News

Nearly 200 Harvard Affiliates Rally on Widener Steps To Protest Arrest of Columbia Student

News

CPS Will Increase Staffing At Schools Receiving Kennedy-Longfellow Students

News

‘Feels Like Christmas’: Freshmen Revel in Annual Housing Day Festivities

News

Susan Wolf Delivers 2025 Mala Soloman Kamm Lecture in Ethics

News

Harvard Law School Students Pass Referendum Urging University To Divest From Israel

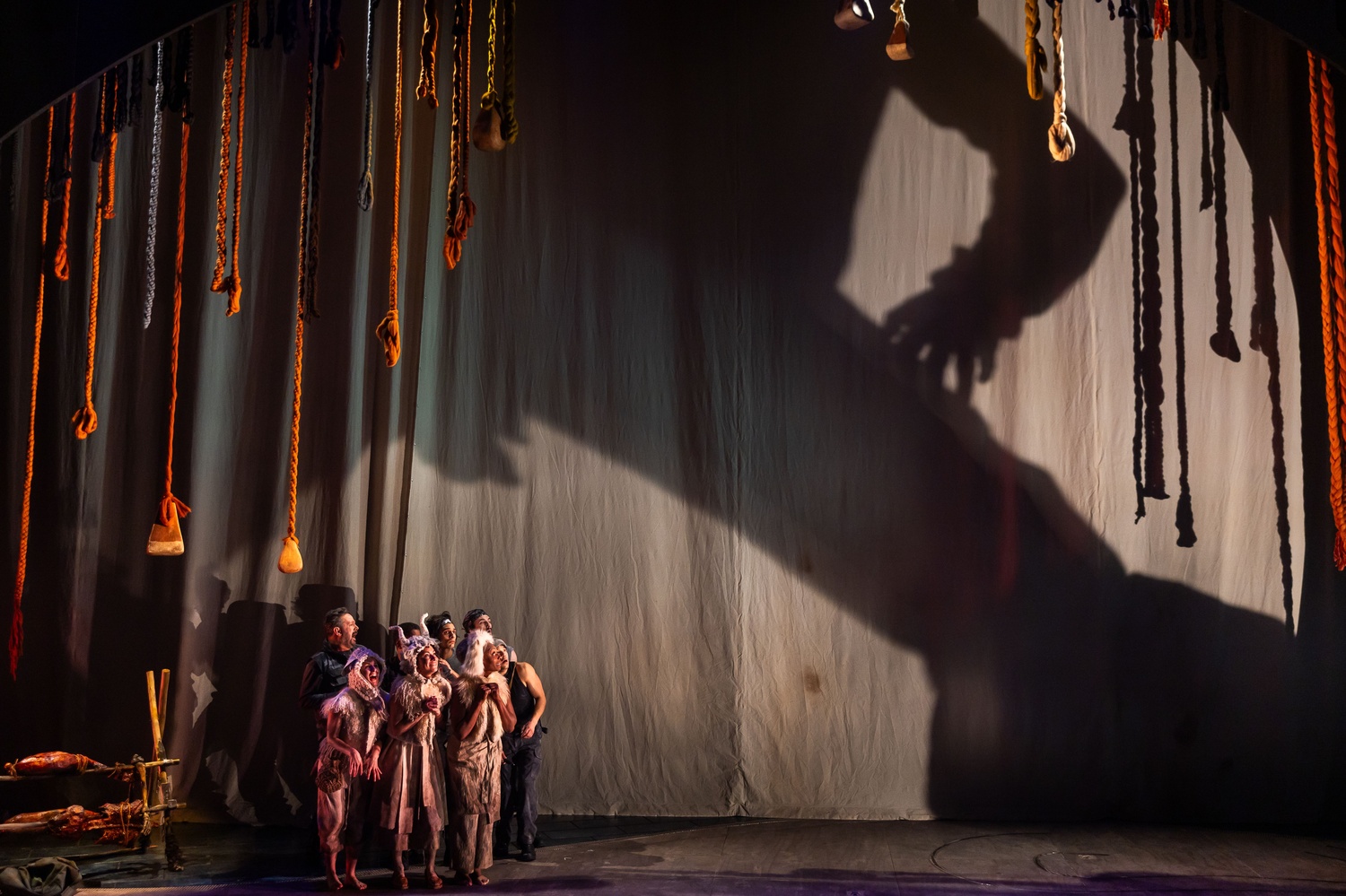

‘The Odyssey’ Review: An Unraveling of an Epic Tale

From the moment audiences enter the house of the American Repertory Theater’s Loeb Proscenium to see “The Odyssey,” they are transported to Ithaca, the home to the play’s protagonists, Penelope (Andrus Nichols) and Odysseus (Wayne T. Carr). A bronze bowl rests, faintly lit, at the center of the stage. With this centerpiece, framed by a proscenium arch adorned with ropes of varying lengths and accompanied by a soundscape of crashing waves, the stage begins to tell the story of Odysseus’s return to Ithaca and his wife’s struggles to fend off power-hungry suitors, before any character is introduced.

This dynamism is the central thesis of the play. When Odysseus enters the stage, he immediately begins washing himself — as dusty and dirty as the stage floor — with water from the bowl. Before words are spoken, the world on the stage is made real through the tactility of the props. Carr is not afraid to be messy, water splashes onto his clothes and the floor so that the scene flows from and within every surface of the stage.

Alongside Odysseus, are the three unnamed Fates — played by Alejandra Escalente, playwright Kate Hamill, and Nike Imoru. Acting as Odysseus’s living conscience, they narrate Odysseus’s past and give context to the present that the audiences now find themselves thrust into. In a unique contrast between interiority and exteriority, they also portray Penelope’s handmaidens who bear witness to her externalized moral struggles as she tries to stay loyal to her husband.

Just as the Fates move between roles, each transition seamlessly weaves each scene together like one of the featured tapestries Penelope makes in “The Odyssey.” With natural blocking by director Shana Cooper, transitions make full use of the stage — preceding scenes are inconspicuously contained in one half of the stage while a new scene begins in the other. In one notable moment, the Fates suddenly bleat like sheep, triggering a scene transition to Odysseus and his men on the evil cyclops Polyphemus’s (Jason O’Connell) island where the women now portray Polyphemus’s prized flock.

The creative team of “The Odyssey” demonstrate that they are ready to command all of the audience’s senses. Light and sound evoke the presence of Ancient Greek gods on the stage and amidst the audience, as evidenced by the sound of a large exhale and dimming lights when Odysseus and his men enter Polyphemus’s cave. The subtle nod to invisible characters controlling the fates of the ones the audience can see makes the world on the stage feel more rich.

While named “The Odyssey” after Homer’s iconic epic poem, the play does more than focus on Odysseus. Penelope is introduced in the first full scene of the play — a major shift from Penelope’s lesser role in Homer’s original poem and indicative of playwright Kate Hamill’s efforts to re-imagine this story with a feminist lens. However, Nichol’s portrayal of Penelope lacks the dynamic complexity her revitalized character demands. Her line delivery falls flat and lacks the dynamic nuance — Penelope’s mood is monotonously morose and mismatched with the intertwined themes of resilience and yearning that her character is meant to represent.

However, mixed media elements of “The Odyssey” rescue potential moments of stagnation. The actors became a part of the cloth, rope, wood, and string motifs of Sibyl Wickersheimer’s scenic design as they supplement expository monologues with shadow puppetry meant to represent Penelope’s weaving. Throughout the play, shadow puppetry is utilized to interpret the character of the cyclops Polyphemus and convey the story of Odysseus’s brutal attack on Troy.

Ithaca is represented by a neutral-colored asymmetrical set, but designer An-Lin Dauber’s costumes bring each individual to the forefront of each scene, emphasizing Hamill's efforts to break each character out of the story that audiences think they know. Male characters dress in dark modern clothing such as dark jeans and combat boots — with Odysseus’s soldiers occasionally sporting Cold War-era gas masks and combat helmets — and female characters wear brighter colors such as the Fates’ neutral off-white robes that match the set’s muted palette.

This contrast in costumes establishes the women in the play as scene creators and the men in the play as story disruptors. Penelope’s suitors, in particular, are dressed in gaudy fur coats, colorful beanies, headbands, and sunglasses in jarring “frat-bro” caricatures. These costumes alongside the anachronistic characterization of the suitors as young, vulgar drunkards slightly undermine the play’s gravity, but can be understood as an attempt to add familiarity and humor to the play for audience members who may feel detached from the play’s ancient origins — true to Hamill’s vision of the original classic’s “potential to speak to the times in which we live.”

Humor plays a role in mellowing villainous characters beyond the suitors in “The Odyssey.” The cyclops Polyphemus is a buffonish but sympathetic oaf, and the witch Circe (Kate Hamill) is silly and child-like despite paralleling Odysseus’s dark side. These flattened character portrayals are shallowly reimagined, but serve to highlight Odysseus’s austerity and allow the audience to consider his acts of violence and ask whether he is the true villain. The play’s humor begins to unravel the Odyssey’s traditional hero narrative, but occasionally seems awkwardly out of place. Instead of serving to build the story, actors mooing like cows and frequently over-emphasized profanity often distract from moments of poignancy.

Hamill’s play asks the essential question “If you’ve gone through something traumatic, can you ever go back to who you were?” It also challenges audiences to hold themselves accountable for their contributions to the romanticization of the violent actions of heroes. By the end of the play, when the water motif comes full circle and the lights come down on Penelope and Odysseus washing each other of blood, The A.R.T’s “The Odyssey” has unraveled and re-spun a moving tale that questions whether violence is ever justified and asks us all to reconsider the stories we celebrate.

“The Odyssey” runs at the Loeb Drama Center until March 16.

— Staff Writer Selorna A. Ackuayi can be reached at selorna.ackuayi@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

Most Read

- Harvard Suspends Research Partnership With Birzeit University in the West Bank

- 2 Years After Affirmative Action Ruling, Harvard Admits Class of 2029 Without Releasing Data

- Give the Land Up — Or Shut Up

- More Than 600 Harvard Faculty Urge Governing Boards To Resist Demands From Trump

- Harvard Students Don’t Need To Work Harder. Administrators Do.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

With innovative financial tools combined with financial education, Collegiate empowers students to take control of their finances and build confidence in their money management skills.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

Admit Expert is a premium MBA admissions consulting company, helping candidates secure admission to top B-schools across the globe with significant scholarships.