Harvard Researchers Brace for Impact As NIH Threatens To Limit Support For Indirect Costs

By Dhruv T. Patel and Grace E. Yoon, Crimson Staff WritersAfter a Feb. 7 order from the National Institutes of Health attempted to slash federal funding for overhead expenses tied to research projects, researchers across Harvard feared their work was in limbo.

The NIH awarded Harvard more than $488 million in grants in fiscal year 2024, $135 million of which covered indirect expenses. Under the proposed limits on overhead costs, which have been temporarily blocked by a federal judge, that total — which supports everything from animal labs to the regulatory bodies that oversee clinical trials — could have dropped to $31 million.

In statements and interviews with The Crimson, nine life sciences researchers at Harvard — from the Harvard School of Public Health, Harvard Medical School, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and School of Engineering and Applied Sciences — said limits on indirect cost reimbursements would put critical research and administrative teams on the chopping block.

The Feb. 7 directive drew a sharp and immediate response from Harvard administrators — frequent communications from department heads and emails from University leadership, including Harvard President Alan M. Garber ’76.

And on Thursday, Vice Provost for Research John H. Shaw offered nervous SEAS and FAS faculty a meeting to discuss the funding cuts face-to-face.

During the meeting, Shaw — who was joined by SEAS Dean David C. Parkes and Jeff W. Lichtman, dean of the FAS’ Science division — said he worried about the state of Harvard’s research if indirect reimbursements were cut, but urged faculty members to continue their research without pause, according to Applied Physics professor of the practice David C. Bell, who attended the meeting.

But when Bell asked Shaw and other administrators about the magnitude of the impact the order would have on staffing and research at Harvard, they didn’t have an answer.

“It’s unclear,” they said, according to Bell.

Shared Infrastructure

The federal order would have forced Harvard to charge the NIH at most 15 cents in overhead costs for every dollar spent on research — a significant drop from the 69 cents the University currently charges.

Unlike grants, which are won by individual principal investigators, indirect expenses are distributed by Harvard administrators from a general pool of money awarded by the NIH.

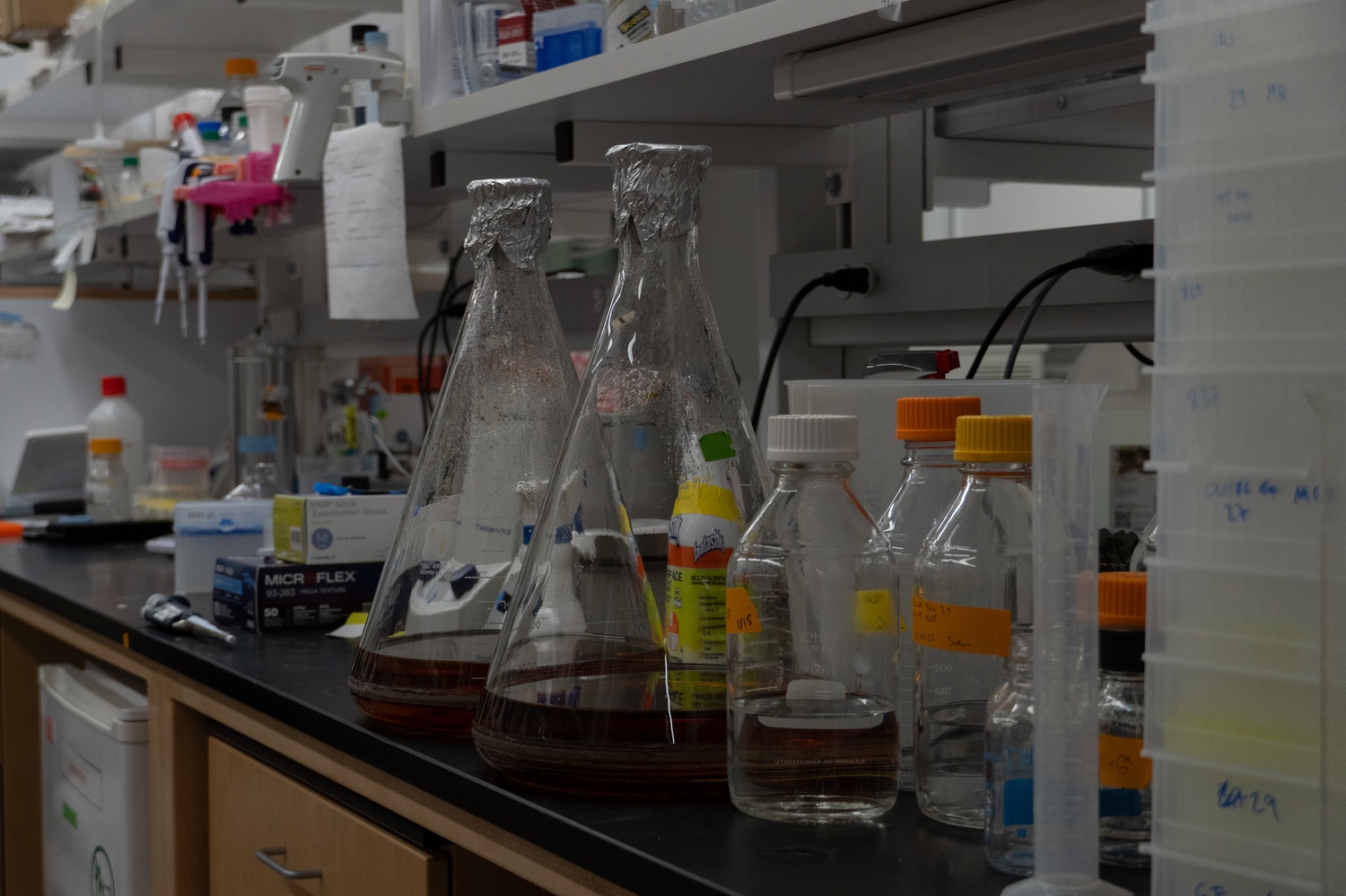

Indirect expenses fund the rent, equipment, and utilities needed to maintain research projects. They also fund oversight teams like the Institutional Review Board, which is responsible for approving any studies involving human subjects.

Some researchers said they worried the overhead limits would cut the flow of money to specialized facilities and resources that are shared across labs.

Joan S. Brugge, a professor at HMS, wrote in an email that her lab hosted data on Harvard-wide servers and relied on the Countway Library for access to proprietary scientific reports — shared resources, she said, that would be affected first if Trump’s order took effect.

“If the indirect costs are cut dramatically, we would still have salary for research staff and funding to buy supplies, but the University would have to cut services that are essential to carry out the research and we would be crippled,” she wrote.

Richard M. Losick — a retired Molecular & Cellular Biology professor whose lab relied on NIH funding for more than five decades — said animal facilities, like the mice lab under the BioLabs, were particularly vulnerable because of their status as shared resources for researchers across Harvard.

Some research centers at Harvard extend their services to researchers for a fee — a model that could quickly be tested under the Feb. 7 directive.

Louise Trakimas, a research assistant at the Electron Microscopy Core Facility, said the funding shortages labs could face if the order passed would have directly challenged the use of her team’s services.

“We aren’t relying on any NIH grants because we’re a fee-for-service facility, but it’s going to trickle down to us,” she said. “Because if people aren’t getting their funding, they’re not going to be able to afford to use our services, so it will affect us.”

‘Dismantling the System’

Indirect funding awarded by the NIH also covers oversight bodies at Harvard that manage research and ensure compliance with federal regulations.

Those include Harvard’s institutional review board — a federally mandated body responsible for approving any studies involving human subjects at the University — and the Environmental Health and Safety Office, which oversees research involving hazardous chemicals.

A cut to indirect reimbursements would directly threaten the ability of these two bodies to oversee research at Harvard, Shaw wrote in a declaration accompanying a Sunday lawsuit filed by thirteen colleges — but not Harvard — against the order.

HMS professor Jeremy M. Wolfe said the loss of indirect cost recovery could require Harvard and affiliated hospitals to furlough staff in offices that manage grant applications, ensure research follows federal regulations and ethical guidelines, and submit compliance reports.

“If you start dismantling the system, then it would become very difficult to apply for the new grants that are required on a continuing basis to keep your work going,” he said.

Shaw wrote in his declaration that the loss of indirect funds could force the University to cut staffing at its IRB.

“That would in turn lead to substantial delays in critical research that relies on human subjects, including projects funded by NIH,” he wrote.

HSPH professor Sarah Fortune said the order’s passing would challenge her lab’s ability to provide privacy measures for human subjects in her research on tuberculosis.

“Would it stop tomorrow?” Fortune said. “No, probably, because we’d limp along for a little while and try to figure out what the offramp looks like.”

But she said her research would quickly become unsustainable without the indirect cost recovery that funds containment labs that conduct infectious disease research and regulatory bodies that protect data security.

“Infrastructure required to do what we do safely and at the highest level is so complicated that — in the absence of indirect cost-supported infrastructure — I do not think that we would be able to do at all what we do,” she said. “There is no halfway.”

Dianne Bourque, a healthcare attorney at the Boston law firm Holland & Knight, said that when research loses funding, universities face a choice: cover the costs out of pocket, or trim the study down to use only the more limited funds.

But Bourque said that many cases may be all-or-nothing. Studies follow specific protocols approved by federal authorities, and those protocols determine the contractual obligations between researchers and human subjects. If researchers are unable to adhere to the determined contract, projects may simply shut down, according to Bourque.

Even the process of closing an experiment poses challenges.

“A bunch of sick patients have volunteered to have an intervention of some sort — like get a device implanted in them or swallow something that’s untested to see if it helps them,” Bourque said. “Now that you can’t carry out the study the way you had planned scientifically and budgeted, you’ve got to figure out what to do, because those people can’t just sit in limbo.”

Corrections: February 14, 2025

A previous version of this article incorrectly referred to David C. Bell on one reference as an Applied Physics professor and on another as a Computer Science professor. In fact, Bell is a professor of the practice in Applied Physics.

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Bell leads Harvard’s Center for Nanoscale Systems. In fact, Bell manages the CNS’ imaging and analysis facilities.

A previous version of this article incorrectly referred to Richard M. Losick as a former Harvard Medical School professor. In fact, Losick taught in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, not the Medical School.

Correction: February 21, 2025

Due to incorrect information provided by Bell, a previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the CNS gets most of its money from indirect costs. In fact, the CNS is classified as a specialized service facility, and its funding mechanisms do not contribute to Harvard’s indirect cost rate.

—Staff writer Dhruv T. Patel can be reached at dhruv.patel@thecrimson.com. Follow him on X @dhruvtkpatel.

—Staff writer Grace E. Yoon can be reached at grace.yoon@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X @graceunkyoon.