News

Harvard Grad Union Agrees To Bargain Without Ground Rules

News

Harvard Chabad Petitions to Change City Zoning Laws

News

Kestenbaum Files Opposition to Harvard’s Request for Documents

News

Harvard Agrees to a 1-Year $6 Million PILOT Agreement With the City of Cambridge

News

HUA Election Will Feature No Referenda or Survey Questions

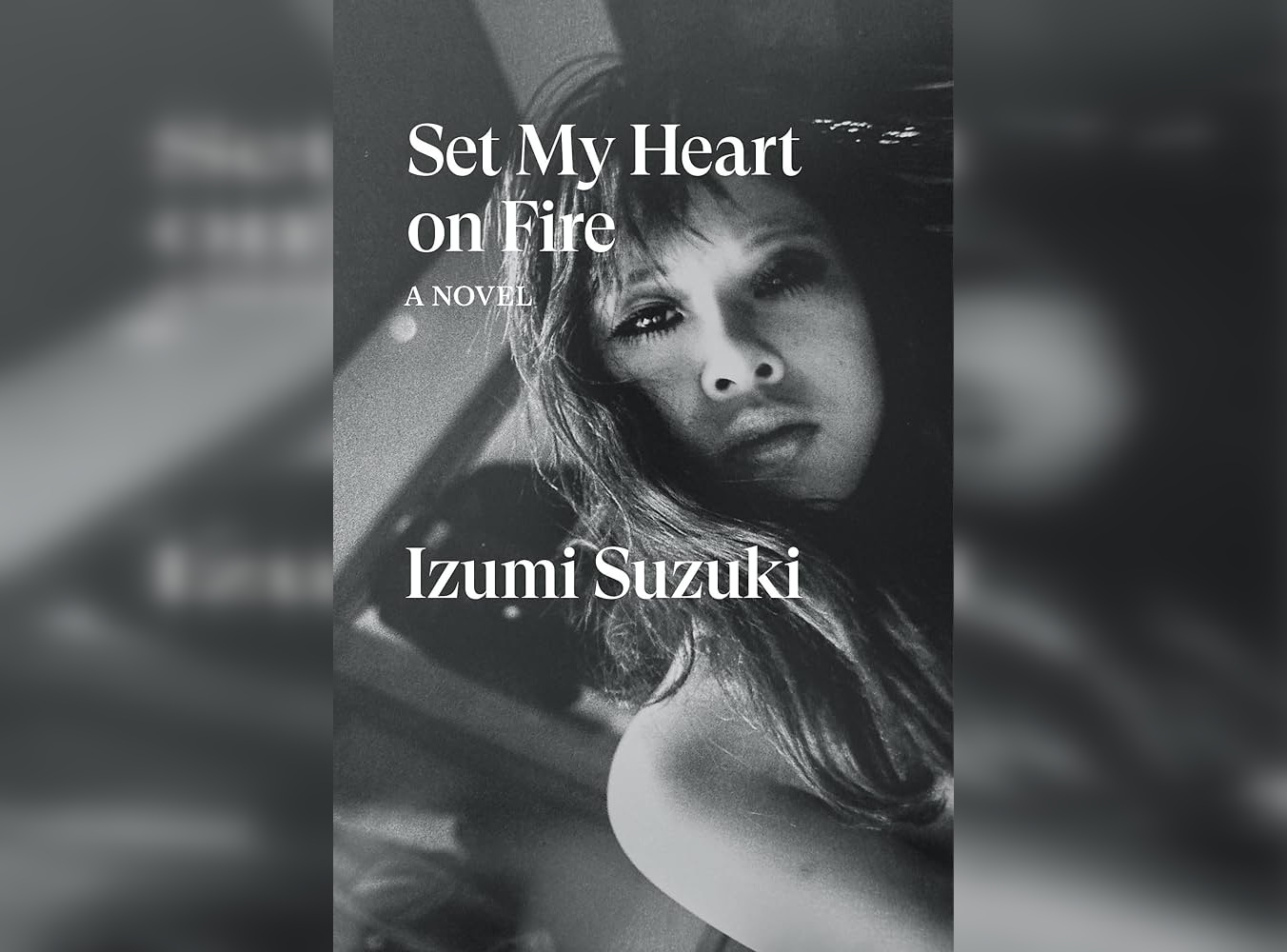

‘Set My Heart on Fire’ Review: A Woman’s Broken Relationship with Addiction, Youth, and the World

4.5 Stars

“It’s a sad story,” states a character at the end of “Set My Heart on Fire,” Izumi Suzuki’s first novel to be translated into English. Known for her science fiction, Suzuki switches genres to tell the story of a young woman navigating the hookup, drug, and rock scene of 1970s Japan. Although not explicitly autobiographical, Suzuki and the protagonist share enough in common — a first name, being ex-models turned writers, marriage to a Japanese free saxophonist — to raise the question of how much Suzuki herself seeps into Izumi’s detached musings. This question is especially pertinent to Izumi’s thoughts on addiction and youth, which are the main driving force in a novel with a sparse plot.

The novel follows Izumi’s life over the course of a decade — from 23 years old to her mid-30s — though very little actually happens in the first half of the novel. In the tradition of the Japanese I-novel, Izumi leads readers in first-person through her sexual conquests with rock artists and her feeling of being a misfit. Her impartiality towards everything lasts until she meets Jun, thus starting a relationship that cleaves her life into a distinct before and an after. It is only after Jun that Izumi fully understands her attachment to her carefree youth as well as her fixation on what it means to be past one’s “golden era.” This lost time looks like a town going into decline, a band passing peak popularity, a woman letting go of her youth.

The musical aspect of the novel comes naturally as Suzuki seamlessly eases readers into it. She manages this by slipping in the name of a band or song playing in the background of a scene, or by including lyrical metaphors, such as Izumi running “at a different tempo” to her lovers and describing the repetitiveness of a night as if “an echo-chamber effect pedal had been plugged into time.” Suzuki even subtly notes the condition of a continually westernizing and modernizing Japan by having Izumi mention the influence of overseas rock icons on Japanese music, the American military base in Japan, and the rise of bustling shopping districts.

Something that could be smoother, however, is the temporal transition between vignettes. Although the vignettes are arranged chronologically, the time jumps between them are inconsistent, ranging from as short as several weeks to as long as several years. The omission of the exact time passed is a bit disorienting, forcing readers to filter through characters’ conversations and Izumi’s internal monologue to fill themselves in on the current situation, as well as events that were passed over in the time jump.

In her narration, Izumi is delightfully contradictory as a self-aware narcissist harboring a deep self-loathing. At times, however, her inner thoughts come across as overly direct, to the point that it nearly becomes awkward to read. Both her highs — “There’s no one else in the world like me” — and her lows — “Who could be honest with a monstrous woman like me?” — stick out as peculiarly pointed and on-the-nose in the midst of Izumi’s otherwise nonchalant tone.

There are also moments where Izumi’s narration borders on metafictional; she feels so detached from her life it is as if she is “watching everything from a slight distance… It’s just like watching a film.” At another point, Izumi uses literary terminology to describe her life’s trajectory, claiming there is “no consistent overarching storyline,” and that she “just is not a protagonist.” Her self-awareness adds another dimension to her that calls for readers’ sympathy towards her situation. When conversing with a friend about her own resigned acceptance of events and indifference towards their outcomes, Izumi recalls the moment she realized that nothing she did could change the world she was born into — a world “created for [her] and it resembled a bad dream.”

Suzuki maintains Izumi’s appeal to readers by balancing out her hopelessness and pessimism with a determination to make the best of a “broken” world. Izumi’s belief that, “in an incoherent, inconsistent world, some exorbitant happiness could always come along” sheds a new light on her thrill-seeking lifestyle: the men, music, and pills she goes through are not just reckless choices but desperate attempts to hang on to life.

As the novel progresses and Izumi ages, the men of her youth transition from sexual escapades to representative figures of the different eras of Izumi’s youth. Izumi describes the man at the focus of her decade-long obsession as “the symbol of a vanished time,” of which she “couldn’t let it go.” Observing Izumi’s change from letting “everything pass” to belatedly realizing she may not want to let go is the core of Suzuki’s poignantly-written piece on a woman forced to outgrow her youth.

—Staff writer Nicole L. Guo can be reached at nicole.guo@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

With innovative financial tools combined with financial education, Collegiate empowers students to take control of their finances and build confidence in their money management skills.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

HUSL seeks to create and empower a community of students who are seeking pathways into the Sports Business Industry.