News

When Professors Speak Out, Some Students Stay Quiet. Can Harvard Keep Everyone Talking?

News

Allston Residents, Elected Officials Ask for More Benefits from Harvard’s 10-Year Plan

News

Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin Warns of Federal Data Misuse at IOP Forum

News

Woman Rescued from Freezing Charles River, Transported to Hospital with Serious Injuries

News

Harvard Researchers Develop New Technology to Map Neural Connections

Sanitizing Roald Dahl: A Misguided Attempt at Inclusion

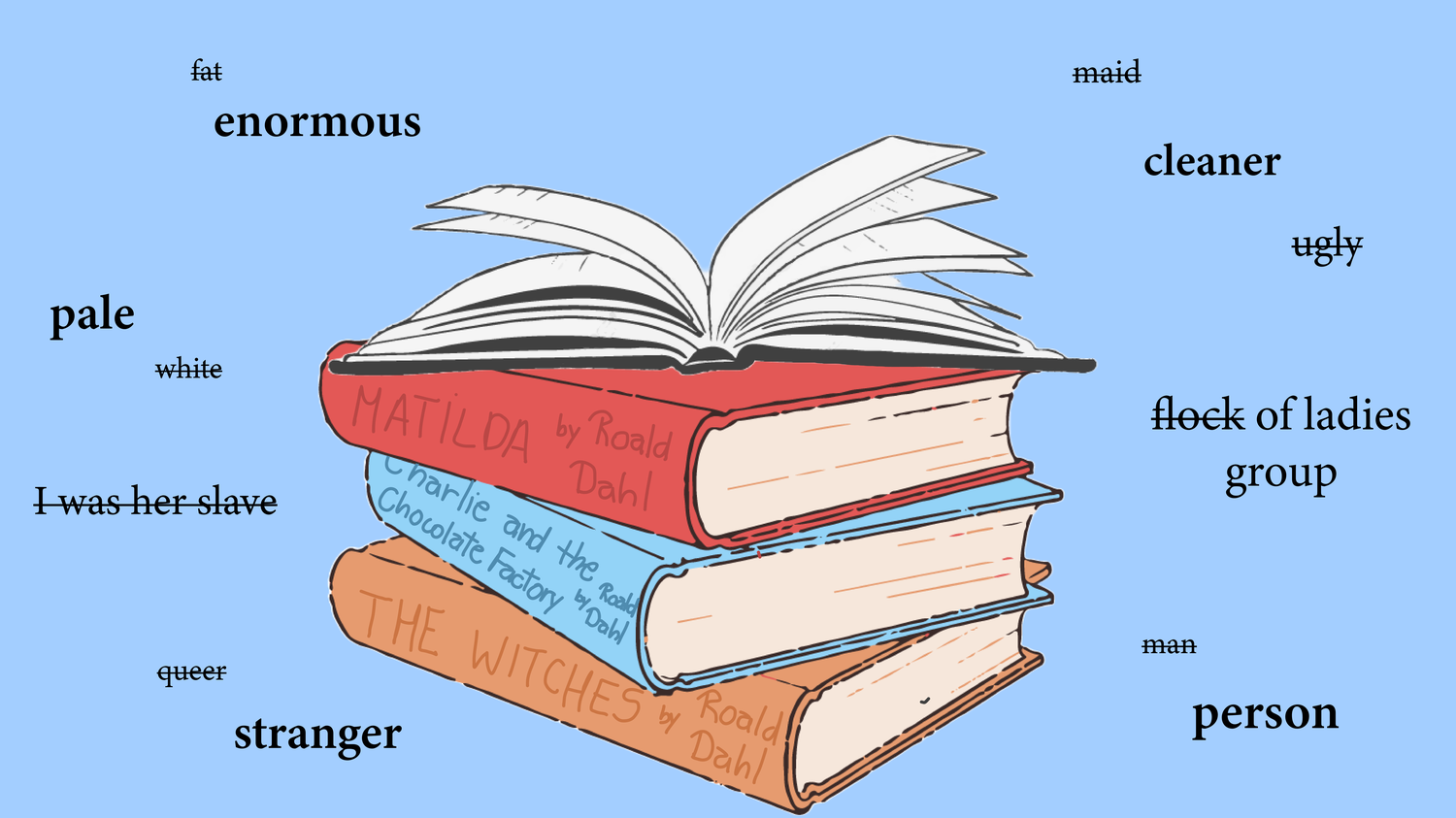

On Feb. 18, Puffin Books announced they would be republishing new editions of Roald Dahl’s books. This is not a surprise: His books have long been famous and influential, with many children growing up reading him, and their relevance continues today — in fact, a new film adaptation of the musical based on his beloved children’s novel “Matilda” was released in cinemas last December. However, these new editions come with a surprising change: The content of Dahl’s books has been edited for inclusion and sensitivity.

In some ways, this could be considered a welcome change. Dahl frequently mocked the physical characteristics of his characters, particularly women, in his novels. Some of the new edits shift away from this reductive language, instead criticizing the behavior and actions of these characters. This included changing the description of Augustus Gloop in “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” from “fat” to “enormous” and replacing the word “female” in “Matilda” to “woman.” Although there is merit to the idea of phasing out reductive language in books being published today, many have opposed this choice, including British PM Rishi Sunak and author Salman Rushdie, who called it “absurd censorship.”

Puffin has defended this decision, saying that they have a responsibility towards young readers, especially when these novels could be some of the first they ever read. Although approximately 100 changes spread across at least a dozen books may not appear to be that concerning, they raise the question of why these edits were even necessary. This debate is reminiscent of the backlash a 2011 republishing of Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” received, in which two racist pejoratives, including the n-word, were removed. Though this sparked discourse about the anti-racist work Twain was attempting to do despite using that slur, and the modern value of this choice, the changes made to Dahl’s work seem incidental in comparison. However, these edits could be in response to deeper issues in Dahl’s novels as they implicitly reference other problematic elements about Dahl’s writing.

Dahl was famously antisemitic during his life, saying that he had “become antisemitic” in a 1990 interview and making comments such as, “There is a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity.” His antisemitism is perhaps most obvious in “The Witches,” a novel about a group of witches who prey on children and try to control the world’s economy through a global conspiracy, all of whom wear wigs and have large noses, and whose physical differences from humans can be spotted if watched closely. His estate made an apology for the hurt caused by his attitudes and comments in 2020; however, the content of this apology was pretty lukewarm.

The apology read: “Those prejudiced remarks are incomprehensible to us and stand in marked contrast to the man we knew and to the values at the heart of Roald Dahl’s stories, which have positively impacted young people for generations.”

Several Jewish groups responded saying this was not good enough, with Marie van der Zyl, president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, saying, “This apology should have happened long ago [...] His abhorrent antisemitic prejudices were no secret and have tarnished his legacy.”

Roland Barthes’s concept of the “death of the author,” or the idea that the intention of an author should be irrelevant when considering their work, particularly applies to this discussion. When creators of art hold harmful and offensive attitudes, people are forced to wonder if they can ethically consume their media. Considering Dahl’s reprehensible views, and the platform these continued republishings bring to his work, this idea is very relevant. But unlike in many other contemporary examples, Dahl died in 1990 and is no longer alive to profit from his works, though his estate itself is alive and well.

It is therefore clear that remnants of some of his more harmful attitudes will still remain in his work, regardless of some in-line edits. Though it is certainly a positive to present children with wonderful literature that is also empowering and uplifting to all readers, it seems misguided to warp Roald Dahl’s novels in pursuit of that aim. There is definitely still value in reading Dahl — his children’s novels are notable for having darker and wackier themes than his contemporaries, and often provide uplifting if unconventional messages — but there would be more value in reading him critically, considering his biases, and helping young readers to think about the perspective of the stories they are being told, instead of haphazardly painting over potentially harmful comments about a character’s appearance.

In response to this backlash, Penguin has decided to also republish the original, unaltered versions of Dahl’s text alongside the updated versions. Though this is a reasonable compromise, it doesn’t make any clearer what the updated versions intended to achieve. It would be much more fruitful to put this kind of time and energy into publishing and republishing living authors, whose original incarnations of their novels are supportive and inclusive and uplifting to children. Trying to rewrite Dahl only has the potential to provide monetary benefits to a select few, and it fails to critically engage with his novels and his bigotry.

—Staff writer Millie Mae Healy can be reached at milliemae.healy@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.