News

Harvard Researchers Develop AI-Driven Framework To Study Social Interactions, A Step Forward for Autism Research

News

Harvard Innovation Labs Announces 25 President’s Innovation Challenge Finalists

News

Graduate Student Council To Vote on Meeting Attendance Policy

News

Pop Hits and Politics: At Yardfest, Students Dance to Bedingfield and a Student Band Condemns Trump

News

Billionaire Investor Gerald Chan Under Scrutiny for Neglect of Historic Harvard Square Theater

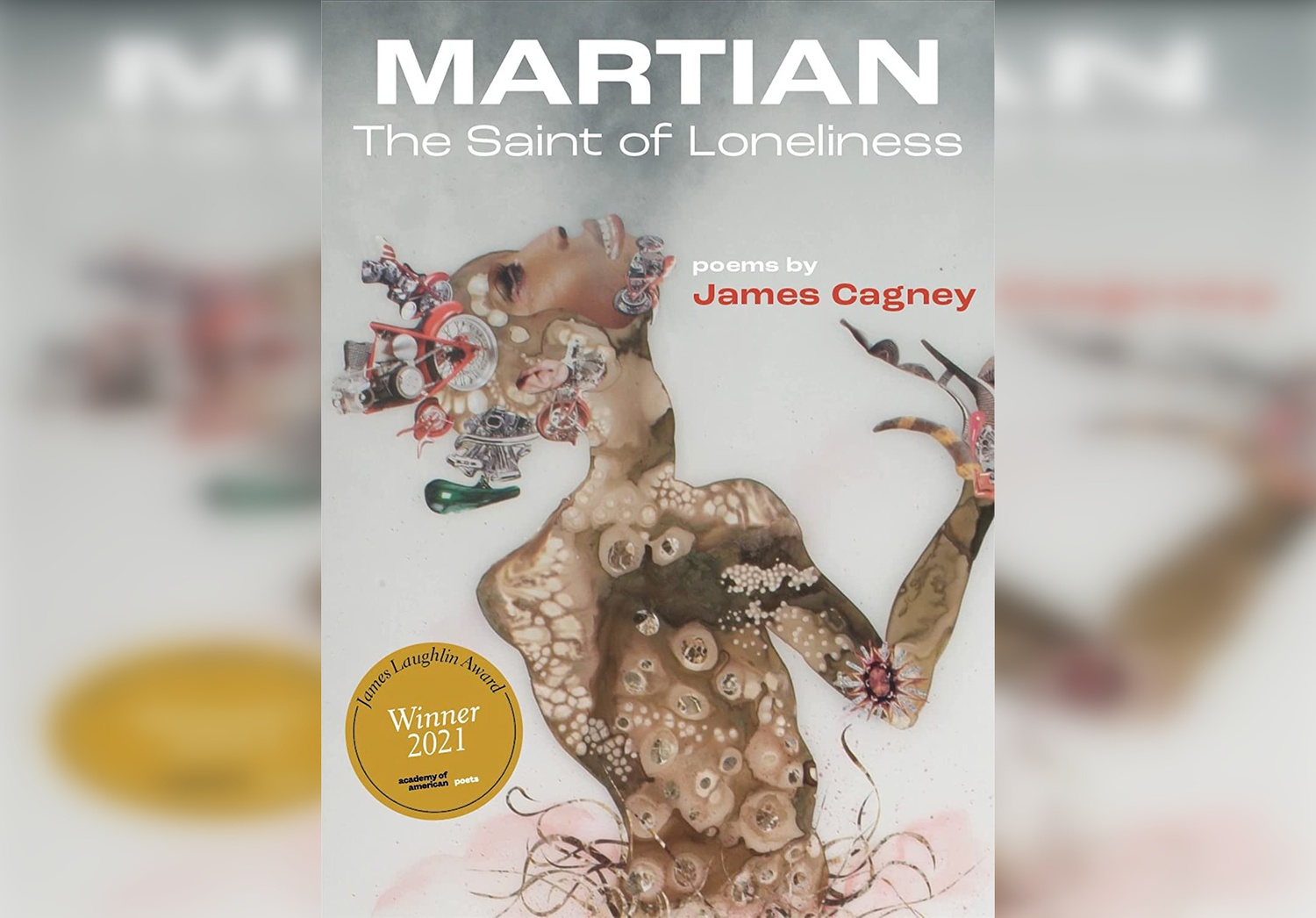

‘Martian: The Saint of Loneliness’ Review: A Break from Convention Done Right

4 Stars

“Martian: The Saint of Loneliness” is a poetry collection brimming with confidence, voice, and presence; it firmly plants its feet, unafraid to be seen or heard, for better or for worse. It is through this shamelessness that award-winning author and poet James Cagney delivers his art, an exhibition of autobiographical vignettes, artistic musings, historical exposés, and bold calls to action that confront the reader with unavoidable introspection. Expert wordplay, constrained breaks in convention, and varied form allow Cagney to explore themes of loneliness and isolation, the legacy of slavery and colonization, and love and passion with a deftness of pen that is by no means light — the collection remains a heavy read from cover to cover.

The star of this work, by far, is the visual artistry of Cagney’s poetry. Honoring his promise to “paint with words,” each poem is designed to be more than just words on the page. Artistic embellishments and unconventional punctuation give Cagney’s poetry a visual flair; akin to a physical artwork, his poems are curated displays rather than rhythmic creations. Spaces of varying length replace commas, and even periods, in poems like “Her Majesty Queen Sophie,” favoring visual artistry over traditional rhythmic form, and creating greater nuance. Not all pauses are equal, but how does the reader make that distinction? The difference between four spaces and seven conveys in precise detail the intended breath.

At the same time, abstract imagery dots the pages of this collection, such as the bullet holes in “Bullet Gumbo,” which often take the place of traditional punctuation — notably bullet points — and underscore the inherent visual nature of this work. Cagney’s protest pieces read like modern art on a gallery wall, while narrative excerpts from his childhood are pastoral landscapes of a human life. This is by no means a criticism of his poems on adolescence — the words are never stagnant, just still. Given that many of these poems originated from a literary interpretation of visual art, including “Phantom Pain” and “Love is Easier the Headless Way,” it should come as no surprise that Cagney’s poetic form frequently reflects his aesthetic inspirations.

Visual art is not the only place from which Cagney derives his muse. Part of the brilliance of this collection stems from a rearrangement of and creative borrowing from others’ writing. “Boys and Stranger” was conceived from Cagney’s “much too personal an essay to publicly share,” “Found in America: Bad Apples” is an arrangement of select words and phrases from other texts, otherwise known as a found poem, and “Between a Rock Wall and an Immigrant” draws from both a poem by Allen Ginsberg and a song by Eddie Jefferson. Art births new art, and this life cycle of creative thought is precisely what makes this poetry not only relatable, but familiar.

This collection benefits from structural as well as aesthetic variety. It strikingly pushes boundaries of poetic form not by writing without form, but rather by creating new structure, and riffing on existing poetic paradigms. “If You See Something,” though it may seem randomly arranged, is actually highly structured; the structure is just of Cagney’s own invention, for which he generously provides instructions in the “notes & acknowledgements” section of the book: “Write a stanza of 4-5 lines, then blow up and reconstruct that stanza four more times, pushing and varying word use as needed.” This procedurally unstructured form provides the collection with another source of uniqueness and variety, making it stand out in a vast sea of modern poetry.

Not every stand-out, however, is for the better. Sometimes the poetry is dense: a wall of text that requires word-by-word dissection. While artful in its own right — sometimes consuming art requires work — this complexity takes away from the reader’s ability to see the big picture in select poems, like “Her Majesty Queen Sophie.” Instead, the reader must toil over the author’s craft. In other cases, however, this collection infantilizes its reader, with a reading guide at the end of the book complete with analysis questions and writing prompts reminiscent of a grade-school classroom. Sufficient background on the poetry is provided in the notes at the end of the book: A reading guide cannot help but read as excessive, unnecessary, and a dampener to the authentic artistic experience.

Still, this poetry collection leaves no deficit of fantastic craft. Once the reader is able to wade through the ocean of praise and forewords that shield the true beginning of this book, what awaits on the other side is well worth it. With a brazen, full-frontal attack of delicate and timely themes, what other collection has the audacity to ask “Could murder be a form of art?” Mold-breaking poetic and visual structure underscores an impressive dissection of what it means to make art in America; the book itself provides a brilliant example, giving the reader an insight into the author’s personal life, all the while framing an insightful callout of America and all who are complicit in its systems of oppression.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

Where you should have gotten your protein since 1998.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

HUSL seeks to create and empower a community of students who are seeking pathways into the Sports Business Industry.