News

When Professors Speak Out, Some Students Stay Quiet. Can Harvard Keep Everyone Talking?

News

Allston Residents, Elected Officials Ask for More Benefits from Harvard’s 10-Year Plan

News

Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin Warns of Federal Data Misuse at IOP Forum

News

Woman Rescued from Freezing Charles River, Transported to Hospital with Serious Injuries

News

Harvard Researchers Develop New Technology to Map Neural Connections

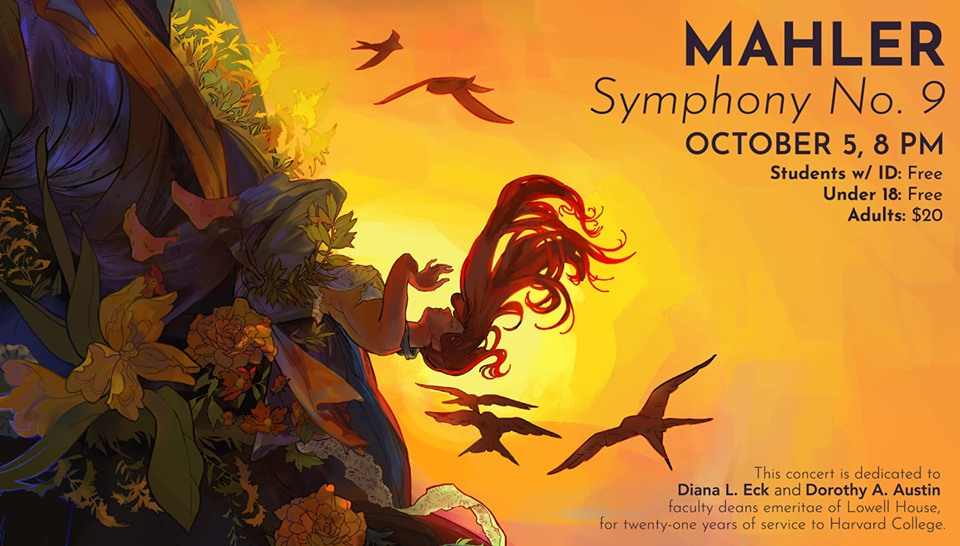

Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra Recreates the Bittersweet Romance of Mahler’s Ninth

Can you hear your heart right now? We often forget that it is there, beating restlessly and constantly, that we will stop existing when it ceases to make a sound. Gustav Mahler probably thought about this a lot, especially after being diagnosed with a heart disease at the age of 47. His abnormal heartbeat became a constant reminder of both life and death — the sound of what was keeping him alive and what would one day ultimately end his life. On Oct. 5, the Harvard Radcliffe Orchestra, conducted by Maestro Federico Cortese, played Mahler’s Ninth Symphony in Sanders Theatre. They dedicated the concert to the previous faculty deans of Lowell House, Dorothy A. Austin and Diana L. Eck, for their 21 years of service to Harvard College. Mahler’s Ninth starts with simple scales given by a single cello, then a horn, and then a harp. The notes call back again and again to Mahler’s conspicuous mortality.

“The first thing we hear in this movement is actually a premonition of death in the form of an irregular rhythm,” the late composer Leonard Bernstein said of the piece, “which I have always been convinced is a documentation by Mahler of his own irregular heartbeat.” According to Bernstein, each of the movements in Mahler’s Ninth Symphony is one of the composer’s final farewells to life, the first movement bidding farewell to tenderness. Appreciating this in concert did not require a trained ear. Just by listening to the first five minutes of the orchestra skillfully play Mahler’s dynamic melodies brought to life the nostalgia written into his scores. Each phrase of the first movement sounded like advice from an old man who has thought long and hard about life in the light of his inexorable death. A romantic theme creeped beneath the movement, peeking through the dramatic sways of the string and the striking eruptions of the brass.

This theme of romantic melodies is akin to that of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1, but is fundamentally different in nature. Mahler’s might seem extremely romantic at first, but it is far richer in meaning. The Harvard Radcliffe Orchestra plays this sublime theme in masterful contrast to the most dramatic and loudest phrases you will hear an orchestra play, making the romance of the melody even more beautiful. It is impossible not to feel touched by memories of the dearest moments of life, but it is equally impossible not to feel frustrated when the orchestra’s cellists, like Mahler’s heart, flutter with the reminder that we will soon enough lose it all. This frustration does not make life any less beautiful, and the Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra expertly captures the fight and resolution between the beauty of memory and the pain of distance that made Mahler’s reflection of life so appealing.

This is the essence of Mahler’s Ninth. He is deeply in love with his life, but he is soon going to leave this world. The orchestra shifted from minor to major with outstanding ease. It turned to intense dramatism in an instant. It became the sweetest of melodies. It turned to almost complete silence. Love and anger. Happiness and frustration. Nostalgia. Maestro Federico Cortese was evidently taken by the hurricane of the music. His breadth audibly escaped as he conducted the most aggressive movements of the symphony. He could be seen trying to rest as much as possible in the few seconds between movements. Indeed, every single moment of the ninety-minute symphony resonated with deeply personal force.

The symphony closed in an unexpected way. Long, quiet phrases dominate the fourth and final movements. Mahler’s heart fades out. With its stretched silences, it only felt natural to let eyelids fall as the orchestra heralded the end of life. The minor phrases of the first two violins were the tender reminder of how many things we all have lost and will lose, and the joy of having had the privilege of being happy at least once. By the end, the orchestra turned to a stoic meditation by the faintest, seemingly infinite, notes of the strings. The Harvard Radcliffe Orchestra’s delivery of Mahler’s Ninth left the audience stunned. The silence hung in the air for a moment before shattering into applause.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.