News

Nearly 200 Harvard Affiliates Rally on Widener Steps To Protest Arrest of Columbia Student

News

CPS Will Increase Staffing At Schools Receiving Kennedy-Longfellow Students

News

‘Feels Like Christmas’: Freshmen Revel in Annual Housing Day Festivities

News

Susan Wolf Delivers 2025 Mala Soloman Kamm Lecture in Ethics

News

Harvard Law School Students Pass Referendum Urging University To Divest From Israel

Harvard Has an Optimization Epidemic

Harvard students have to stop treating life like an optimization problem.

While wringing every drop of productivity out of our day is the Harvard norm, efficiency can be taken too far. From cramming productivity into each moment to overanalyzing leisure, Harvard students employ a mindset that fuels burnout and detachment. Unfortunately, true fulfillment isn’t something you can optimize.

Last semester, I took Economics 10A: “Principles of Economics,” Harvard’s famed intro to microeconomics and the theoretical incubator of Harvard’s most successful graduates. One course later, I still have no plans of concentrating in Economics, but one of the key concepts introduced on the first day of class has stuck with me: optimization.

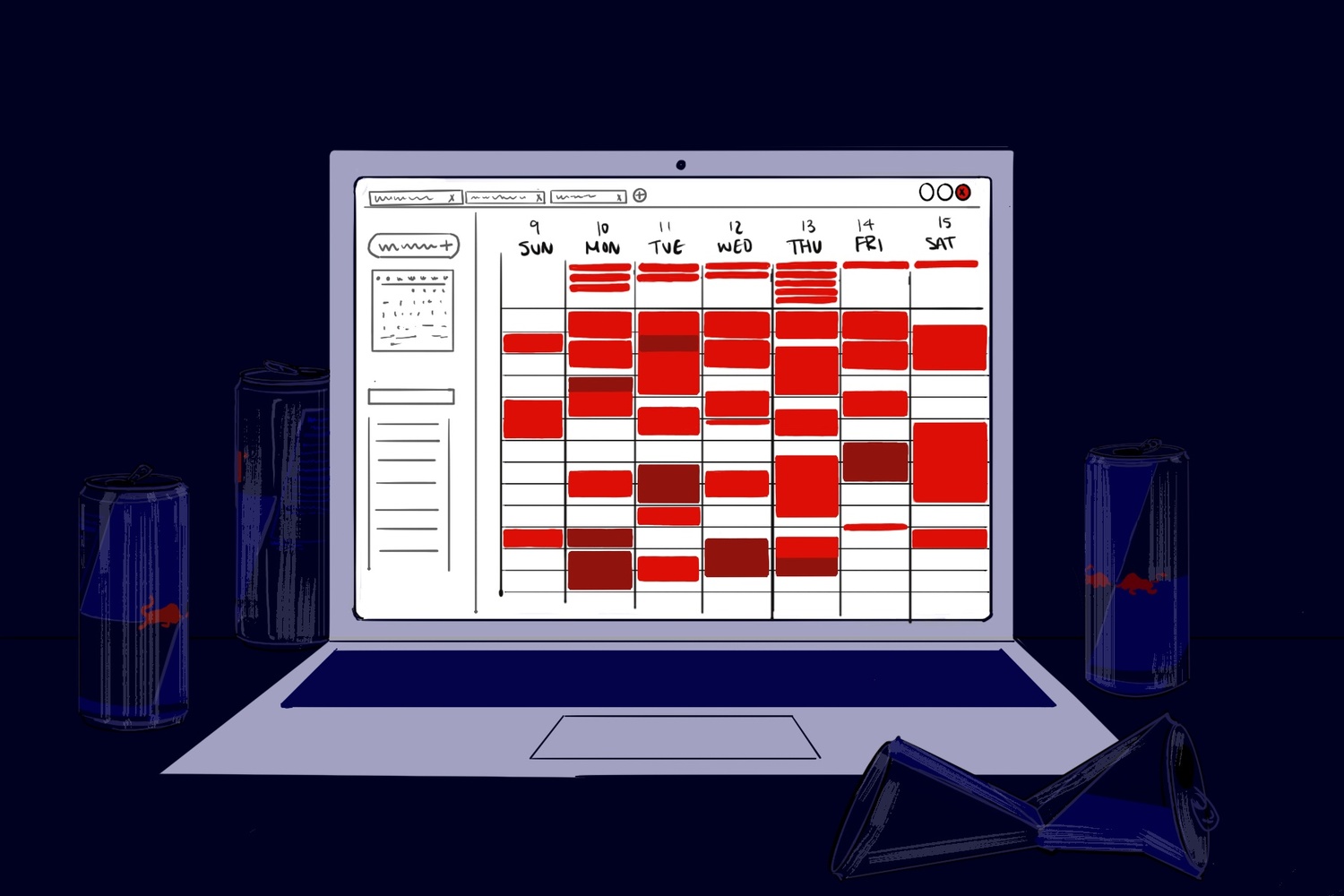

In many ways, optimization describes the dominant ethos of campus culture. We’re stressed. Our GCals are overflowing. No one is getting enough sleep. These are common refrains, and none of them are hot takes. But I would argue they are not only the product of Harvard’s workload, but of how we approach it.

The symptoms of the productivity epidemic are everywhere.

In my classes where computers are allowed, I see students writing emails, doing work for other classes, and yes, on LinkedIn (lest we forget, we’re in the midst of summer application season). Step into almost any lecture hall, and you’ll witness the same behavior. Meanwhile, in the nearest dining hall, chances are there’s at least one student mechanically lifting HUDS chicken into their mouth while staring at their screen.

The constant work culture goes beyond academics. Harvard students valorize work of all forms: p-setting and paper writing, but also going to the gym and minimizing time in lecture with Panopto’s 2x speed feature.

Free time is also affected. Often, when deciding what book to read or movie or show to watch, I catch myself asking what would be the best use of my time. I used to think this particular form of optimization was a personal quirk, but I’ve discovered many of my friends here think similarly.

Even grab-a-meal culture, in which I frequently partake, aligns with the ethos of optimization. Eating is unavoidable — socializing is optional. Thankfully, it isn’t too difficult to do both. Getting a thirty minute lunch with someone kills two birds with one stone.

I’ve found our campus is overrun by this toxic productivity — the pressure to be productive at all times, even at the expense of one’s well being. But isn’t being more productive a good thing? On a personal level, I’m not convinced.

When I go to bed after a long day, I feel accomplished. But I question if that satisfaction is genuine fulfillment or merely a socialized response in a school culture that values constant work.

Optimization is tantalizing. It promises good grades, a full resume, the façade of a successful life. But in the long run, even optimization has its costs. Summarizing a reading with ChatGPT removes the struggle of comprehending it — a struggle crucial to learning. Watching a lecture asynchronously rather than attending in-person drains meaningful connection out of a course. Foregoing lunch with a friend for a takeout box leads, over time, to a weakened support system.

All of this to say that we are too consumed by optimization. We appear to have an unceasing desire to suck the marrow out of every second, of every minute, of every day. I don’t think I’ve felt fully relaxed since before college began. There is always, ostensibly, something I could be working on.

This can’t be the best way to live.

So this semester, try to let yourself breathe a bit. Notice when you feel the urge to continuously “do,” and combat it. After all, there is an opportunity cost to optimization — enjoying your life.

Heidi S. Enger ’27, an Associate Editorial Editor, is a Social Studies Concentrator in Eliot House. She’s enrolled in Ec10b this semester (don’t ask).

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.