News

When Professors Speak Out, Some Students Stay Quiet. Can Harvard Keep Everyone Talking?

News

Allston Residents, Elected Officials Ask for More Benefits from Harvard’s 10-Year Plan

News

Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin Warns of Federal Data Misuse at IOP Forum

News

Woman Rescued from Freezing Charles River, Transported to Hospital with Serious Injuries

News

Harvard Researchers Develop New Technology to Map Neural Connections

From Sundance: 'Zodiac Killer Project' is a Witty Meta-Documentary That is Overly Self-Indulgent

Dir. Charlie Shackleton — 2.5 Stars

In 2012, an autobiographical novel by Lyndon Lafferty titled “The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up: The Silenced Badge” was published.

Lafferty was a regular highway patrol agent until one day, a strange encounter in a parking lot led him to fanatically investigate a man named George Russell Tucker — a man he believed was the infamous Zodiac Killer.

“Zodiac Killer Project” was intended to be a true crime documentary by Charlie Shackleton that adapted Lafferty’s novel. Shackleton was deep in pre-production when, suddenly and without explanation, the Lafferty family withheld the rights to the novel.

Thus, this film was born.

The title of Shackleton’s experimental documentary seems tenaciously banal, which feeds into the withheld, critical approach of the film’s concept.

“Zodiac Killer Project” is a documentary about a failed documentary — serving as both a cathartic reflection on Shackleton’s lost project and a critique of the indexical sensationalism of true crime documentaries.

Such grief for a film that never was results in a film largely composed of static shots or snail-pace zooms, pans, and car-mounted footage of the San Francisco Bay Area, where the ghosts of Lafferty’s story linger. Xenia Patricia’s quiet visuals of sun-soaked roads and places create a mitigating ambiance, drawing the audience’s attention entirely to Shackleton’s voice.

Shackleton’s narration, directed by dense bullet points, swims out of the film’s speakers with casual ease and improvisation. This is a firmly ant-sensationalist documentary that is, on paper, refreshing for “a genre at saturation point,” according to Sudeep Sharma of the Sundance Film Festival. It is a shame the film suffers from a painfully formulaic structure and hypocritical philosophy.

Each sequence in “Zodiac Killer Project” progresses as follows: A quotidian shot of a location where the original documentary would have been filmed, Shackleton explaining how he would have shot the sequence, a zoom-in as Shackleton indulges in a relevant quote from Lafferty’s novel, a commentary on a pervasive technique in true-crime filmmaking, a couple jokes, and a zoom-out accompanied by more narration.

Repeat.

This formula could have succeeded if the content of Shackleton’s lost documentary and the breadth of his commentary truly wanted to upend the true-crime genre. Disappointingly, the approach Shackleton envisioned for his documentary would have resulted in just another addition to the saturated market.

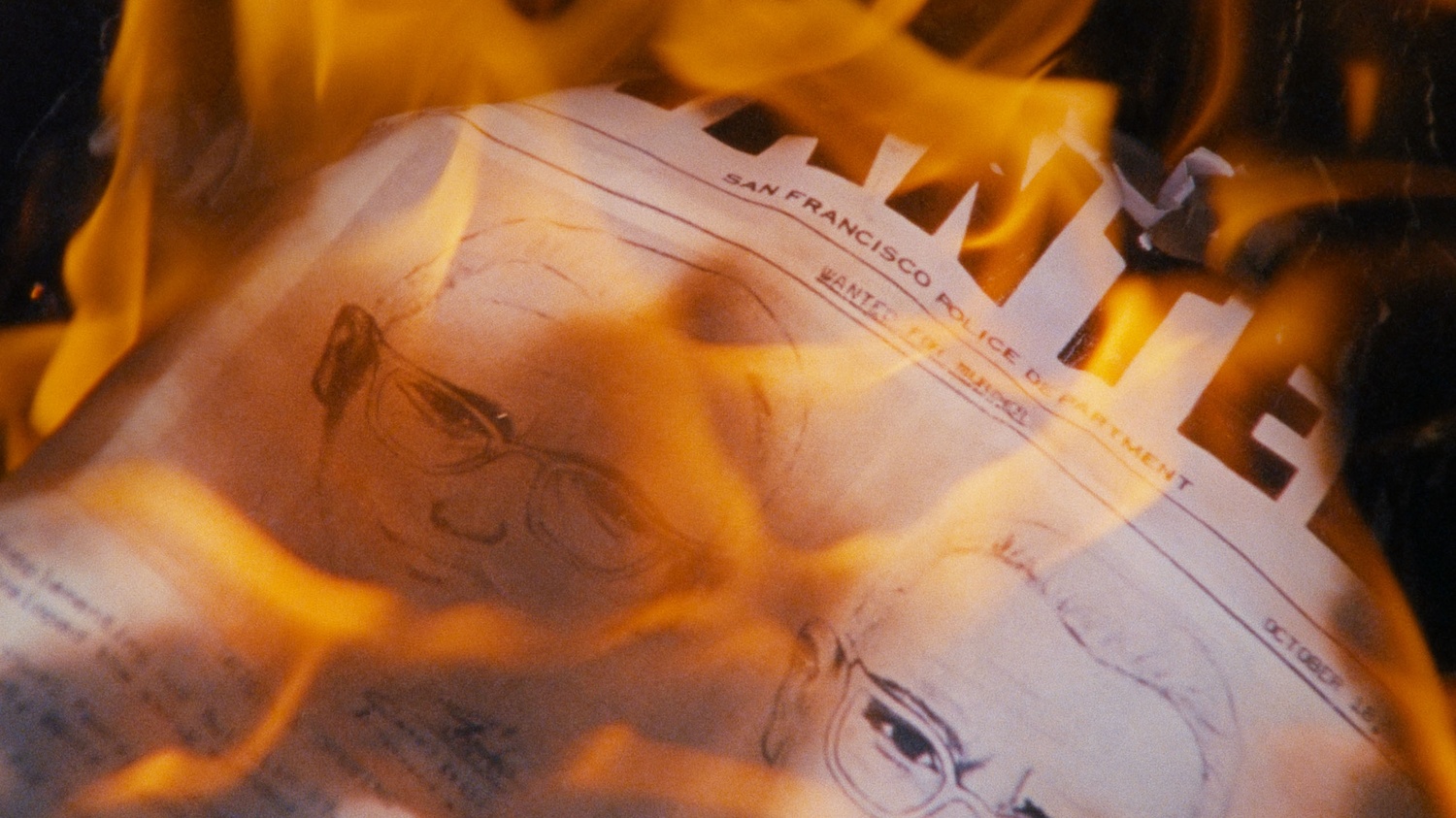

Shackleton uses the term “evocative b-roll” to describe the semiotics of the vague true crime imagery — dark silhouettes, burning cigarettes, swaying interrogation lamps — techniques commonly used to construct the genre’s aesthetic. He critiques these as indexical references that artificially further a documentary, yet — ironically and not in a clever way — this own lost film was poised to drown in them.

He actively jokes about falsifying locations — for example, not shooting at Tucker’s original house but a house that simply looks creepier — and exaggerating moments of Lafferty’s pursuit. These methods remain open to critique, even if the documentary never technically executes them. In Shackleton’s defense, everything only exists in narration.

The scenes that break away from the formula to deliver succinct commentaries on the true-crime genre are interesting but so sporadic that they add little to the film’s overarching intentions.

Shackleton’s research spans topics such as the homogenous intros of true-crime documentaries, the ethics of investigation in “The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst,” the increasingly hollow dramatics of “Making a Murderer,” and the demand for fictional macabre that often insensitively forgets the victims behind these tales — particularly in controversial series such as the first season of “Monster.”

All of these cutaways are temporarily engaging, but their structure and inclusion feel like YouTube video essays stitched into the documentary as an afterthought. The cutaways turn ethically dubious because Shackleton desires to partake in the very techniques he critiques.

There is an elusive shield that Shackleton believes sets his documentary apart — that by engaging in the expected techniques of the genre through a retrospective frame and pursuing an “authentic” aesthetic, he is somehow exempt from its pitfalls. Yet, this approach only ensnares him further, forcing him to concede that he cannot escape the genre’s ingrained schematics.

But this self-awareness ultimately works to Shackleton’s detriment. His analysis and execution never reach a level of complexity or intentionality sufficient to justify such a metacommentary.

It also doesn’t help that Lafferty’s intense suspicions about Tucker as the Zodiac Killer aren’t even the central subject of the novel. One look at the book’s blurb makes it evident that Lafferty actually attributes the killings to a network of government officials and police officers. These claims, however, were legally barred from inclusion in Shackleton’s documentary, further weakening its meta-concept.

“Zodiac Killer Project” is undoubtedly original in its presentation and concept, with a few standout scenes that benefit from the substance of Lafferty’s novel. Yet, with such a lack of self-awareness, Shackleton traps himself in the very indexicality he sets out to critique, leaving the documentary as little more than a witty director toying with surface-level what-ifs.

—Staff writer Kai C. W. Lewis can be reached at kai.lewis@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.