fair to separate the art from the artist?

What makes this debate particularly relevant in the case of “Repulsion” are the similarities between the nature of Polanski’s crime and the film’s themes. “Repulsion” explores the concepts of sex, relationships, and violence but from a distinctly female perspective. It’s shockingly empathetic in its portrayal. It’s a story of mental health, yes, but also one that details the intricacies of fear and desire, curiosity and violence. The film doesn’t derogate or ridicule; It skillfully avoids portraying Deneuve as a victim of “female hysteria” and instead realizes her fears. It implicitly speaks to the prevalence of sexual and physical violation — not only in its most explicit forms but also as violations of spatial and physical boundaries.

In the case of “Repulsion,” these questions are even more relevant considering the scary yet empathetic nature of the film.

In sum, this film offers a nuanced illustration of sexual desire and fear. Looking at it with the context of Polanski’s crime and filmography in mind, one has to question the cost of this kind of representation and whether its impact outweighs its history.

—Staff writer Leah M. Maathey can be reached at leah.maathey@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

Where you should have gotten your protein since 1998.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

HUSL seeks to create and empower a community of students who are seeking pathways into the Sports Business Industry.