‘It’s Been Here All Along’: The Effort to Grow Harvard’s Small Language Programs

Harvard offers instruction in dozens of languages from around the world, including small but vibrant programs in Old English, Zulu, and Tagalog. But according to students and faculty, some administrative obstacles often hinder program conception and development.There was no language citation in Uyghur when Kawsar Yasin ’26 arrived on campus in Fall 2022.

The language did have some course offerings at Harvard, though. Yasin — who herself is ethnically Uyghur — decided to enroll in one, and within three years, had laid the foundation for a full-fledged citation in the language.

“It's actually been not too difficult to get it to happen,” Yasin, a Crimson Editorial editor, said. After reaching out to the East Asian Languages and Civilizations department, Yasin had to put together an academic plan with her instructor, Gülnar Eziz, a preceptor in Uyghur and Chaghatay, for how she planned to pursue her citation. After getting the plan approved, Yasin became the first-ever Harvard student to pursue a citation in the language.

Harvard offers instruction in dozens of languages from around the world, including small but vibrant programs in Old English, Zulu, Tagalog, and Uyghur. But according to students and faculty, while the University facilitates the expansion of course offerings, some administrative obstacles often hinder program conception and development.

In interviews with The Crimson, over a dozen Harvard faculty members and students who either teach or study a smaller language highlighted the support that the University provides in helping launch their language program. But they also noted that administrative policies like time caps on non-tenure-track professors and a lack of funding for instruction in languages taught outside of Europe prevent the courses from flourishing.

‘Slow Moving to Change Something’

Language instruction — particularly in smaller, less-spoken languages — has been a part of the Harvard curriculum since the College’s founding, when students at Harvard would take courses in Biblical Hebrew and Arabic, which was first taught at Harvard starting in 1654.

Over the past 150 years, Harvard has continually expanded its course offerings in languages from around the world, beginning instruction in Mandarin in 1879 and Celtic languages in 1896.

Since then, the University has continued to create new courses in other languages as recently as 2023, when Harvard introduced classes in Filipino (Tagalog) and Albanian — becoming the only Ivy League school to teach the Balkan language.

“Students have been asking for this for decades,” said Eleanor V. Wikstrom ’24, a former Crimson Editorial chair who helped launch Harvard’s Filipino (Tagalog) language program last year. After working with the Harvard Club of the Philippines and the Harvard Asia Center to prepare a proposal for language instruction, the University hired its first Tagalog language preceptor after a $2 million donation from Filipino House of Representatives Speaker Martin G. Romualdez.

That same year, Harvard also began teaching courses in Albanian — with three students taking it in the Fall 2024 semester — through its Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations department. The program was developed after lobbying from students, including Edona Cosovic ’25, who worked with administrators in NELC and other students to start the program.

Cosovic, a former Crimson News editor, said that after a year of “logistical issues,” including an initial requirement that the Albanian instructor was at the professor level, “eventually the course was offered despite these difficulties and found a home” in NELC.

Language offerings at Harvard, though, can also be self-designed by faculty members already at the University. Meryem Demir, a preceptor in Turkish, said that when she came to Harvard, she had been interested in teaching both Turkish literature and Turkish language — but the University at the time only offered instruction in the language.

“And it finally happened at Harvard,” Demir said. She created Turkish 130: “Advanced Topics in Turkish Language, Literature, and Culture,” which is currently in its second semester.

“It’s slow moving to change something,” she said, “but it worked.”

Demir also expanded her syllabus by creating the “Zipir Turkish” program, which uses street graffiti to teach the language.

Even for languages that have been offered by the University for a longer period of time, some preceptors said they have flexibility in adapting the curriculum.

Gaia Bencini, a Ph.D. student in NELC who also teaches a course on Egyptian hieroglyphics, says that she was able to create her own syllabus thanks to the support of her supervisor, Anthropology professor Peter Der Manuelian.

Manuelian “believes in us to craft our own kind of syllabus, of course with guidance,” Bencini said.

Sara Feldman, a preceptor in Yiddish, changed the Yiddish course syllabus to make it more gender inclusive and include elements of Hasidic Yiddish.

“In terms of building the curriculum with a small language — nobody knows the faculty who are teaching it and the students who are taking it — nobody knows what’s needed,” Feldman said. “I'm often able to choose a topic that specifically speaks to the interests of the students in the class.”

An Uphill Battle

But many of the smaller language courses often face a series of challenges when it comes to growing the program.

The courses often have enrollment in the single digits, and while many students credit the small size of the class with greater classroom bonding and helping to foster a closer relationship with their instructors, faculty members say that they face an uphill battle when it comes to attracting students.

Céline Debourse, a professor in NELC, believes there is a lack of awareness for small language programs among the student body.

“I think it’s mostly that students really have no clue that some of these languages exist in the first place, and then that you could even study them here,” she said. “That’s the main focus for now — to spread the word that it's here. And it's been here all along.”

Nataliya Shpylova-Saeed, a preceptor in Ukrainian, said that small languages need more visibility.

“We have to justify somehow for the time and effort the students are ready to invest into these languages, because learning any language will take a lot of time,” she said. “It’s very easy for them to be overwhelmed by other languages, which are probably more popular.”

Sasha C. Tunsiricharoengul ’25, a former student in the Thai language program, said that some of the issues with visibility are exacerbated by a lack of separate academic departments. Thai and other Southeast Asian languages are housed in the department of South Asian Studies, potentially limiting their visibility to students interested specifically in Southeast Asian Studies.

“I think accessibility, discoverability could be improved, promoting that there are some other languages that might be logged into bigger departments that you might not know about,” Tunsiricharoengul said.

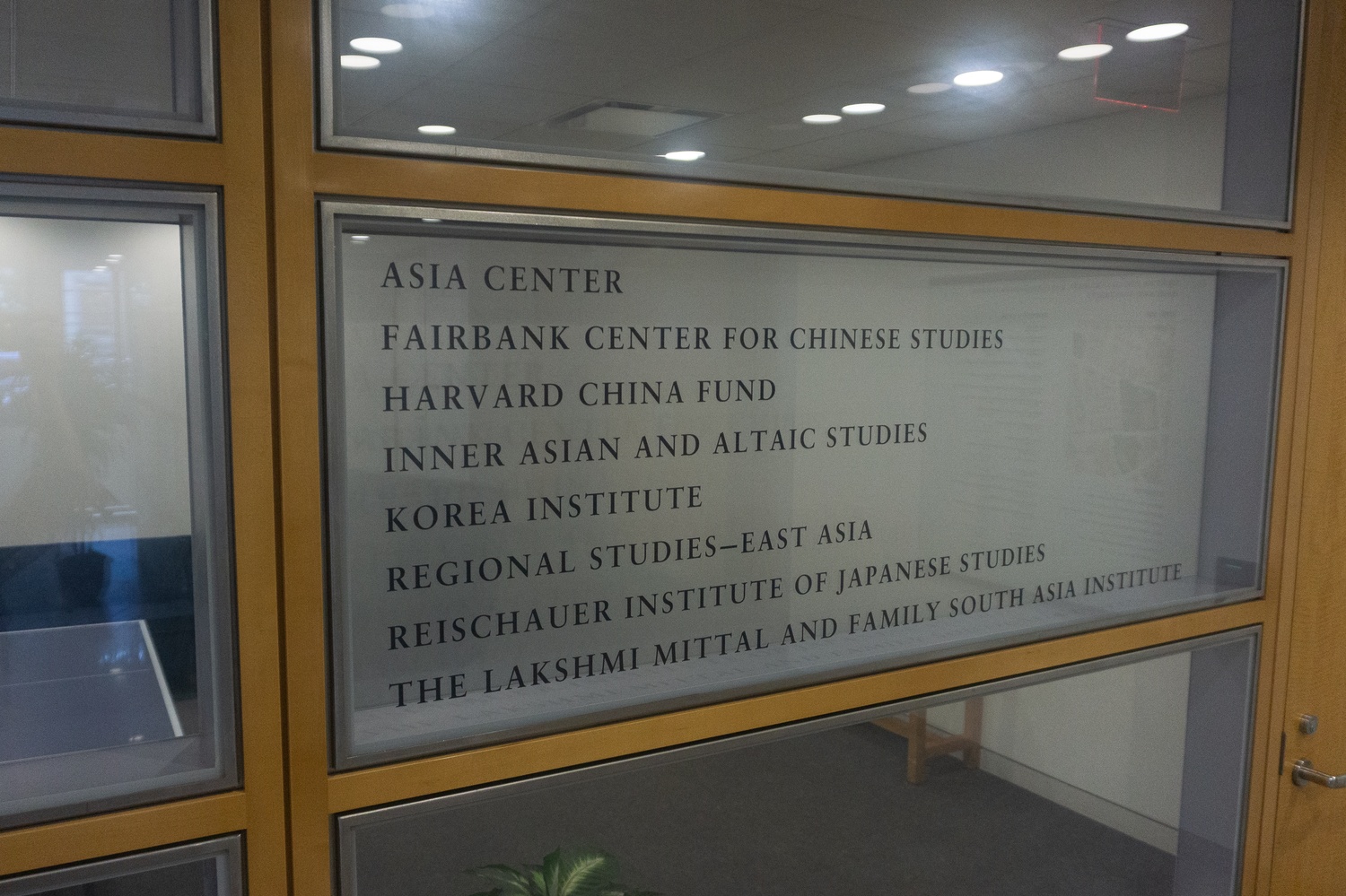

Wikstrom said that the lack of a distinct Southeast Asian Studies department posed a problem when trying to launch the Tagalog language program.

“We have been getting shuffled in between the South Asian and East Asian departments, who would continuously refer us to one another, and then things would kind of go nowhere,” she said, leading her to work with the Asia Center to help develop the course.

Faculty of Arts and Sciences spokesperson James Chisholm declined to comment for this story.

‘Everything’s Going to be Gone’

Additionally, few of the courses are taught by tenured or tenure-track faculty members. Instead, many of Harvard’s smaller language courses are taught by non-tenure-track preceptors, who are subject to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences’ eight-year time cap on employment.

The time cap, according to several faculty members and students, creates serious headaches for the development of courses. Faculty members are forced to cycle out every eight years, preventing the creation of a cohesive course culture and curriculum.

Tunsiricharoengul said that when her Thai instructor had reached her time limit and could no longer teach, it was “really devastating for the students.”

“That whole process of transitioning the one Thai teacher we have at this campus who's been here for a decade just felt like they didn’t care much about their students and what the students wanted,” she said.

Demir, the Turkish language preceptor, said she is not sure what will happen to her course after her time cap hits next year.

“Next year will be my eighth year, and then I don’t know what will happen,” Demir said. “I built the curriculum. I created enthusiasm as much as I did. I invested, like other language faculty,” she said.

Ph.D students that teach languages also face similar concerns, as some programs do not offer postdoctoral positions in the department. Bencini said that she and the other Ph.D. students in her cohort “will have to branch out in other institutions because there’s simply no postdoc position at Harvard.”

Feldman, whose contract will expire in 2026, said that the timecaps hamper the development of language programs. She is one of two Yiddish instructors at Harvard alongside professor Saul Noam Zarrit, who is also set to leave the University after being denied tenure in June.

“If there’s a new instructor every few years then every single time it’s a blank slate with no institutional memory,” Feldman said. Feldman is a leader in the faculty movement to abolish time caps, adding that the instructors themselves are forced to spend less time on their classes because they have to find other jobs.

“The connections that I’ve built, the relationships, the curriculum — everything’s going to be gone, and the next person is going to have learn their way around campus and do it all over again,” Feldman added.

Chisholm, the FAS spokesperson, referred The Crimson to a previous statement on negotiations between the University and Harvard Academic Workers-United Auto Workers, the non-tenure-track faculty union that is calling to abolish time caps.

“We appreciate the Union’s desire to suspend a policy with which it disagrees. The University will not, however, waive long-standing policies as part of a stand-alone proposal before the parties have fully engaged in bargaining and considered the issue of term limits in the full context of this first contract between the parties,” the statement read.

Additionally, some departments which rely on non-tenure-track faculty to teach their language courses are also struggling with hiring tenure-track faculty members in their departments.

“We are struggling because of Harvard administration. They don’t have much touch with reality. We have been asking for professor positions in certain subjects for years and years, and we haven’t been given any,” Hajnalka Kovacs, the Hindi and Urdu preceptor, said.

“As far as I’m concerned, I would like to see more languages, definitely. It’s really not the willingness or unwillingness of the faculty,” she added. “The department has three full-time faculties, and that is not the department’s mistake.”

Other language programs, though, have been able to evade the problem posed by time caps entirely.

Catherine McKenna, a professor of Celtic Languages, said that “by long standing agreement with the administration,” modern Celtic languages are not taught by preceptors, but by graduate students who are not subject to time caps.

Still, faculty in departments where languages are largely taught by preceptors say they are hopeful for the future of language instruction.

“Currently, the EALC department and the History Department is doing a joint search for positions for Professor of Vietnamese History,” Hoa Le, a Senior Preceptor in Vietnamese and the Vietnamese Language Program Director, said.

With the increasing interest in the language program, Le hopes it will continue to expand sustainably.

Kovacs said that she was “optimistic” about the future of South Asian Studies.

“I hope that our language program will continue and I hope that we can do steps to improve it,” she said.

Correction: December 14, 2024

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Harvard is the first Ivy League school to teach Albanian. In fact, Columbia University offered Albanian courses from the 1930s to the 1960s.