News

Harvard Grad Union Agrees To Bargain Without Ground Rules

News

Harvard Chabad Petitions to Change City Zoning Laws

News

Kestenbaum Files Opposition to Harvard’s Request for Documents

News

Harvard Agrees to a 1-Year $6 Million PILOT Agreement With the City of Cambridge

News

HUA Election Will Feature No Referenda or Survey Questions

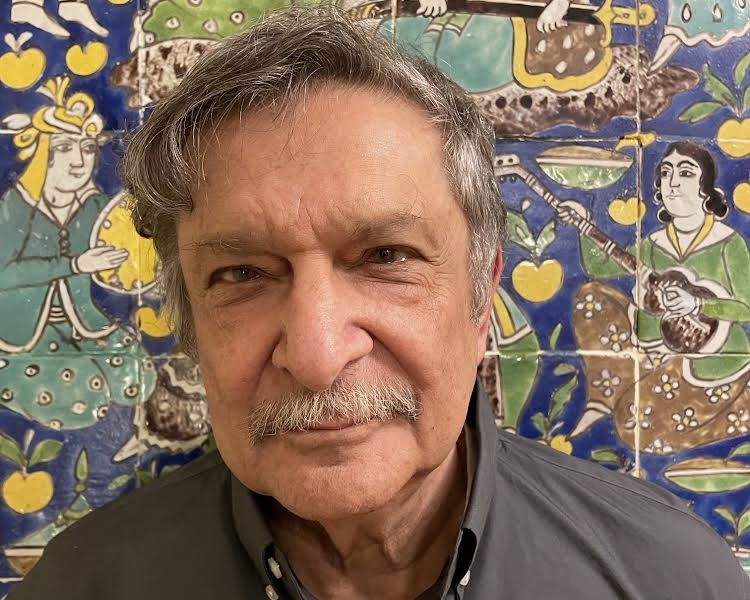

Roy Mottahedeh ’60, Pioneering Middle East Scholar Who Sought to Bridge U.S.-Iran Divide, Dies at 84

As an undergraduate at Harvard, Roy W. P. Mottahedeh ’60 had two tasks to get done one day: return a reserved book to Lamont Library and mail a letter to his parents.

Mottahedeh, though, dropped the book in the mailbox and handed the letter to the librarian.

Realizing his mistake, he rushed to the mailbox and waited for the postman, knowing he was accumulating fines by the minute. When the postman arrived, Roy pleaded for the book back, but the postman refused, saying, “I’m sorry, this book is now the property of the U.S. government.” Eventually, after even more begging, Mottahedeh got the book back.

Mottahedeh, who would later become one of the world’s top scholars on Iran and the Middle East, told his students that he “realized then that there weren’t so many things he could do for a living and he better become a professor,” said Abigail Balbale, one of his former students and research assistants.

After graduating from Harvard, he would go on to earn a second undergraduate degree from the University of Cambridge before returning to Harvard for his Ph.D., where he studied with leading Middle Eastern studies scholars Richard N. Frye — a founder of Harvard’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies — and Sir Hamilton A. R. Gibb.

After 16 years teaching at Princeton, Mottahedeh returned once again to Harvard in 1986 — this time as a professor. He directed the Center for Middle Eastern Studies from 1987 to 1990 and later helped found the University’s Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Islamic Studies Program in 2006.

Mottahedeh died on July 30 at the age of 84.

He is survived by his wife Patricia Mottahedeh, two sons, Rafi Mottahedeh and Rostam Mottahedeh, and a granddaughter, Deirdre.

‘Seemed Otherworldly’

Mottahedeh’s students remembered him as a deeply intelligent and dedicated — if at times absent-minded — professor.

“He had this incredible, incredible brain, but it was occupied with all of these big questions — and everyday life stuff fell by the wayside,” said Balbale, now an assistant professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies at New York University.

“This incredible man who wrote these amazing books could not type. He typed one finger at a time, extremely slowly,” Balbale said. “So one of my tasks as a research assistant was to sit next to him and have him dictate responses to me as I went through his emails.”

However, when it came to her work, Roy would meticulously write long notes in her binder, offering “extraordinary feedback.”

Beyond his work as a professor, Mottahedeh loved books — turning the attic of his home into a library — and Islamic ceramics, a passion he inherited from his parents who were prominent porcelain collectors and traders.

“Because there were so many thousands of books, he had to install a fire sprinkler system in the attic to maintain code. So he had an actual library, with stacks and fire sprinklers, in his house,” Balbale said.

The first time Balbale visited Mottahedeh’s house, she was also struck by what was in his kitchen – a sand table where Mottahedeh meticulously repaired medieval Islamic ceramics he collected.

“He had set up this whole state-of-the-art restoration system in his own house and would buy and restore medieval Islamic ceramics and then display them," Balbale said.

Mottahedeh’s colleagues and former students also praised Mottahedeh as a “gentle” supervisor with an astonishing depth of knowledge about his field of study.

As a Harvard alum himself, Mottahedeh always maintained an “affinity” with Harvard and its students, according to Cemal Kafadar, a History professor at Harvard and the current CMES director.

“He always took undergraduate teaching seriously,” Kafadar said. “He would never raise his voice or anything. He would never rush anybody. Gentle. He almost always seemed otherworldly.”

According to Mottahedeh’s former student Rubina Salikuddin, Mottahedeh could “recall hundreds of texts and he could talk about topics and ideas and themes just like it was nothing, which was just fun to kind of sit and talk with him and hear him give his perspective on 10th century Iran or anything.”

Mottahedeh, Salikuddin said, was a “living, breathing trove of information and knowledge.”

In 1981, Mottahedeh was awarded the prestigious MacArthur Genius Grant — a no-strings-attached award now worth $800,000 — as part of its first cohort of recipients.

When he was notified in 1981 that he had won the MacArthur Genius award, he was “initially doubtful such an award existed and called back for confirmation,” according to the CMES website.

“I think he thought it was a prank call or something like that,” said Arafat A. Razzaque, a former student.

His students also remembered him as a dedicated advisor, who would go to great lengths to discuss their work with them.

Han Hsien Liew, one of Mottahedeh’s last Ph.D. students, said that Mottahedeh even once met with him on a Sunday just to go through his work page-by-page.

“I was very touched by it,” Liew said. “I don’t think many professors would agree to meet with you on a weekend to talk about your work.”

Razzaque, who finished his Ph.D. under Mottahedeh in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic, said that Mottahedeh would “read my chapters of the dissertation, and then he would feed it through a scanner with his comments, and then he called me while I was on a walk in Cambridge to talk about it.”

“When you really needed him, he was there for you,” Razzaque added.

‘A Liaison Between Iran and America’

Over the course of his 46-year academic career, Mottahedeh developed a reputation as one of the world’s foremost scholars on Iran and the Middle East, and an author of core texts in the field.

Salikuddin, who said that Mottahedeh was a “major, towering” figure in Iran and Middle East studies, said that “everybody who works in our field would know him, or would have read him, or would have been influenced by him in some way.

His former students point to his pioneering scholarship as a sign of his influence.

Fred M. Donner, who was Mottahedeh’s first Ph.D. student when he was a professor at Princeton, said that Mottahedeh organized a graduate seminar on the social history of the medieval Islamic world during Donner’s second year, “which almost nobody talked about really at that time.”

Donner said that the seminar was “so inspiring” that the department chair at the time, Princeton professor Abraham Udovitch, also decided to attend the class.

When Mottahedeh came to Harvard, he helped create a new home for studying Islamic history in the History department, where previously it had been within the realm of a more “philologically driven department like Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations,” according to Balbale.

Mottahedeh, Balbale said, showed that “you could ask the same kinds of big historical questions of medieval Islamic sources that you ask of more contemporary European or American sources.”

“That was something that had not really been done before,” she added.

From early on in his academic career, Mottahedeh had developed a reputation for rigorous and pioneering scholarship. His first book, Loyalty and Leadership in Early Islamic Society, helped him win the first MacArthur Genius Grant in 1981, just 11 years after starting his career.

By the time he arrived at Harvard in 1986, Mottahedeh had used his MacArthur award to publish his seminal work, The Mantle of the Prophet, focused on the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

Published in 1985, Mottahedeh received wide acclaim for the book — in particular for making it accessible to the general public. Foreign Affairs, the magazine for the Council on Foreign Relations — of which Mottahedeh was a member — called it “one of the top 75 books of the twentieth century.” Four years later, he would be elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

His colleagues and students said that Mottahedeh was especially focused on mending U.S.-Iranian relations, which ruptured after the Revolution.

“He’s someone who I think was very deeply committed to reconciling Iran and the United States,” said Adam A. Sabra ’90, a former student of Mottahedeh. “He wrote numerous editorials in the New York Times and other places about how perhaps the United States and Iran might get past this period of enmity and be reconciled.

Farnaz Fassihi, the United Nations bureau chief for the New York Times who met Mottahedeh while she was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard in 2015, said that he was a “liaison between Iran and America.”

“I think his contribution, from my perspective as a journalist, was at a time that there was great need for contextual information, historical information about Iran,” Fassihi said. “He was in that place and did it really effectively.”

Mottahedeh’s expertise led him to the White House, where then-President Jimmy Carter consulted Mottahedeh during the Iranian hostage crisis, when more than 50 Americans were taken hostage for 444 days after Iranian students seized the U.S. embassy in Tehran.

“President Carter actually had a naive idea that he could somehow reach out to Ayatollah Khomeini and find some kind of common ground because they both were religious men,” Sabra said. “He invited a bunch of scholars, including people from Harvard, such as Roy, to talk to him about that.”

“Although I think Roy was a bit skeptical about Carter’s ideas, he was very much committed to this,” Sabra added.

But despite focusing his scholarly career on the country from which his own father hailed, Mottahedeh was forced to study the nation from afar. A member of the Baha’i faith, Mottahedeh was unable to go to Iran “for many years” because of religious persecution of the Baha’i community, according to Sabra.

“He was fluent in Persian. He knew the culture backwards and forwards in literature,” Sabra said. “He couldn’t go, but he was deeply committed to reconciling the two countries.”

‘The Rare Harvard Professor’

Beyond his scholarship, Mottahedeh was active in developing programs in Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard. As CMES director, Mottahedeh launched the Harvard Middle East and Islamic Review to give academics an opportunity to publish their work. He also helped establish new academic positions at the University.

“Harvard can now boast of a wider, much wider coverage,” Kafadar said.

“He was able to create a program that brought new energy, new colleagues, to cover areas otherwise not covered in the study of the Islamic world, but with the awareness that we still need to do more,” Kafadar added.

Mottahedeh would also be crucial in helping to establish the Islamic Studies Program at Harvard, which launched in 2006 after a $20 million gift the year prior from Saudi royal Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz Al Saud — then the world’s fifth-richest person, who would have the program named after him.

Mottahedeh, who would serve as the program’s founding director, “did this essentially by winning over the prince, the Saudi prince, and persuading him that Harvard was a place where he should endow a program,” Balbale said.

The donation — which Balbale called “an incredible coup” — indicated to her that Mottahedeh, despite his apparent absent-mindedness, “was incredibly capable.”

“Yet he was humble and always diminishing what he was capable of and diminishing what he had done,” Balbale said. “The rare Harvard professor who didn’t want to brag about his accomplishments, and instead always, always tried to minimize them.”

Correction: August 15, 2024

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Roy Mottahedeh met with Han Hsien Liew every Sunday to go through his Ph.D. work. In fact, Mottahedeh met with Liew only once on a Sunday to go over his Ph.D. work.

—Staff writer Adithya V. Madduri can be reached at adithya.madduri@thecrimson.com.

—Staff writer Mandy Zhang can be reached at mandy.zhang@thecrimson.com. Follow her on X @mandyzhang08.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

Related Articles

Most Read

- Harvard Dismisses Leaders of Center for Middle Eastern Studies

- More Than 80 HLS Professors Denounce Trump Admin Attacks on Law Firms in Letter to Students

- 2 Years After Affirmative Action Ruling, Harvard Admits Class of 2029 Without Releasing Data

- Harvard Agrees to a 1-Year $6 Million PILOT Agreement With the City of Cambridge

- FAS Dean Asks Center Directors To Show Compliance With Viewpoint Diversity Guidance