News

Harvard Grad Union Agrees To Bargain Without Ground Rules

News

Harvard Chabad Petitions to Change City Zoning Laws

News

Kestenbaum Files Opposition to Harvard’s Request for Documents

News

Harvard Agrees to a 1-Year $6 Million PILOT Agreement With the City of Cambridge

News

HUA Election Will Feature No Referenda or Survey Questions

‘Did You Eat? (밥 먹었니?)’ Review: Emotional Projections

Trigger Warning: This review contains mentions of abuse which may prove uncomfortable for some readers.

Zoë Kim’s autobiographical one-woman play “Did You Eat (밥 먹었니?)” asks a variety of questions: How do we express — and accept — love? What do we owe the people who have hurt us? What do we owe the family who have hurt us? Kim and the rest of the team at CHUANG Stage and Seoulful Productions have created a production that gives a deeply moving, if imperfectly articulated, answer.

“Did You Eat (밥 먹었니?)” covers Kim’s life story, focusing on how she overcame the physical and emotional abuse that her parents inflicted. As the sole actor and writer, Kim embodies her various family members as well as herself at various ages while recounting this narrative to the audience in the second person. In Kim’s speech, the events of her life are framed as events that “will” happen to the audience. This perspective and tense, meant to universalize the experience, instead serves to remind the viewer of the divide between themselves and Kim’s experiences.

Often, the parts of the production that suffered the most were the least descriptive. Particularly at the introduction and conclusion, the script veered into territory that felt more preachy than evocative. On the other hand, when “Did You Eat?” shows instead of telling, the material wrings joy and tears. It is the vivid details of Kim’s childhood and adolescence, more than the prescriptive monologues, that serve to create a rich and interesting portrait of a fascinating artist who overcame incredible adversity.

These anecdotes also provide a much richer platform for the acting capabilities of Kim, dressed in childishly oversized overalls from costume designer Szu-Feng Chen, as she expertly darts in between roles. Aside from playing herself, she swerves between languages and accents to inhibit her father, mother, and grandmothers. Subtle shifts in posture elegantly signal shifts in character without appearing hamfisted.

Chris Yejin’s directing makes good use of the entire stage, as every step feels deeply purposeful. The blocking also seamlessly flows into the more choreographic movements by Christopher Shin. Often, Shin pairs repetition in dialogue with repetitive physical motion. Particular movements, like Kim’s exaggerated kneeling posture to tie her classmates’ shoes, bring humor as well as sympathy for her hunched posture.

While the show’s visual aesthetic sometimes feels confusing, this is not the result of an absence of interesting and appropriate ideas. Rather, it seems to come from too many. The scenic design — also by Szu-Feng Chen — particularly suffers from this overcrowding. Broken plates hanging from the ceiling make sense as a metaphor for the violence inflicted by abuse and the process of recovering a shattered self, but pair strangely with the colorful silk backdrop and multicolored bubbles painted on the floor. These too might seem like an unusual fit for the often heavy subject matter, but often this contrast of childlike design in the set and costume serves to highlight the tragic loss of innocence brought about by negligent and dangerous parents — albeit a strange impression when combined with the harsher moments of choreography.

Meanwhile, an abstract tent of fiery tulle comes to represent the relationship between Kim and her mother, but before that storyline comes to fruition, it just appears unexplainably focal. None of these ideas are bad — in fact, most make a great deal of thematic sense — but their combination confuses rather than enriches.

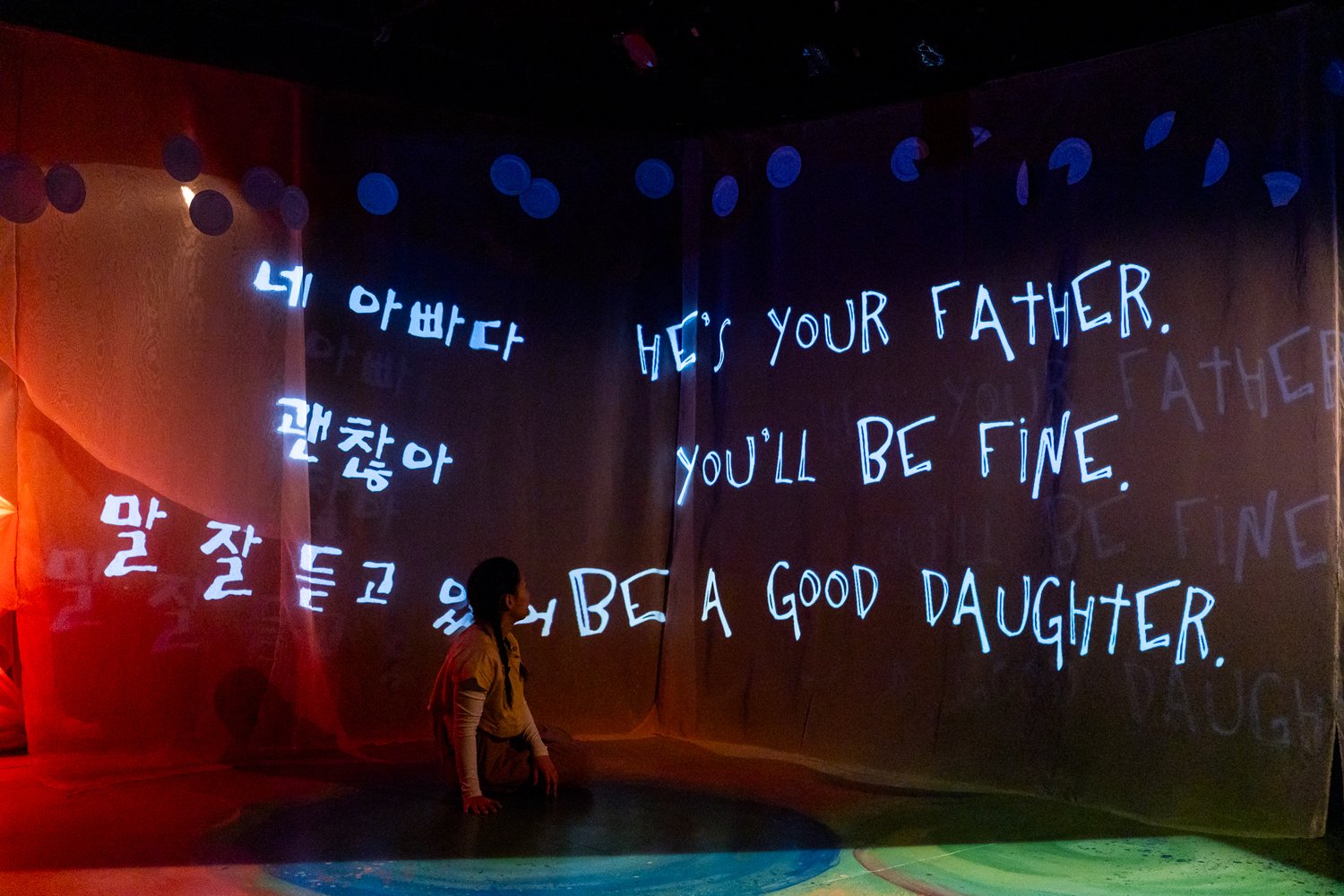

That being said, some of the show’s strongest moments come from the incredible combination of Chen’s scenic design with projection and light work by Michi Zaya and Ari Kim, respectively. The sheer curtain at the back of the stage catches the various projections beautifully while leaving a corridor behind it still visible. At first, the projections primarily enrich the show in the form of live subtitles. Whenever Kim speaks Korean, the translation appears beside her, allowing for seamless audience comprehension.

As the play goes on, the projections help to create some of the best holistic sequences in the show. In one particularly stunning moment, Kim walks through the passageway as words begin to cluster onto the gauzy curtains. This wall of words begins to rain down, pouring onto Kim’s still-visible figure. Moments like this in the play are astonishing — a perfect combination of all the creative elements working in harmony.

It’s the wealth of scenes like this that certainly justify watching “Did You Eat (밥 먹었니?).” Even when the show arrives at its aforementioned preachy conclusion, the palpable earnestness and passion radiating off of everyone who put together this production is enough to love it — despite some growing pains.

“Did You Eat? (밥 먹었니?)” runs at the BCA Plaza Black Box Theatre through Nov. 30.

—Staff writer Ria S. Cuéllar-Koh can be reached at ria.cuellarkoh@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

With innovative financial tools combined with financial education, Collegiate empowers students to take control of their finances and build confidence in their money management skills.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

Admit Expert is a premium MBA admissions consulting company, helping candidates secure admission to top B-schools across the globe with significant scholarships.