News

News Flash: Memory Shop and Anime Zakka to Open in Harvard Square

News

Harvard Researchers Develop AI-Driven Framework To Study Social Interactions, A Step Forward for Autism Research

News

Harvard Innovation Labs Announces 25 President’s Innovation Challenge Finalists

News

Graduate Student Council To Vote on Meeting Attendance Policy

News

Pop Hits and Politics: At Yardfest, Students Dance to Bedingfield and a Student Band Condemns Trump

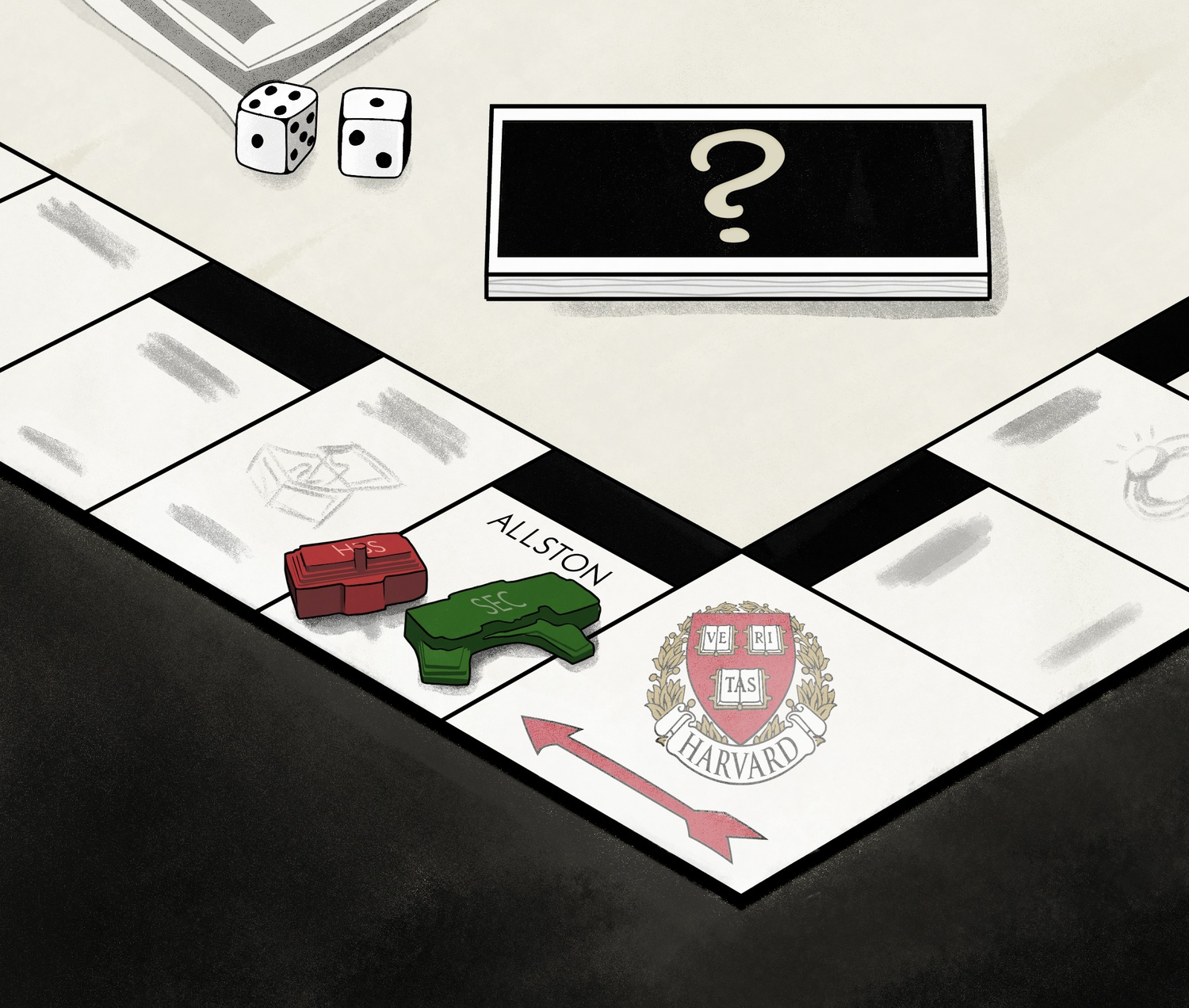

How Harvard Can Build Better in Allston

Harvard is a university — not a general contractor, developer, or local landlord. At least, it should be.

From 1989 through the early aughts, Harvard bought up nearly 200 acres of land in Allston — some of it anonymously, through an inconspicuously-named holding company — with the aim of a 21st-century campus expansion.

Today, Harvard owns about a third of Allston including almost 40 commercial properties in Lower Allston and Brighton. Last week, a Crimson analysis documented that nearly a quarter of those holdings remain vacant, to the dismay of many locals.

As glad beneficiaries of a Harvard education, we support the University’s expansion, which will lead to the creation of cutting-edge new facilities for instruction and research.

But that’s not all Harvard wants. One ambitious development after another, it has become clear that the University designs to remake Allston as it pleases.

A custom-made college neighborhood — it’s a nice idea, on its face. In practice, though, the vacancy problem offers yet another reminder that Harvard does not have Allston’s best interests at heart.

Allston is in the midst of one of the worst housing affordability crises in the country: Between 2011 and 2019, the average home price skyrocketed by 43 percent and median rent surged by 36 percent. During that same period, neighborhood median income shot up by 67 percent, which could suggest an outflow of lower-income Allstonians.

Harvard is only making things worse. By clearing the way for the development of pricey new apartments with insufficient affordable units and letting properties lie vacant, the University makes clear that its goals in Allston begin with a dollar sign.

If Harvard doesn’t change course, it risks losing Allston’s local character by pricing out long-time residents and neighborhood businesses alike. To avert a soulless, glass-and-steel Allston populated by Soul Cycles and Sweetgreens, the University must work in true partnership with the community.

That starts with open engagement. Since its original plans for the neighborhood were shelved after the ’08 recession, Harvard has announced plans for specific projects but failed to fully articulate its vision and aims for the area as a whole.

As a result, when locals have been consulted, it has largely been incremental — scribbles on the margins of the University’s plans. Instead, we envision a process of genuine collaboration that empowers Allstonians to tell Harvard what they’d like to see built in the first place.

Still, input is only a first step. Meaningful change requires investment.

Harvard should commit to keeping space for locals by substantially expanding efforts to build and maintain affordable housing in Allston and by prioritizing local business over corporate chains.

Additionally, the University should build on initiatives like the Harvard Ed Portal, open access to new facilities, and invest in local schools to ensure that its affiliates are not the only beneficiaries of new educational opportunities in Allston.

Harvard takes pride in its preeminence. So long as it remains in the development business, it had better strive for similar excellence.

This staff editorial solely represents the majority view of The Crimson Editorial Board. It is the product of discussions at regular Editorial Board meetings. In order to ensure the impartiality of our journalism, Crimson editors who choose to opine and vote at these meetings are not involved in the reporting of articles on similar topics.

Have a suggestion, question, or concern for The Crimson Editorial Board? Click here.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

Where you should have gotten your protein since 1998.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

HUSL seeks to create and empower a community of students who are seeking pathways into the Sports Business Industry.