News

Nearly 200 Harvard Affiliates Rally on Widener Steps To Protest Arrest of Columbia Student

News

CPS Will Increase Staffing At Schools Receiving Kennedy-Longfellow Students

News

‘Feels Like Christmas’: Freshmen Revel in Annual Housing Day Festivities

News

Susan Wolf Delivers 2025 Mala Soloman Kamm Lecture in Ethics

News

Harvard Law School Students Pass Referendum Urging University To Divest From Israel

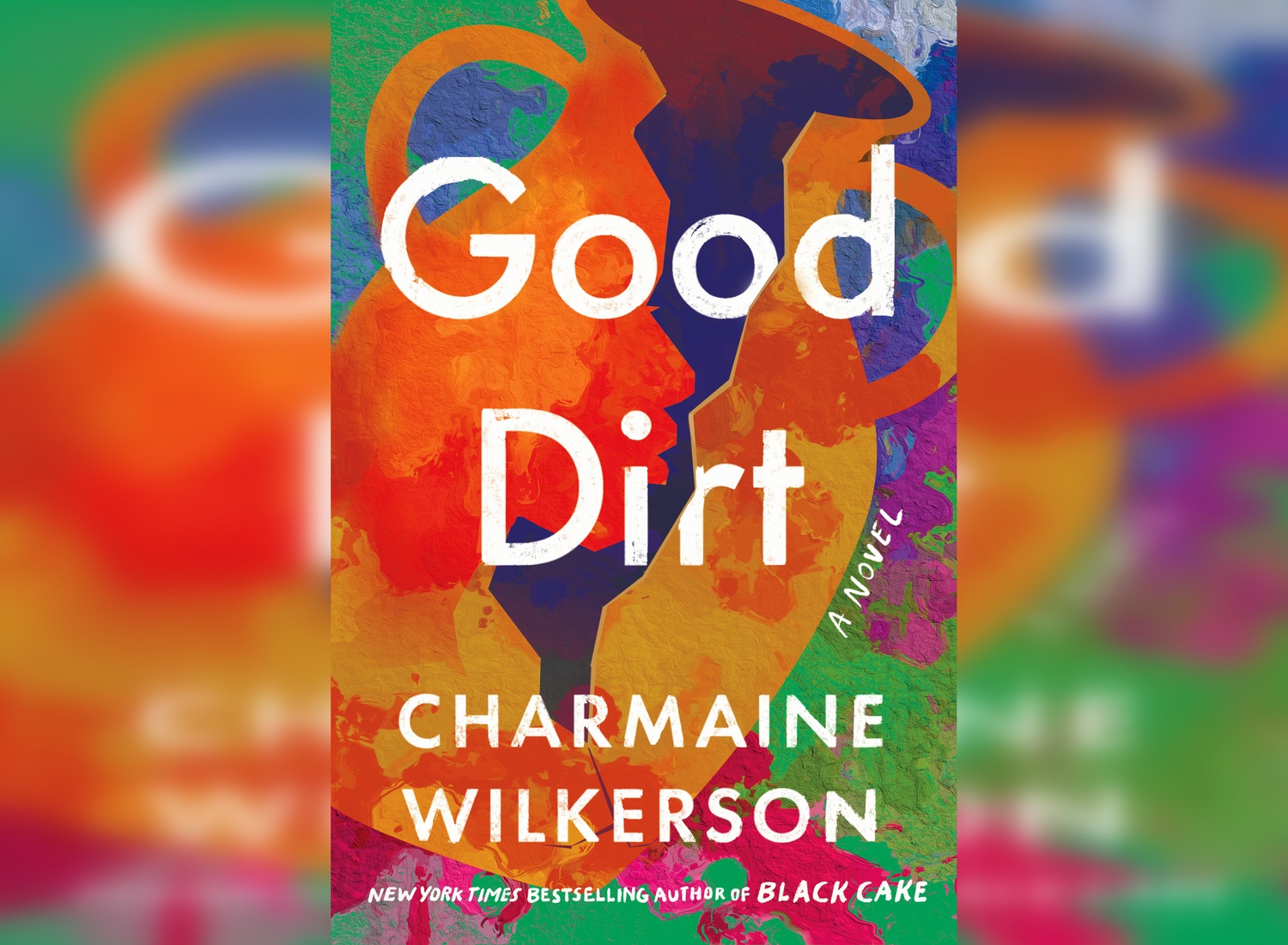

‘Good Dirt’ Review: A Story Worth Digging Into

4 Stars

Few can weave together past and present as masterfully as Charmaine Wilkerson. Three years after her debut novel “Black Cake” and two years after its adaptation into a Hulu original series, Charmaine Wilkerson released “Good Dirt,” a brilliant novel that dives into similar themes of inheritance, legacy, and ancestry.

While “Black Cake” centered on a family recipe, the main focus of “Good Dirt” is a 20-gallon antique jar, fondly named Old Mo after the initials “MO” inscribed on the jar’s lip. The jar is a beloved part of Ebony “Ebby” Freeman’s family history. Broken during a botched armed robbery that resulted in the murder of Ebby’s 15-year-old brother, it is within Old Mo’s vessel that the novel’s heart beats. Wilkerson intersperses Ebby’s story with those of her ancestors who held the jar before her, reimagining the jar’s — and the Freemans’s — identity through a narrative that flows between perspectives, decades, and generations.

Readers are welcomed into Ebby Freeman’s life just as she becomes a jilted bride, left on her wedding day in her coastal New England hometown. As her relationship crumbles in a discomfitingly public fashion, Ebby is left to grapple with the emotional fallout while still carrying the trauma from witnessing her brother’s death as a child. Ebby retreats to the French countryside in an attempt to repair some of the damage, seeking solace from the spotlight that is again affixed upon her, just as it was when her brother was murdered.

Wilkerson’s writing is lyrical and evocative, making the novel nearly impossible to put down at times. She seamlessly weaves multiple plotlines and moving parts, each of them almost equally engaging. The novel’s structure is rich in perspective, leaping between Ebby’s time in the French countryside, her parents’s childhood homes, the rocking wood slats of the slave ship that carried her family’s matriarch to Barbados, and the dusty walls of the pottery building where Old Mo was crafted. The titular “good dirt” carries multiple meanings: soil as a literal and metaphorical foundation — Ebby’s family history is fertile ground, and throughout the book, Ebby and the reader uncover just how much the past bleeds into the present.

One of the novel’s great strengths is Wilkerson’s commanding ability to spin her narrative across time and space. Alternating perspectives allow for a more expansive view of Ebby, her family, and surrounding characters. Throughout the book’s four parts, the reader engages with the thoughts of everyone in the intricate narrative, even Ebby’s charming yet skittish ex-fiancé, Henry, and his inquisitive new beau, Avery. The reader comes to understand the motivations of the book’s characters, as Wilkerson skillfully approaches their imperfections with empathy and without judgment. Even the novel’s romantic tones are handled with elegant subtlety, relying mostly on fade-to-black moments rather than in-depth scenes of intimacy.

Yet Wilkerson’s ambitious attempt at breadth requires a sacrifice. The momentum of the story is sometimes stifled because of these frequent shifts in point of view. At one point, readers are pulled out of an unceremonious reunion between Ebby and Henry and plopped into the story of Ebby’s ancestor’s capture.

“Good Dirt” serves readers a genre-blurring feast of storytelling — part mystery, part historical fiction, part fantasy, and part romance. However, Wilkerson’s formidable commitment to entwine many elaborate stories at once means that some characters and plots fall by the wayside. At one point, Ebby and Avery suspect Henry of murder, a plot built up over multiple chapters — and rather uncharacteristic for Henry — just for Henry to quickly be cleared of the crime and the plot to be forgotten. This tendency leaves certain arcs feeling like pottery in need of a final burnishing.

There are also moments when the dialogue in “Good Dirt” feels mechanical, when the novel’s characters speak to one another like characters written in a book as opposed to real people. In the book’s final quarter, difficult conversations are rushed and grazed over, the weight of important revelations diminished by a sense of haste. The third and fourth acts, which linger too long in what feels like a repetition of earlier chapters, suddenly shift into rapid-fire resolution, where many of the novel’s earlier conflicts are tied up with an almost too-neat efficiency.

Nevertheless, Wilkerson’s approach, while occasionally disorienting, is still brave. Rather than a traditional linear narrative, she allows the story to unfold in a way that mimics memory itself — fragmented, fluid, and thoroughly emotional. In this sense, the novel’s ebbing momentum is a deliberate stylistic choice.

“Good Dirt” is a stunning and deeply affecting novel. Wilkerson reaffirms her place as a dextrous storyteller, crafting a narrative that is both sweeping in scope and intimate in detail. The novel is a poignant meditation on heritage and memory, and what it means to hold dear the people who have begotten you.

–Staff writer Jorden S. Wallican-Okyere can be reached at jorden.wallicanokyere@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X @jordensanyyy.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

Most Read

- Harvard Suspends Research Partnership With Birzeit University in the West Bank

- 2 Years After Affirmative Action Ruling, Harvard Admits Class of 2029 Without Releasing Data

- Give the Land Up — Or Shut Up

- More Than 600 Harvard Faculty Urge Governing Boards To Resist Demands From Trump

- Harvard Students Don’t Need To Work Harder. Administrators Do.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

With innovative financial tools combined with financial education, Collegiate empowers students to take control of their finances and build confidence in their money management skills.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

Admit Expert is a premium MBA admissions consulting company, helping candidates secure admission to top B-schools across the globe with significant scholarships.