They Won’t Let Sacco and Vanzetti Die

Sacco and Vanzetti are interred, not in a tomb — their bodies were cremated shortly after their executions — but in an archive, a testament to a radical tradition and the first Red Scare which sought to disrupt it. In the Community Church of Boston, their memory has found a temporary resting place. By Mae T. Weir

By Mae T. Weir

They Won’t Let Sacco and Vanzetti Die

Sacco and Vanzetti are interred, not in a tomb — their bodies were cremated shortly after their executions — but in an archive, a testament to a radical tradition and the first Red Scare which sought to disrupt it. In the Community Church of Boston, their memory has found a temporary resting place.Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti have been arrested in time on the third floor of the Community Church of Boston.

They are interred, not in a tomb — their bodies were cremated shortly after their executions — but in an archive, a testament to a radical tradition and the first Red Scare which sought to disrupt it. In the Church, their memory has found a temporary resting place.

The Community Church of Boston, originally, was not bound by a building. In its salad days, it was a roving congregation that filled grand concert halls with eager Boston reformers. These meetings sparked an illustrious and ongoing speaker series, featuring the likes of W.E.B. DuBois, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Angela Davis.

Today, the Unitarian Universalist church has settled into a nondescript office building between a Chick-fil-A and a liquor store. From a perch in Copley Square, the Church stretches far beyond itself, seeking spiritual and intellectual solidarity with places like El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Palestine.

Their modern solidarity work traces back to the Church’s founding in 1920, and to Sacco and Vanzetti themselves.

In the early 1920s, Sacco and Vanzetti — two Italian immigrants, workers, and political anarchists — were arrested and tried for the robbery and murder of two payroll guards in Braintree, Massachusetts.

The case against them was flimsy, largely based on the guns possessed by the two men. It was bolstered only by withheld evidence, badgering interrogations, and disregard for their witness-corroborated alibis.

From their conviction in 1921 to their executions in 1927, the case provoked outrage and spurred grassroots mobilization. An explosive microcosm of the ongoing Red Scare, the charges against Sacco and Vanzetti occurred during the time of the Palmer Raids. From 1919 to 1920, a fledgling FBI indiscriminately rounded up thousands of immigrants and perceived political dissidents across the United States. Hundreds were deported.

Sacco and Vanzetti adhered to a revolutionary politic that advocated for direct action against the ruling class and the state. Dissatisfied by reformist tactics, their anarchism held that the capitalist order needed to be uprooted — urgently.

For sympathetic contemporaries and modern left-wing historians alike, the case against Sacco and Vanzetti represents the weaponization of the American criminal legal system to squash dissent, particularly within working-class immigrant communities.

“We sort of call them our martyr patron saints,” Dean P. Stevens, the Church’s current leader, tells me. In the 1920s, the upper-class founders of the Church rallied around the campaign to free Sacco and Vanzetti.

Stevens, who rarely appears without his charcoal “PALESTINE” baseball cap, is a man of many hats. Officially, he is the Church’s Administrator and Music Director. Unofficially, he lists in an email to me, he is their toilet cleaner, snow shoveler, purveyor of too many things, and “Fake Minister.” But to me, Stevens is my guide as I descend into the captivating and oft-improbable Boston histories.

These histories spill from the Church’s building and into the streets, solidifying the Church’s entanglements with Sacco and Vanzetti, even a century later.

The afterlife of their case — and the Church’s legacy of allegiance with the two men — takes on a physical embodiment in the meticulously collected archive on the third floor. It is the passion project of a small circle of historically scrupulous Boston-based anarchists. The materials have passed from the hands of Bob D’Attilio to Jerry B. Kaplan, both founding members of the “Sacco and Vanzetti Commemoration Society.”

The Commemoration Society and the Church have taken on a niche historical mantle. In their nostalgia for 1920s radicalism — expressed in the archive, marches, and one yearly award — they stretch threads to connect the case to a smattering of modern liberation movements.

In doing so, they seek to infuse their modern activism with the memory of Sacco and Vanzetti, almost 100 years after they met their fates in the electric chair.

The Memory Keepers

In Bob D’Attilio’s professional life, he was a stage manager of a Cambridge theater company. At work, some did not know that in another world, he doubled as an internationally renowned scholar of the Sacco and Vanzetti case.

If there was an event in the local community about Sacco and Vanzetti — whether at Cambridge’s Dante Alighieri Society, the Boston Public Library, or the Community Church of Boston — D’Attilio was almost certainly its organizer, if not its keynote speaker.

Howard Zinn, the author of “A People's History of the United States” and a frequent speaker at the Church, even dubbed D’Attilio “Mister Sacco and Vanzetti.”

D’Attilio also helped found Boston’s Sacco and Vanzetti Commemoration Society, where he and Kaplan first met. Both have dedicated themselves to the impassioned excavation of minute details of the Sacco and Vanzetti case.

A dogmatic historian but an unstructured archivist, D’Attilio filled both floors, the attic, and the basement of his home in Medford with Sacco and Vanzetti ephemera and rare Italian anarchist materials.

“He — at some point probably in the early seventies — began to contact people who were connected to the case, either directly or indirectly,” Kaplan says.

If the anarchists themselves were already dead, D’Attilio tracked down their living descendents. From these sources, he amassed around 2,000 letters written by old anarchists.

The anarchist Raffaele Schiavina, for example, prominently campaigned to free Sacco and Vanzetti. He had previously been deported from Massachusetts to Italy for World War I draft-dodging, but eventually smuggled himself back into the U.S. in 1928, bearing an anglicized name — Max Sartin.

Roughly fifty years later, D’Attilio tracked Sartin down and, together, they published an English translation of a set of essays by the militant anarchist Luigi Galleani, titled

“La Fine Dell’Anarchismo?” or “The End of Anarchism?”

D’Attilio also inherited Sartin’s original copies of Cronaca Sovversiva, meaning “Subversive Chronicle,” an anarchist publication Sartin created and circulated despite bans in both the U.S. and Italy. Kaplan believes this is likely the only complete set that still exists.

D’Attilio always intended to write a book, Kaplan says. But when the historian Paul Avrich wrote “Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background,” D’Attilio’s project — and his dream — were dashed. Pulling the Avrich text from a shelf each time he recounts this story, Kaplan says that it was more or less the exact book D’Attilio had spent decades preparing to pen.

When D’Attilio passed away in 2020, he left no will. Kaplan managed to obtain the keys to his Medford home, however, and gained access to the collection of curios for the first time.

“It was not a good idea to ask him if you could come over and see it. You had to wait until you were invited,” Kaplan says of D’Attilio.

“So I waited for an invitation, which never came,” he adds.

Over eighteen trips, Kaplan cleared the house of its trash and treasure. The distinction between the two was not always clear. Kaplan recalls discovering a 1930s letter, sandwiched within a stack of D’Attilio’s personal mail.

If it were not for Kaplan’s intervention, everything in the house may have been discarded wholesale.

Instead, Kaplan scooped up the objects orphaned from their collector. He brought them to the doorstep of a progressive congregation: the Community Church of Boston.

Brahmins and Bombs

For Stevens, Sacco and Vanzetti have been embedded in the Church from its inception.

“The Church was founded in 1920 in an attempt to humanize religion and to get it involved in the social problems of the day,” Stevens says. “A lot of it was a response to World War I and the war profiteering and the senselessness of the slaughter.”

From the start, the Church mobilized around the effort to free Sacco and Vanzetti. In September of 1921, they held their first recorded event — a “Sacco and Vanzetti Community Supper” that raised $71 for their defense committee.

After the arrest of Sacco and Vanzetti in Brockton, Mass., the streets erupted in outrage — not just in Boston, but in New York, Buenos Aires, and Johannesburg. After an unfair trial and guilty verdicts, protests escalated, including a general strike called by the Industrial Workers of the World.

But the defense of these two Italian anarchists drew the patronage of an unlikely ally — the progressive women of the “Boston Brahmin,” an old-moneyed class of oft-Harvard-educated WASPs.

According to Stevens, the Boston Brahmin were “driving forces behind the organization and the forward movement of the Church.”

Though D’Attilio’s materials now reside in the Church, they make few references to the support of its liberal members. Instead, D’Attilio’s method of curation — targeting former anarchists — provides a glimpse into the grassroots organizing and radical press of working-class Italian immigrants.

Stevens, on the other hand, acts as an authority on the Church’s Brahmin foremothers. He has scoured decades of his so-called “rich feast” of early Church records, stored in binders and boxes on the fifth floor.

“The archives of Community Church are something that could just take you and grab you and not let you go,” Stevens says.

According to Stevens, Gertrude L. Winslow, a founder and secretary of the Church, befriended Vanzetti and visited him often in jail, where she taught him English. “At the time of his execution, she was in Italy, visiting Vanzetti’s family,” he says.

Another member, Elizabeth Glendower Evans, willed her estate to Sacco’s living relatives. Stevens claims her family intervened and prevented the fulfillment of her wishes.

Sergio R. Reyes, another founding member of the Commemoration Society, says he finds a “great contradiction” in the Brahmin support for anarchists. Reyes says he believes that while Vanzetti seemed open to the Brahmins’ support, Sacco was more distrustful.

“These people who were trying to help them were based not so much on the radical transformation of society whatsoever,” Reyes says. “They were not anti-capitalists. They were humanists.”

Not all Brahmin, however, were willing to foot Sacco and Vanzetti’s legal fees or campaign for a retrial. Instead, the archive sheds light on the involvement of one particular Brahmin, slammed in the anarchist press as responsible for the men’s death — Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell.

Mere months before the scheduled executions, Massachusetts Governor Alvan T. Fuller caved to increasing public pressure. He appointed former judge Robert A. Grant, MIT president Samuel W. Stratton, and Lowell to conduct an impartial review of the case. Within two weeks, the eponymous “Lowell Committee” sided with the original verdict, rejecting the possibility of commuting their death sentences.

According to Reyes, the selection of elite university presidents sent a message to the public. “What they were saying was: ‘Look at this, the best minds, the best intellectuals of our society, agree with us,’” Reyes says.

But at Harvard, the fruits of Lowell’s mind included a witch hunt against gay students, the eviction of all Black students from housing in the Yard, and an attempted quota to limit the number of Jewish students. In Lowell, the state of Massachusetts had found an authority known for throwing his weight in the no-holds-barred defense of the white, Brahmin class.

Other Harvard intellectuals, however, did not side with their president.

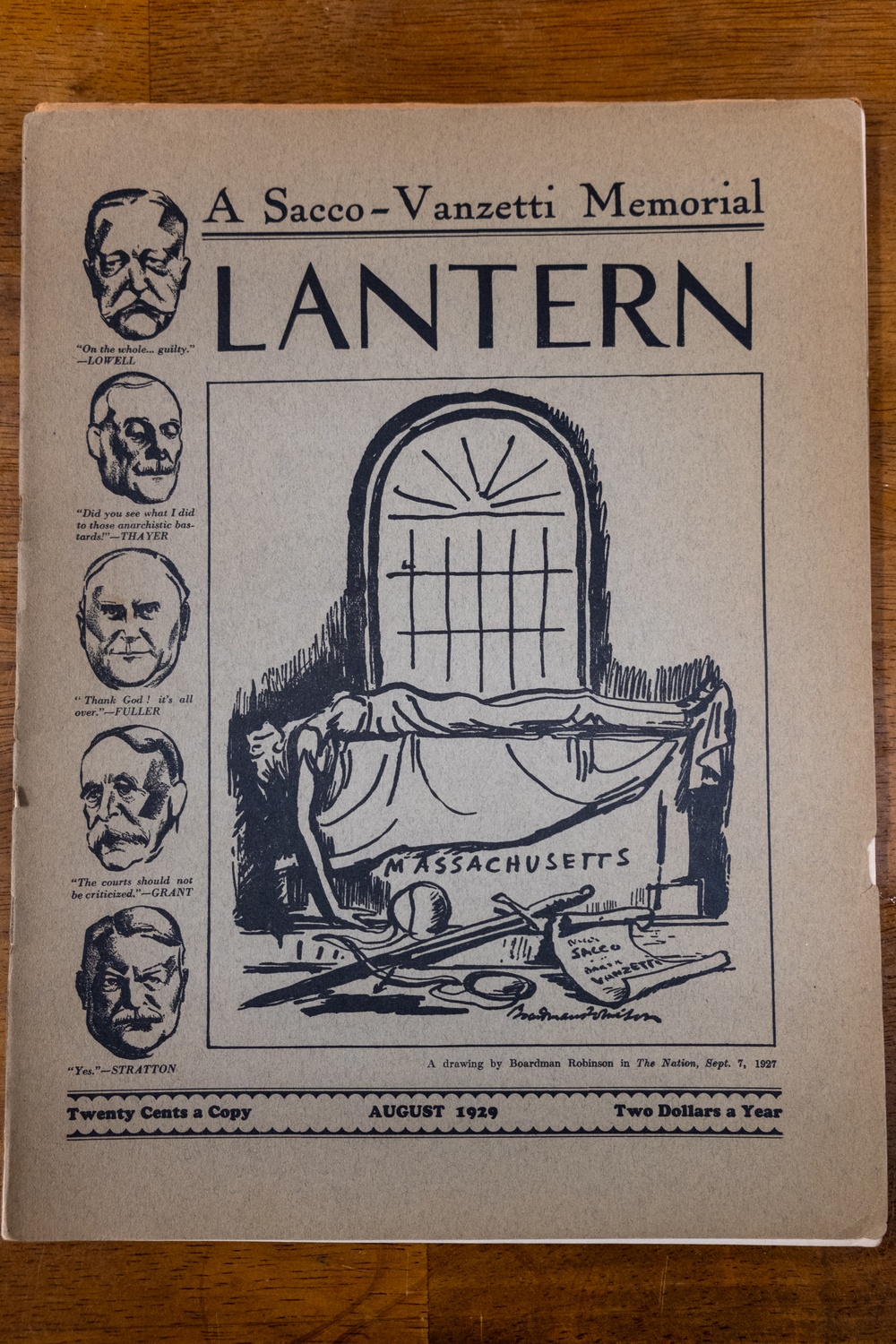

On a shelf in the Church’s archive, a 1929 copy of The Lantern — a counter-culture Boston publication — is an English-language record of dissent on the two-year anniversary of the executions. Past a cover bearing a cartoon of Lowell, the edition contains the reflective condemnations of Harvard history professor Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr.

“History already sees Sacco and Vanzetti as the victims of a faulty judicial system administered by men blinded by post-war hysteria and passion,” he writes.

Immortalized in Print

Today, Sacco and Vanzetti occupy a perch above their archive. A poster affixed above a bookcase bears a black-and-white sketch of the two men — solemn, nearly expressionless, joined by handcuffs.

Under the sketch are some of the last words that Vanzetti, an avid reader and poetic writer, ever penned from his prison cell.

“Never in our full life could we hope to do such work for tolerance, for justice, for man's understanding of man, as now we do by accident,” he writes.

“That last moment belongs to us — that agony is our triumph,” he concludes.

The Church’s archive is now a temporary home for materials memorializing their deaths and celebrating the political reverberations of their “triumph.”

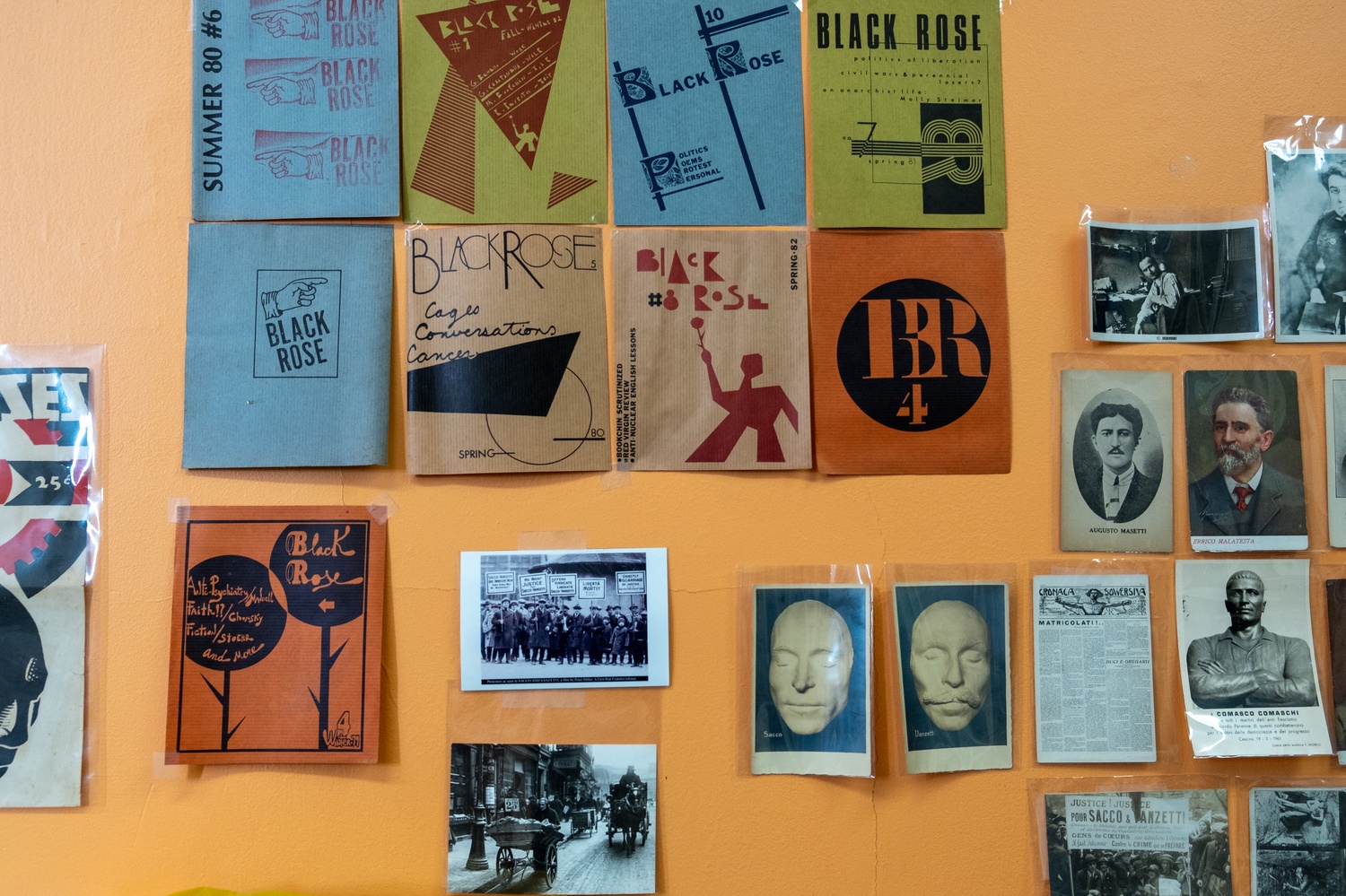

The walls are papered over with laminated postcards of Rosa Luxemburg and other European radicals. Posters announce the lecture series of the Black Rose Anarchist Federation of the late 20th century, where Noam Chomsky was a regular contributor.

Over the past three years, Kaplan has transformed the chaos of memories that once cluttered D’Attilio’s home into a proper archive. Radical history is packaged pristinely and sorted onto labeled shelves.

To the left of the door, a folding table is stacked high with copies of L’Adunata dei Refrattari, meaning “The Gathering of Refractories,” a Sartin-edited newspaper founded in 1922 as a public forum for Italian anarchists.

“People think that anarchists don’t organize, but that’s certainly not true,” Kaplan says. “I mean, look at all the newspapers they put out.”

During one archive visit, Kaplan removes several copies of “La Salute è in voi!” — meaning “Health is in you!” — from their plastic covers. Initially published by the anarchist Galleani in 1905, it contains a formula for making nitroglycerine, a component of homemade bombs and encourages “audacious revolt” against oppressors. Off the page, Galleani’s adherents were suspects of the 1920 Wall Street bombing — an alleged retaliation for the Sacco and Vanzetti arrests — but no one was ever charged.

Neither Kaplan nor I can decipher the bombmaker’s pamphlet right in front of us. We do not read Italian fluently. And we certainly cannot understand the letters of Sacco, Vanzetti, and Galleani in the archives, all written from prison in gorgeous but illegible script.

Despite his profound interest in these figures, Kaplan often jokes that he doesn’t mind his inability to read their Italian writing. If he did, he says, he would spend all day reading and never get his work done.

For Kaplan, “work” is the task of collecting and cataloging. He has done so meticulously over the past three years of his retirement.

Kaplan is less willing, however, to forecast how we should read these remnants of 1920s history today.

“I see my job as the one who organizes the collection,” Kaplan says. “I leave it to others to go through it and determine its value.”

The Cadre of Commemoration

Seventy-nine years after their death, Sacco and Vanzetti were reborn on the streets of Boston. With effigies and banners raised, around hundred demonstrators marched through Jamaica Plain to Forest Hills Cemetery, where the men had been cremated.

There, two young men impersonated Sacco and Vanzetti, the latter wearing a faux moustache glued lopsided above his lip. In front of two cardboard-and-paste coffins, they led the crowd in a mock funeral service.

Sacco and Vanzetti’s actual funeral drew about 200,000 Bostonians into the city streets, leading to confrontations with the police. In 2006, their circle was smaller —

and the activists who wanted to keep Sacco and Vanzetti alive on Boston’s streets first approached the police with their plan and expected number of attendees.

Jake P. Carman, a member of the Boston Anti-Authoritarian Movement, helped organize the march. He says two striking parallels at the time — ongoing state surveillance of anarchists and political threats against undocumented immigrants — inspired the first Sacco and Vanzetti Commemoration Parade.

“Sacco and Vanzetti died because they lived in a country and time where immigrants and radicals faced brutal political repression. If we look around, the same is true today,” wrote the Boston Anti-Authoritarian Movement, in a text announcing the memorial parade.

The 2006 demonstration sparked the formation of the Sacco and Vanzetti Commemoration Society, to which D’Attilio, Kaplan, Reyes, and Carman belonged. The Society organized yearly marches, usually around Paul Revere Mall and in the North End, until 2015.

But even in the historically Italian-American neighborhood, the protests did not always strike a chord.

“It’s so painful, and actually tragic, and also funny that sometimes people thought we were promoting another restaurant in the North End,” Reyes says. “The Sacco and Vanzetti Restaurant.”

The Community Church of Boston, however, has prided themselves upon keeping the men’s names relevant since 1976. In its yearly Sacco-Vanzetti Award for Social Justice, they seek out and honor those they view as the modern, political descendents of their “martyr patron saints.”

The list of recipients of the Church’s Sacco-Vanzetti Award hangs in their second-floor gathering space, alongside a massive plaque bearing the two men’s likenesses. Gifted to “outstanding activists’ in the people’s struggles,” many of the award’s recipients are storied and infamous.

Amongst them — César Chávez, Leonard Peltier, Mumia Abul-Jamal, Julian Assange, Rachel Corrie, S. Brian Wilson — a common trend arises. These recipients not only fought against oppressive systems but were often burned back — imprisoned for life, self-exiled and fighting extradition, crushed by bulldozers and trains.

In December 2024, the Church added Steven Donziger, a Harvard Law graduate, to their running list of honorees. Donziger represented Indigenous and rural communities in Ecuador in a successful case against the energy corporation Chevron for deliberately dumping toxic waste into the Amazon. Chevron retaliated against Donziger, who has faced counter-litigation and criminal contempt of court charges.

“As a younger man, I studied Sacco and Vanzetti, and I’m so familiar with the case and with their history. To be the recipient of an award in their name is quite the honor,” Donziger says, joining the ceremony by Zoom from the NYC apartment where he was under house arrest from 2019 to 2022.

“I also want to accept it really in the name of the Amazon communities of Ecuador,” he adds.

Those communities, however, have reportedly never received a cent of the $9.5 billion in damages Chevron owes to them.

The Community Church of Boston live-streamed the conferral of the award to their 73,700 YouTube subscribers. The ceremony started and ended with two men playing socially-conscious folk ballads on acoustic guitar, which carried tinnily through their computer microphones.

Two months later, I attended my first of the Church’s weekly Sunday services. There, I asked two members if “political martyrdom” is a criterion to be selected for the Sacco-Vanzetti Award. The men agreed.

Afterlives

Outside this Boston-based circle of memory keepers, a wider cultural fascination with Sacco and Vanzetti remains. The men are immortalized in songs by Joan Baez and Pete Seeger, a set of ballads by Woody Guthrie, a book by Upton Sinclair, lectures and writings by historian Howard Zinn — and even an extended post on X by Colombian President Gustavo Petro.

“I confess that Sacco and Vanzetti, who have my blood, in the history of the U.S., are memorable and I follow them,” Petro wrote, just after announcing his temporary ban of U.S. deportation planes seeking to land in Colombia. “They were murdered for being labor leaders with the electric chair by the fascists who are inside the U.S. just as they are in my country.”

Though present in the public consciousness, the Commemoration Society argues that the memory of Sacco and Vanzetti is not consistently manifest in Boston’s public memory, nor in its streets.

The Charlestown Prison where Sacco and Vanzetti were executed — while a massive crowd protested at the doors outside — closed those doors in 1955. Bunker Hill Community College now stands in its place.

A popular rumor circulates there that the college president’s office is exactly where the execution chamber stood, Kaplan says. He and the Commemoration Society scoured the blueprints, proving that this could not be true.

Kaplan recounts this anecdote while holding up, without explanation, a large plastic bag with a small wooden shard.

It’s a piece of the electric chair that killed Sacco and Vanzetti, he finally reveals.

***

At the special reading room of the Boston Public Library, it’s just me and Sacco and Vanzetti. The plaster molds of their faces — their death masks — seem to stare up at me from the table, but their eyes are closed, as though frozen in sleep.

The death masks are part of the BPL’s existing collection on Sacco and Vanzetti, donated by Aldino Felicani. But the collection does not merely include replicas of their remains. The BPL also possesses a single urn containing both Sacco’s and Vanzetti’s ashes mixed together. The rest of their ashes were repatriated to separate parts of Italy.

For the past few months, Kaplan has been in conversation with the BPL to acquire parts of his carefully curated archive. The BPL did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

When I went to the BPL that day, the librarians were abuzz that someone had requested to view the Sacco and Vanzetti death masks. It was their first time viewing them, too, and we ogled together as one librarian opened the box, revealing their impeccably conserved images, enshrouded in plush, kingly purple silk.

Sacco and Vanzetti look back at me through time. All these years later, I am not sure what I am supposed to see in their faces.

— Magazine writer Olivia G. Pasquerella can be reached at olivia.pasquerella@thecrimson.com. Follow them on Twitter @pasqapasqa.

Valerio Pepe ’26 provided Italian translations of archival materials.