News

News Flash: Memory Shop and Anime Zakka to Open in Harvard Square

News

Harvard Researchers Develop AI-Driven Framework To Study Social Interactions, A Step Forward for Autism Research

News

Harvard Innovation Labs Announces 25 President’s Innovation Challenge Finalists

News

Graduate Student Council To Vote on Meeting Attendance Policy

News

Pop Hits and Politics: At Yardfest, Students Dance to Bedingfield and a Student Band Condemns Trump

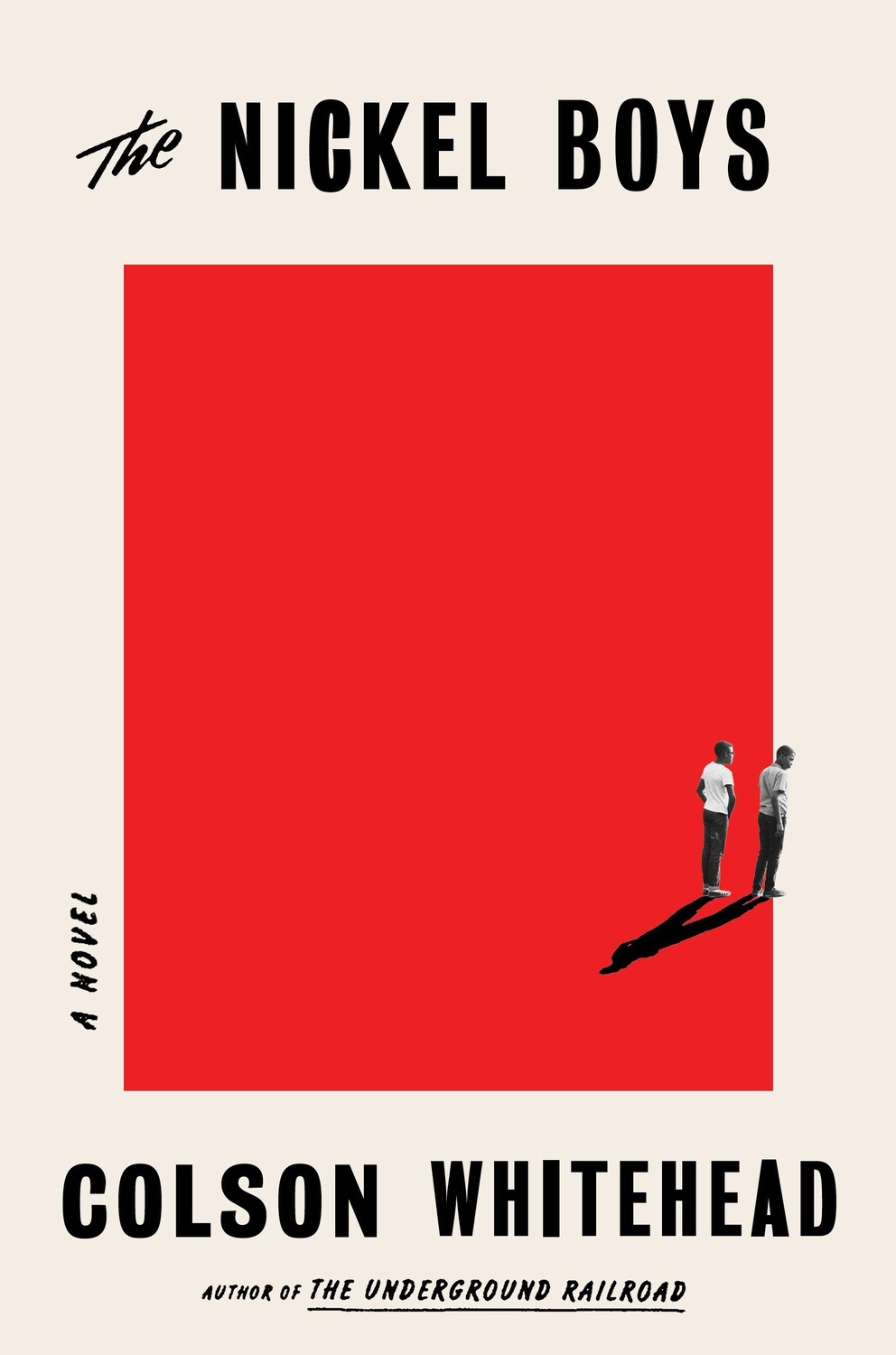

‘The Nickel Boys’ is Both a Shattering and Deeply Necessary Read

4 Stars

Colson Whitehead did not intend to write a heavy, difficult-to-read book, but that’s exactly what “The Nickel Boys” became. Not that there’s anything wrong with that: The novel is a superb read that repeatedly shocks the reader even though it shouldn’t given America’s history of racial violence that continues into the present day. Whitehead writes as any good author should: He envelops the reader into the world of his characters until one reaches a state of familiarity, only to jolt him or her with phrases, sentences, and paragraphs that perfectly express Whitehead’s sentiment of choice, be it shock, fear, injustice, or passion.

“The Nickel Boys” starts out hopeful in a way that signals that things will go wrong very quickly. Elwood is a teenager awakened to the Civil Rights movement by Dr. Martin Luther King, and is described in a way that intensifies his naïveté. On his first day attending college classes as a high school student, he accepts a ride in a car that — unbeknownst to him — is stolen. He is complicit simply by being in the car and is soon sent to Nickel, a facility described to visiting inspectors as a reform school, but which is really the site of unfathomable abuses made all the worse by the racism of Jim Crow era.

Though Nickel is fictional, it is modeled on a school that existed in Florida from 1900 to 2011, around which Florida officials found bodies and unmarked graves. Many of the remains are from black boys, yet few of the bodies have been identified. The state has not yet issued a public apology, in a move that should surprise no one, but dismay everyone.

Turner, one of the only friends (of sorts) that Elwood makes in Nickel, is his polar opposite: cynical, disbelieving of the system, and convinced the only way to get out of Nickel is to bide one’s time and protect oneself at the expense of all else. This bond proves to be a lasting one — and one that keeps both boys sane — as they watch students disappear.

It isn’t often that novels portray sound as effectively as Whitehead does. Yet when he conveys the sound of the fan in the room where beatings take place, he does so with clarity and precision — it permeates the entire campus grounds, and while Elwood can initially take comfort in not knowing why Nickel officials deploy it in the first place, this innocence doesn’t last long. The fan can be heard all over, but in a twist of cruelty, when boys about to be punished stand right next to it, they can hear everything the officials say.

Sound recurs repeatedly throughout, especially the forced silence of the boys who would do anything to get out but find their humanity dulled and destroyed. The narrator, writing from the present day, says as much in a manner that is too bitter to be ironic: “Most of those who know the story of the rings in the trees are dead by now. The iron is still there. Rusty. Deep in the heartwood. Testifying to anyone who cares to listen.”

The end of the novel — which will not be revealed here — is itself a testament to and lament of the dehumanization and deeply entrenched racism which Whitehead chronicles on every page. Naïveté and blind hope cannot protect in the face of hatred: manufactured determination and self-inflicted desensitization perhaps have a better chance. Whitehead points out, however, that this change in boys so young is one of the biggest crimes of all, and is a lesson that follows the men in the story even once they have managed to leave or escape.

“The Nickel Boys” may be fiction, but a similar school was once real, and de facto open in the twenty-first. Elwood’s story points that out to an audience that otherwise, tragically, would not have known, and demands that we confront the legacy of pain that would have otherwise been forgotten.

—Staff writer Cassandra Luca can be reached at cassandra.luca@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

Where you should have gotten your protein since 1998.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

HUSL seeks to create and empower a community of students who are seeking pathways into the Sports Business Industry.