News

When Professors Speak Out, Some Students Stay Quiet. Can Harvard Keep Everyone Talking?

News

Allston Residents, Elected Officials Ask for More Benefits from Harvard’s 10-Year Plan

News

Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin Warns of Federal Data Misuse at IOP Forum

News

Woman Rescued from Freezing Charles River, Transported to Hospital with Serious Injuries

News

Harvard Researchers Develop New Technology to Map Neural Connections

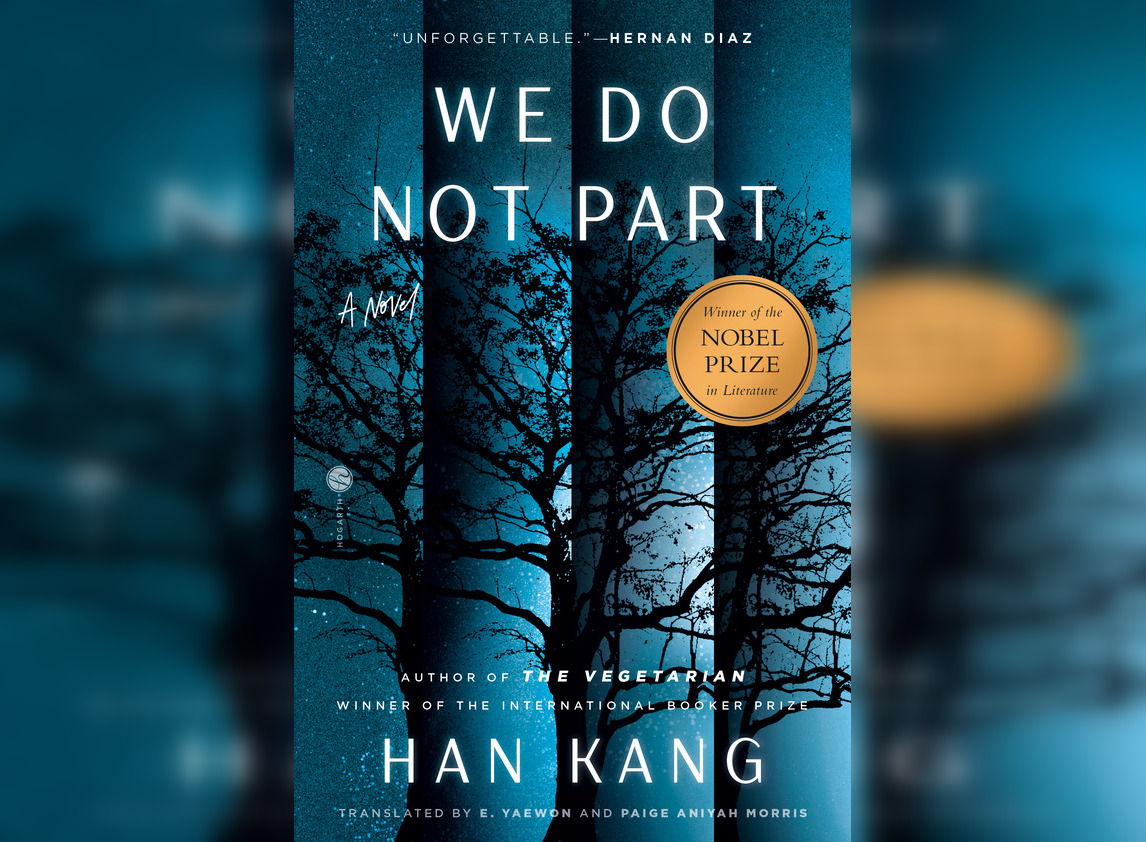

‘We Do Not Part’ Review: Brutality and Beauty

5 Stars

Literature is so back. Han Kang, the recipient of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature and the first Korean author to win the prize, has returned with the novel “We Do Not Part.” First published in Korean in 2021 and translated into English by e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris this year, the book follows writer and protagonist Kyungha when her documentarist-turned-carpenter friend Inseon, undergoing emergency treatment for a hand injury, asks her for a favor: to travel to Inseon’s remote home on Jeju Island to feed her pet bird. Holed up in Inseon’s house during a dangerous winter, Kyungha finds herself haunted by her friend’s family history — a story of political violence, unresolved grief, and seeking truth.

At the heart of “We Do Not Part” lies a narrative about the Bodo League massacre, a series of mass executions of alleged communist sympathizers that the South Korean government carried out in 1950. According to some estimates, up to 200,000 Koreans — some of them children — were killed. In the novel, the family members of Inseon’s mother were among those detained and murdered — a story that reveals itself slowly as a ghostly apparition of Inseon, upon meeting Kyungha in her house, provides her own narration.

Han is no stranger to exploring the legacy of mass murder, having written about the 1980 Gwangju massacre in the novel “Human Acts,” which she considers to be of a “pair” with her latest book. Echoes of “Human Acts” linger throughout “We Do Not Part,” most notably in the fact that Han repeatedly declines to recount history in a conventional way. Stories of the massacre are filtered through multiple layers of telling — for instance, Inseon telling Kyungha the stories that her mother told her.

The prose in “We Do Not Part” is ghostlike, moving freely between voices and timelines. The perspective shifts between Kyungha’s narration and Inseon’s storytelling, while the plot itself progresses non-chronologically through scenes of historical events, flashbacks showing the two women’s friendship, and the novel’s present-day narrative.

“We Do Not Part” is unconcerned with reproducing reality — when Inseon appears in the house with an impossibly unharmed hand, readers aren’t supposed to ask, “What’s really going on here?” Instead, the book leads the reader through a narrative that, real or not, grasps at the story’s emotional truth. This lack of explanation could have been frustrating in the hands of a less capable author, but Kang’s storytelling is so immersive that the novel’s internal logic becomes the last thing on a reader’s mind. More explanation would have, in fact, lessened the story’s dreamlike quality.

Instead, “We Do Not Part” drops the reader into a remote Jeju village in the middle of winter. It might not seem like praise to say that a novel’s most impressive aspect is its description of the weather, but Han depicts Kyungha’s perilous journey through a winter storm with simultaneous ferocity and beauty in an astonishing display of writerly skill. As Kyungha struggles through freezing winds and punishing cold to reach Inseon’s house, the descriptive prose heightens the intensity of a setting that is already well-matched to the story taking place within it. “Everything I have ever experienced is made crystalline,” Kyungha narrates. “Nothing hurts anymore.”

Just as impressive is e. and Morris’s translation. Their work is unobtrusive and restrained, providing context where necessary and preserving Korean words and dialect when called for.

The novel’s dreamlike atmosphere dissipates in its third act, which pulls back from the book’s previous reality-bending style to give a more straightforward retelling of history. While this makes the story less immersive, the shift to a more direct account is arguably needed to drive home the horrific nature of the events described in the novel. The book returns to form in the final section, “Flame,” which closes the novel with its characteristic surrealism, imagery, and expressive prose.

“We Do Not Part” is also a novel that questions how to make art about historical atrocities. Like Han herself, Kyungha and Inseon are artists whose work deals with real-life instances of mass violence. Snippets of documentaries and Kyungha’s own book pepper the narrative; the novel’s emphasis on descriptive imagery means that reading it often feels like looking at a photograph. “We Do Not Part” offers up art as a medium for truth-telling — for imparting the stories of the dead in a way that is, like a winter storm, both brutal and beautiful.

—Staff writer Samantha H. Chung can be reached at samantha.chung@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X @samhchung.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.