News

Nearly 200 Harvard Affiliates Rally on Widener Steps To Protest Arrest of Columbia Student

News

CPS Will Increase Staffing At Schools Receiving Kennedy-Longfellow Students

News

‘Feels Like Christmas’: Freshmen Revel in Annual Housing Day Festivities

News

Susan Wolf Delivers 2025 Mala Soloman Kamm Lecture in Ethics

News

Harvard Law School Students Pass Referendum Urging University To Divest From Israel

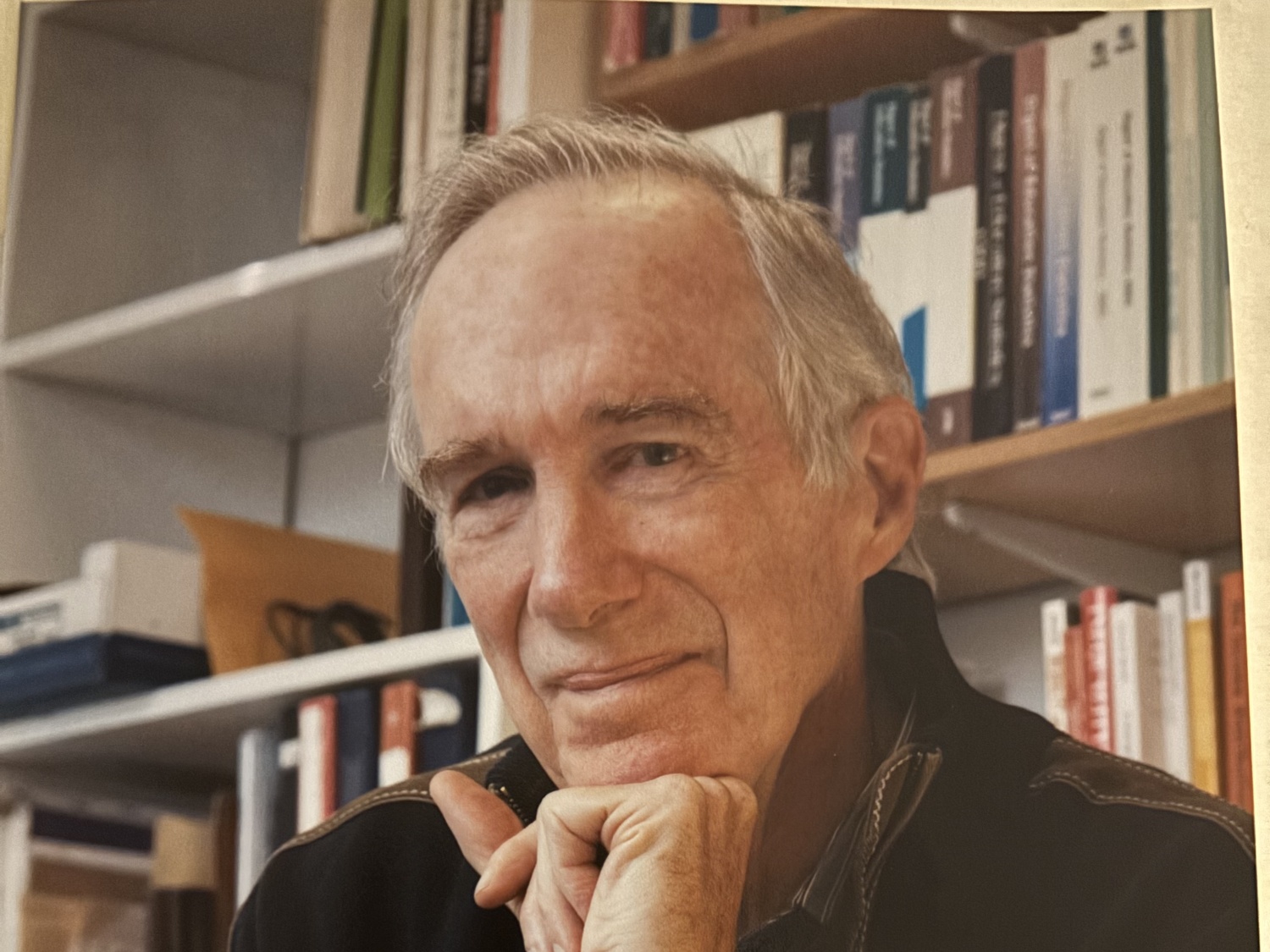

Sociologist Christopher Jencks Remembered As a Fearless Skeptic, Exceptional Mentor

When Kathryn J. Edin started graduate school at Northwestern University, she did not have big dreams. She had gotten into the doctorate program off the waitlist with mediocre math scores, and she wanted nothing more than to teach at a small liberal arts college.

But that was all before she met Christopher S. “Sandy” Jencks ’58.

Then a professor of sociology at Northwestern, Jencks hired Edin as a part-time researcher. After working together for five years, they published a ground-breaking article based on Edin’s dissertation. Two decades down the road, he testified on her behalf before Harvard’s faculty hiring committee, after which she received tenure. And until a few years ago, he was still editing her papers.

“He made my career,” said Edin, who is now a sociology professor at Princeton University. “Sometimes you meet somebody, and it just changes everything.”

Jencks nurtured others, too. Jal D. Mehta ’99, a professor of education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, called Jencks “the best advisor I or anyone could have asked for.”

“He took a lost graduate student and helped me find a direction and scholarly identity, even though it was very different from his own,” Mehta wrote in a statement.

Former Harvard Kennedy School Dean David T. Ellwood ’75 called Jencks “the titanic figure” in the field of sociology.

“If you look at so many people in the field that really did make a difference — a huge fraction were Sandy’s students,” Ellwood said. “He was the best mentor and collaborator practically I’ve ever seen.”

Jencks, who moved from Northwestern to HKS in 1996, died at his home on Saturday, Feb. 8 from complications of Alzheimer's disease. He was 88.

Jencks is survived by his wife, Harvard Kennedy School professor Jane J. Mansbridge; their son Nat; their grandson Wilder, and a brother, Stephen.

“He was the smartest man I’d ever met. And a fixer by nature,” Mansbridge wrote in a statement. “Whether it was the broken latch on the door or the societal inequality that we struggle under every day, he tried to figure out a way to make it better.”

‘A Breath of Fresh Air’

Remembered by legions of colleagues and students as a scholar who challenged conventional wisdom and asked the hard questions, Jencks was “the world expert” on inequality, according to Johns Hopkins sociology professor Amy Binder, one of his doctoral students at Northwestern.

Binder, whose area of focus had little overlap with Jencks’ expertise, still hunted him down to advise her dissertation.

“I didn’t do work that looked anything like what he did, but I had taken a class with him,” Binder said. “I loved his clarity. I loved the way he thought. I loved how he was very generous, but also skeptical of people’s initial findings.”

Jencks’ skepticism led him to question the status quo — and often led him to unexpected, and sometimes unpopular, findings.

In the early 1970s, he published a book that exposed the inadequacy of various social policy interventions of the prior decade, including liberal education reform. It was a “very upsetting but unambiguous” conclusion, Ellwood said.

“He got pilloried by many people because they didn’t like what he found, and drove desperately to prove him wrong, and they didn't,” Ellwood added.

Time would validate Jencks’ conclusion. Rather than an expansive social safety net, his book proposed more direct intervention — what he coined a “negative wage tax” and what we now call an earned income tax credit. A year later, President Gerald Ford followed his lead, enacting the first ever EITC.

Later, in an article for The American Prospect co-authored with Edin, Jencks zeroed in on deficiencies in welfare programs, finding that welfare recipients also had to keep illicit jobs to make ends meet.

“Any given statement that people just accept, he would say, ‘Oh, how is that possibly true?’” Edin said. “So he inbred this skepticism of the conventional wisdom.”

“His view about both research and teaching and maybe life, I think, was: It’s really important to ask the right question,” Government professor Jennifer L. Hochschild said. “Once you’ve asked the question, the answer should be, in effect, allowed to go wherever it’s going to go.”

Jencks’ reputation for loyalty to facts over ideology may have dismayed some, but it made Jencks exceptionally popular among academics and experts alike.

Former California governor Jerry Brown remembered calling Jencks “out of the blue” over the course of his career for guidance on welfare issues. He described Jencks as a “giant” in the field whose research and writing influenced Brown’s approach to social policy.

“I didn’t feel he was an ideologue or partisan,” Brown said. “He was just telling it the way he saw it. It was a breath of fresh air.”

‘Dozens and Dozens of Red Marks’

Born in Baltimore on Oct. 22, 1936, Jencks attended Harvard as an undergraduate, where he studied English and wrote for The Crimson. He also received his master’s degree from HGSE, but never obtained a Ph.D.

Jencks then began his career as a journalist, working as an editor at The New Republic. He was later part of the brain trust behind The Prospect.

“He was an exceptionally clear writer, and very accessible,” Paul Starr, co-founder of The Prospect, said. “So he could take a complicated topic and explain it in a way that anybody could understand, and that is a hugely important skill.”

His stint as a journalist made him a great writer, but colleagues and students said he was an even better editor.

“He also marked up my writing — line by line, word by word — in ways that no other teacher, before or since, ever did, setting a daunting example for what it means to be a good advisor,” Mehta wrote.

Jencks’ red editing pencil was famous among his peers.

“If Sandy edited a paper of yours, the good news is you got spectacular advice,” Ellwood said. “The bad news is every page had dozens and dozens of red marks on it.”

“Usually there were more comments on the page, usually written in red pencil, then there were typed words,” Edin added.

At 57, Edin — by then a tenured professor at Princeton and an eminent scholar in her own right — sent Jencks one last paper to review.

“There were more words on the page than comments, and I was kind of shocked, and I looked really carefully, and in the margins, at one point it said, ‘good,’” Edin recalled. “It was hilarious that at 57 I thought, ‘Okay, I’ve made it.’”

‘Sheer Decency and Goodness’

Those that knew Jencks said that he was universally admired for his brilliance — Hochschild guessed that he “had an IQ higher than most of us combined.”

His intellect, however, was accompanied by a remarkable lack of ego.

Julie B. Wilson, a senior lecturer in social policy at HKS, said Jencks didn’t care about flaunting his rank or intelligence, distinguishing him from other faculty members.

“Sandy was the smart person in the room, but he really fit into the conversation, and was part of the group, and he was a very comfortable person to talk to, to ask questions of, to test ideas around.”

Jencks often used humor to put people at ease, his students and colleagues said. According to Binder, he approached conversations with a smirk and a smile in “the kindest, most generous way.”

“He was a very funny person who wanted to laugh,” Binder said. “He wanted to find humor in things.”

Lunches with Jencks offered exclusive access to his wit, curiosity, and kindness.

“He had a perspective on the world that often took the form of a sense of humor, but also wisdom,” Hochschild said. “Conversation about lunch, it could be, it wasn’t necessarily always heavy and complex. It was just, ‘Do you really think this food goes with that food?’”

“There was nothing better than sitting down to have lunch and talking with Sandy,” Ellwood added. “Could be about your work. It could be about whatever else is going on. He was good for you.”

Jencks was married to Mansbridge, professor emerita at HKS, for 49 years.

“He liked to work a lot,” Mansbridge wrote in a statement to The Crimson. “He liked quiet evenings at home. He liked to sail. He liked talking with Nat and me and our friends. I can’t describe in words the warmth we shared.”

Together, Mansbridge and Jencks were an intellectual force.

“If you know his wife, Jenny, she’s the other smartest person in the world,” Edin said. “So we would just have these incredible conversations that you rarely have with other people.”

Professor of Government Michael J. Sandel wrote in a statement to the Crimson that both Mansbridge and Jencks shared not only academic prowess but “sheer decency and goodness.”

“Both Sandy and Jenny are shining examples of how character can go hand-in-hand with scholarly renown,” Sandel wrote.

—Staff writer Elise A. Spenner can be reached at elise.spenner@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X at @EliseSpenner.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

Most Read

- Harvard Suspends Research Partnership With Birzeit University in the West Bank

- 2 Years After Affirmative Action Ruling, Harvard Admits Class of 2029 Without Releasing Data

- Give the Land Up — Or Shut Up

- More Than 600 Harvard Faculty Urge Governing Boards To Resist Demands From Trump

- Harvard Students Don’t Need To Work Harder. Administrators Do.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

With innovative financial tools combined with financial education, Collegiate empowers students to take control of their finances and build confidence in their money management skills.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

Admit Expert is a premium MBA admissions consulting company, helping candidates secure admission to top B-schools across the globe with significant scholarships.