News

Harvard Researchers Develop AI-Driven Framework To Study Social Interactions, A Step Forward for Autism Research

News

Harvard Innovation Labs Announces 25 President’s Innovation Challenge Finalists

News

Graduate Student Council To Vote on Meeting Attendance Policy

News

Pop Hits and Politics: At Yardfest, Students Dance to Bedingfield and a Student Band Condemns Trump

News

Billionaire Investor Gerald Chan Under Scrutiny for Neglect of Historic Harvard Square Theater

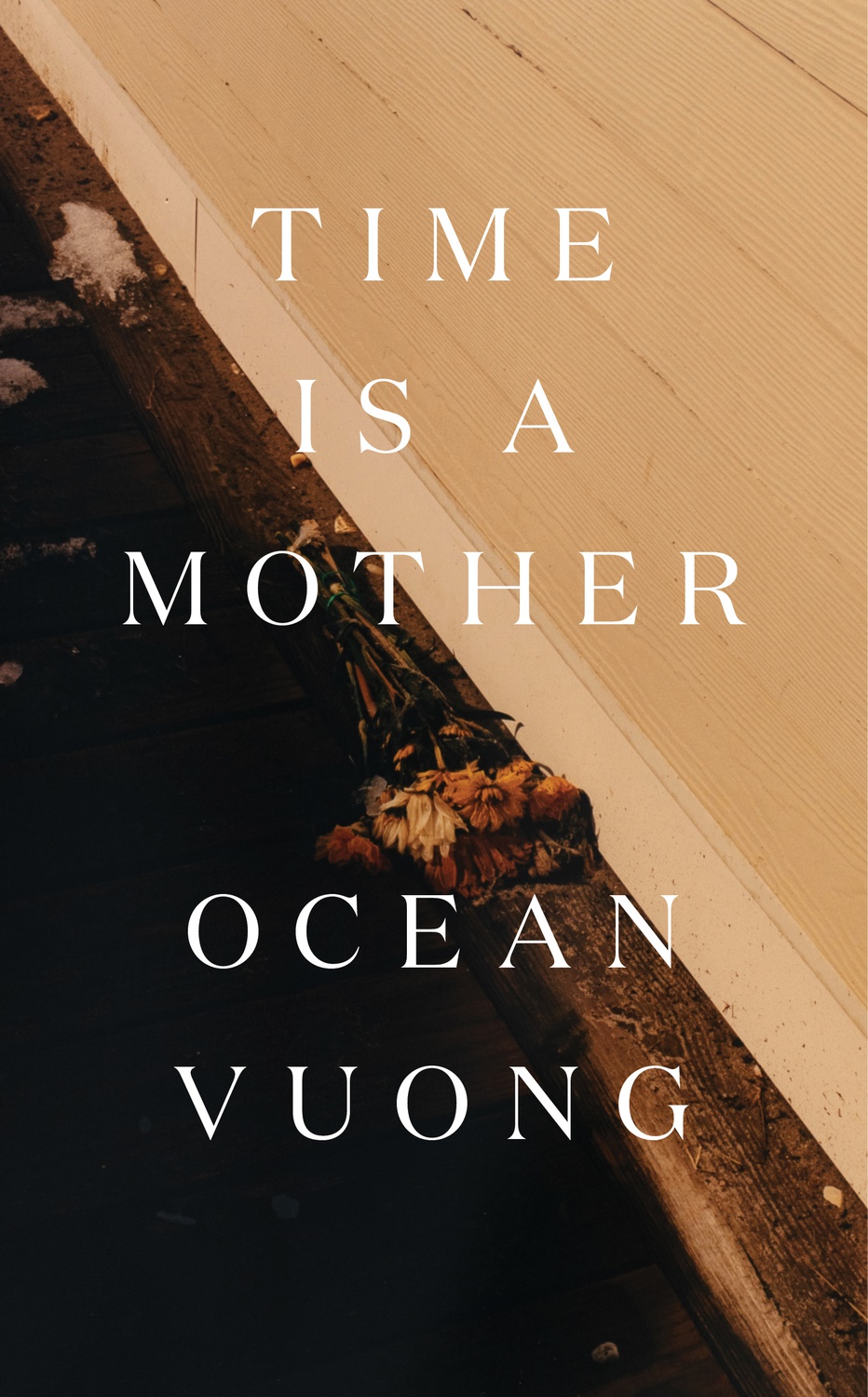

‘Time Is a Mother’ Review: Ocean Vuong Steps Beyond the Edge

4 Stars

Ocean Vuong’s second poetry collection “Time Is a Mother” explores how the passage of time shapes the intimacy of human relationships. At once mournful and celebratory, the collection echoes his past work in its fixation with time. Here, he explores its shifting features — how it is at once violent and protective, effacing and preserving. Poems in the collection such as “Almost Human” and “Not Even,” recall his breakthrough poem “Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong” in the speakers’ interior dialogue with themselves. The prosaic “Nothing” and “Künstlerroman,” filled with ordinary landscapes vitalized by a longing for intimacy, are reminiscent of his sensational debut novel “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous.” Yet Vuong’s writing has also matured. Moments of eruptive joy fragment the wistfulness and melancholy that define his landscapes. Honoring the persistence of grief, Vuong also holds fast to the conviction that something must exist beyond it. Ultimately, “Time Is a Mother” at once preserves and expands the poignant verse readers have come to expect of Vuong.

For Vuong, intimacy and distance are often flipsides of the same coin. Someone with whom he has shared a myriad of experiences swiftly turns inscrutable, and another who has for years been a stranger becomes, in a sudden turn of events, achingly close. Though he draws inspiration from his own lived experiences, the sensation he describes comes across as universal. In “American Legend,” a car accident literally makes two emotionally distant people collide in a startling moment of communion: “I wanted, at last, to feel him / against me—& / it worked.” Vuong continues, “he slammed / into me & / we hugged / for the first time / in decades. It was perfect / & wrong, like money / on fire.”

Indeed, it is in these moments of quiet and electrifying transgression that Vuong’s collection shines. In his prose poem “Nothing,” Vuong’s speaker recalls shoveling snow with a significant other. Precise descriptions of the ethereal landscape brush shoulders against devastating assertions delivered in a jarringly neutral tone: “It’s so quiet every flake on my coat has a life. I used to cry in a genre no one read.” Later, Vuong gives voice to the elusiveness and the paradox of human connection. His description of the expansive multitudes of a single person is markedly Whitmanian: “There is so much room in a person there should be more of us in here. Traveler who is inches away but never here, are you warm where you are?”

Arguably the most memorable poem is the last one in the entire collection, “Woodworking at the End of the World.” Its introduction is faithful to the understated, piercing drama that has come to characterize Vuong’s verse: “In a field, after everything, a streetlamp / shining on a patch of grass. / Having just come to life, I lay down under its warmth / & waited for a way.” In the poem, the speaker meets a boy, presumably their younger self. The brief exchange Vuong has with the boy at the end of the world is mythic, verging on a parable: “he kissed me as if returning a porcelain shard / to my cheek. / Shaking, I turned to him. I turned / & found, crumpled on the grass, the faded red shirt.” The boy, like so many of the other people that populate Vuong’s pages, is at once estranged and intimate, inscrutable and strikingly familiar. His simple yet gorgeous language illuminates the enduring bond between the speaker and the boy, building toward an apt climax for both the poem and the collection at large.

Ultimately, Vuong’s newest collection is, quite literally, full of fear. Different fears mingle, coalesce: a fear of loss. A fear of estrangement and, at times, a fear of closeness — or at least the interior truths that closeness reveals about ourselves. A fear of connections that dissipate before they have the opportunity to begin. The lines that cinch “Time Is a Mother” are delivered in a moment of revelatory catharsis: “Then it came to me, my life. & I remembered my life / the way an ax handle, mid-swing, remembers the tree. / & I was free.” The finale of Vuong’s sprawling poetic vision is at once dangerous and peaceful, elegiac and triumphant. Vuong’s text pulses with an attentiveness to fear. It is through this emotion that he renders such luminous meditations on his life, and of the people who have come to change it. Vuong fears, which is to say, he refuses to not love.

—Staff writer Isabella B. Cho can be reached at isabella.cho@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @izbcho.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

Where you should have gotten your protein since 1998.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

HUSL seeks to create and empower a community of students who are seeking pathways into the Sports Business Industry.