News

When Professors Speak Out, Some Students Stay Quiet. Can Harvard Keep Everyone Talking?

News

Allston Residents, Elected Officials Ask for More Benefits from Harvard’s 10-Year Plan

News

Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin Warns of Federal Data Misuse at IOP Forum

News

Woman Rescued from Freezing Charles River, Transported to Hospital with Serious Injuries

News

Harvard Researchers Develop New Technology to Map Neural Connections

Reconnecting with the Golden Generation: Harvard Basketball in the 1940's

In the early afternoon of Saturday, Feb. 9 — as I was just roused from a late-night slumber, still processing the thrilling triple-overtime game at Lavietes Pavilion the night before — I received a fascinating email in my inbox from a man named Vince Lackner.

Somewhat perplexed by the generic “Harvard Basketball” email title, I quickly scrolled down to the signature. Here, it read, “Vince Lackner ‘72, Harvard Basketball 1970-71”. Intriguing, I thought.

By the time I finished reading the full note, it had dawned on me that I had stumbled into an exciting opportunity— one that would allow me to dive deep into the legacy of a basketball program whose sole NCAA appearance before the arrival of Tommy Amaker came in 1946.

So onwards to Henrietta’s Table in The Charles Hotel I went, as per my invitation. Here, inside a semi-bustling eatery hours past its signature brunch time, I quickly located my party at the front bar area. Already situated and chatting casually were a few individuals: Susan Clark, Brigid Decsi and her son Brian, an older gentlemen named Cliff Crosby, and the man who put this reunion together, Vince Lackner himself.

These names may sound unfamiliar, unless one is a true historian or aficionado of Harvard Basketball. But the common bond that ties these folks together, as well as one more individual I would later speak to over phone named Don Swegan, is one that stretches back to that decade that played host to World War II. As Tom Brokaw would say, this group belonged to the tail end of the Greatest Generation.

But first, let’s go back to that table again. On my left stood Brigid Decsi, whose father Lou had co-captained that historic 1946 Ivy championship team. On my right stood Susan Clark, whose father Jack would later serve as captain of the team the following season. Both Jack Clark and Lou Decsi had recently past away in the last two years, leaving the aforementioned Swegan as the only living member of the 1946 championship team.

And Cliff Crosby? The 90-year old man who would later drive back to his home in New Hampshire was a graduate of Harvard College in 1950, who also earned letters for the Crimson in basketball (as well as baseball/football) in the late 1940s.

Quite a remarkable ensemble, to say the least.

Lou Decsi

Like many of his teammates on that 1946 championship team, Decsi did not arrive in Cambridge his freshman year. Instead, the Akron, Ohio native originally enrolled in Bucknell University through the Navy V-12 officer’s training program. The six-foot-three Decsi captained the basketball team while with the Bisons, and when the war ended in 1945, the V-12 students were re-distributed across ROTC institutions.

One such university happened to be Harvard, and amazingly five of Decsi’s new “V-12” teammates also captained their previous school teams — among this list included ex-Bowling Green skipper and future Celtic Wyndol Gray, Millersburg ex-captain Saul Maraiaschin (another Celtic), and Swegan who led the Baldwin-Wallace side.

Decsi stayed at Harvard for only that one championship season, returning back to Bucknell to conclude his collegiate career. He was one of the starters on that season’s team, playing mostly at center.

“Despite his height, Desci has looked fast and tricky under the boards in pre-season practice,” a Crimson article from Dec. 7, 1945 read.

Following graduation, Decsi embarked on a brief semi-pro career including spending two years with the Celtics’ B team, the Hartford Hurricanes.

“He had some photographs but really what it did for him was it shaped his life,” according to Brigid Decsi, Lou’s daughter. “Because he went from Harvard, then he played semi-pro ball, and then he went on and tried out for the Celtics. He said to me that he never had any regrets because he tried.”

As to Lou’s time in the military service, the trained dirigibles mechanic embraced a nomadic life of sorts, due to his basketball prowess.

“He kept getting moved to different bases because he could play basketball,” Brigid Decsi said. “...Each of the bases had teams and they would compete against each other. If the head of each base wanted their team to win, they would move people, they would try and load their team with the best players so that kept him [in service].”

Following his basketball-playing days, Decsi settled in Connecticut and would later manage the payroll department of the Hartford Insurance Group. Today, Brigid and their extended families continued to call that area their adopted home.

Jack Clark ‘47

Unlike the bounty of transfers on that 1945-1946 squad, Clark was the established veteran on that championship team as their returning captain. But like many on the team, Clark came from humble beginnings as an native of a small town in upstate New York.

The six-foot-two forward was the main scoring target before the arrival of the transfers in ‘45-’46, which relegated him to a role coming off the bench. Still, the Eliot House native maintained a passion, diligence, and love for the sport and of New England that lasted an entire lifetime. Susan, his daughter, recounted how staying active was critical to Jack even in his nineties.

“It was just sort of part of my dad actually, now that I think about it, he would play with much younger guys after work,” Susan Clark recounted. “There was something about [basketball] he just loved."

"He stayed very active into his 90’s. It was part of his life and discipline," added Susan Clark.

Compounded to Jack’s fervor for basketball was an equal appreciation for the university he called home.

“Whatever happened [at Harvard] held a place so ingrained in his feeling for that the college and the people and the sports, he just loved to go back,” Susan Clark said. “And I always went to commencement with him. Every year, we would go and...he didn't talk about experiences that much or particular things other than...just the love of it....And we went into Cambridge. And we walked through the Harvard Yard, and it just couldn't quite get enough of it.”

Up to his later years, Clark maintained an email chain with Coach Tommy Amaker, continuously exchanging thoughts about the team and staying involved with the happenings in the program.

Don Swegan

Unable to be physically present at this reunion, the 94-year old man currently resides in a retirement community near his lifelong home in Youngstown, Ohio. Upon picking up the phone, however, it was obvious that Swegan continued to have an undeniable love for this meaningful game from his younger years.

Swegan’s claim to fame, outside of the fact that he scored the final basket in the NIT Tournament against top-ranked Ohio State to throw off the point spread (“everybody in the crowd went wild!”)?

Remarkably, Swegan had sat only a few seats away from The Great Bambino while waiting for Harvard’s later-afternoon matchup against the Buckeyes.

“We played the NIT and Kentucky played Rhode Island,” Swegan said. “And I stood in the last row of Madison Square Garden, next to Babe Ruth, and sat there the whole game watching the Rhode Island-Kentucky game.”

Due to earning the Ivy League championship, the Crimson had earned just one of eight spots to the national tournament held in the ‘World’s Most Famous Arena’ in New York City. This was an eye-opening experience for many of the members of the team who had spent most of their lives in small-town America.

Swegan also noted how different the rules of the game and style of play were back then, commentating on how he was able to play both basketball, baseball, and football while at Harvard. In fact, Swegan was the captain of the baseball team and represented Harvard at the only East-West College baseball game at Fenway Park.

“The coach could not meet with the players at a timeout,” Swegan said. “So when timeout was called you had to stand there under the basket. But the coach was not allowed to interact with you at that time.”

When you went to screen for a man so somebody could get a cut or a shot you had to be three feet away from the guy that you were screening...if you got right up to a guy they would call it a pick.”

You could not invade the basket cylinder, you could not catch your hand in there. So there was no dunking or jamming of the ball.”

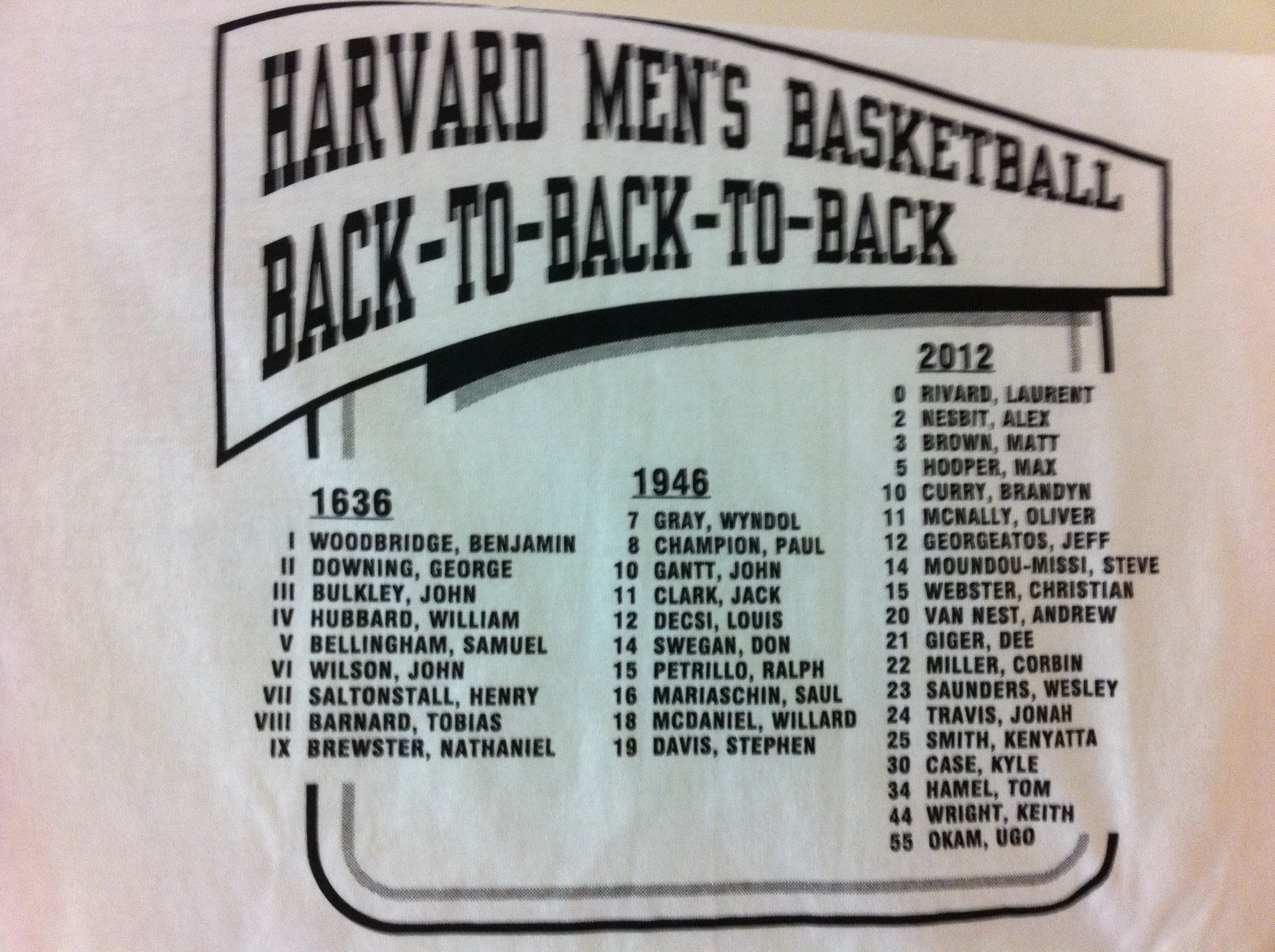

Swegan stayed at Harvard for only one season, but he gained some notoriety after being invited by the Friends of Harvard Basketball to attend the Crimson’s first NCAA Tournament game since his own 1946 contest at MSG. Harvard earned that long-awaited berth in 2012, and Swegan was the sole representative of that class to attend the game in Albuquerque.

“Maybe they were surprised I lived that long,” said Swegan on interacting with the 2012 team. “I don't know. Anyway, we had some good action interaction with the players and with the parents and so on. And I thoroughly enjoyed it.”

At the banquet later that month, Swegan reunited with his old teammate Jack Clark, their first meeting in 66 years. At his retirement home, that reunion photo still hangs high as a reminder of their collegiate friendship.

“[Jack Clark] is a wonderful guy, a tremendous man, and we have that on my wall here at home,” Swegan said. “I've got some pictures with him when I was out there in Cambridge for the banquet.”

Cliff Crosby ‘50

Similar to Swegan, Crosby was a standout multi-sport athlete at Harvard who outrightly declared baseball as his strongest sport. A dominant reliever who according to a 1950 Crimson article solved “the one Crimson weakness, and the one which was responsible for the great number of its defeats, [which was] the lack of adequate mound strength for relief purposes,” Crosby also excelled as a catcher.

Crosby enrolled in Cambridge the fall of 1946, when many of the ROTC transfers had already left campus. But the New Hampshire native still vividly recalled the post-war excitement that had dispersed throughout the university.

“All the people who had served in the war were coming back, so there were young people just out of high school and veterans,” Crosby said. “But they all wanted to do sports. They still couldn’t let go of all the fighting and the fun they got out of it, which was teamwork and maturity of the group. It was wonderful to watch.”

On the basketball court, Crosby had some compelling stories. First, as one of the strongest defenders on the team, he would often be pitted with the most talented opponents — among this list included none other than Holy Cross’ Bob Cousy.

As members of the same graduating class, Crosby was pitted against Cousy in all four years, losing to the Crusaders in each of its attempts. The ex-Harvard guard commented on Cousy’s shiftiness and aggressiveness as distinguishing qualities in his play.

Another neat fact? Not only did Harvard send a few of their best players to the Celtics, the team often practiced against their professional counterparts.

“Basketball wasn’t a big thing and the Celtics were just starting,” Crosby said. “We actually scrimmaged them. There were two players I remember, one was Eddie Ehlers from Purdue. He had a crossover dribble. The other was Ed Sadowski. He had a particular motion when he got down on the post, he would hit you in the chest. When he did it to college boys you would feel it.”

Finally, the college teams around Boston in the forties would frequently play games at the Boston Garden back then. Alongside the Holy Cross rivalry, the Crimson also battled Boston College and Princeton among other squads in the hallowed, 13,000-plus seat grounds. Certainly an experience worth cherishing and retelling for future generations.

Vince Lackner ‘72

A native of Pittsburgh, PA., this lawyer and estate administration software developer was the glue to this entire operation, connecting several long-lost members of that 1946 team and organizing this reunion before the Cornell game on Feb. 9.

A member of the team in 1970-71 (a “pine brother”, as he describes it), Lackner has since become an ardent supporter of the program and de-facto historian of sorts. Specifically integrating his interest and background in data/analytics, Lackner helped coordinate the trip to Albuquerque where Swegan was able to attend the 2012 tournament game while taking an active role in connecting the Harvard basketball community.

“I want to do more of that, because I can do it,” Lackner said. “I’ve got the data, skillset, experience and motivation. I can visualize and geo-code to help people know where the others are, and help them connect. Because it just means a lot...I love the term called friend-raising.”

Among one of Lackner’s projects is compiling a database of all student-athletes who ever played basketball in the Ivy League, something that Ivy League Executive Director Robin Harris expressed interest in at the Harvard-Stanford game in Shanghai in November 2016. The database, updated through 2017, currently lists 4,541 men (starting in 1900) and 1,551 women (starting in 1921). Lackner looks forward to taking the next step with this information.

“There’s so many stories, so many interesting things that so many people have done in their lives,” Lackner added. “And there’s a lot of joy that they experience to share that with others.”

The history and people behind Harvard Basketball continues and many of these pieces are only beginning to come into picture, both past and present.

— Staff writer Henry Zhu can be reached at henry.zhu@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @Zhuhen88.

Correction: Mar. 1, 2019

The original version of the article was incorrectly published, and the modified version has since been updated.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.