News

Nearly 200 Harvard Affiliates Rally on Widener Steps To Protest Arrest of Columbia Student

News

CPS Will Increase Staffing At Schools Receiving Kennedy-Longfellow Students

News

‘Feels Like Christmas’: Freshmen Revel in Annual Housing Day Festivities

News

Susan Wolf Delivers 2025 Mala Soloman Kamm Lecture in Ethics

News

Harvard Law School Students Pass Referendum Urging University To Divest From Israel

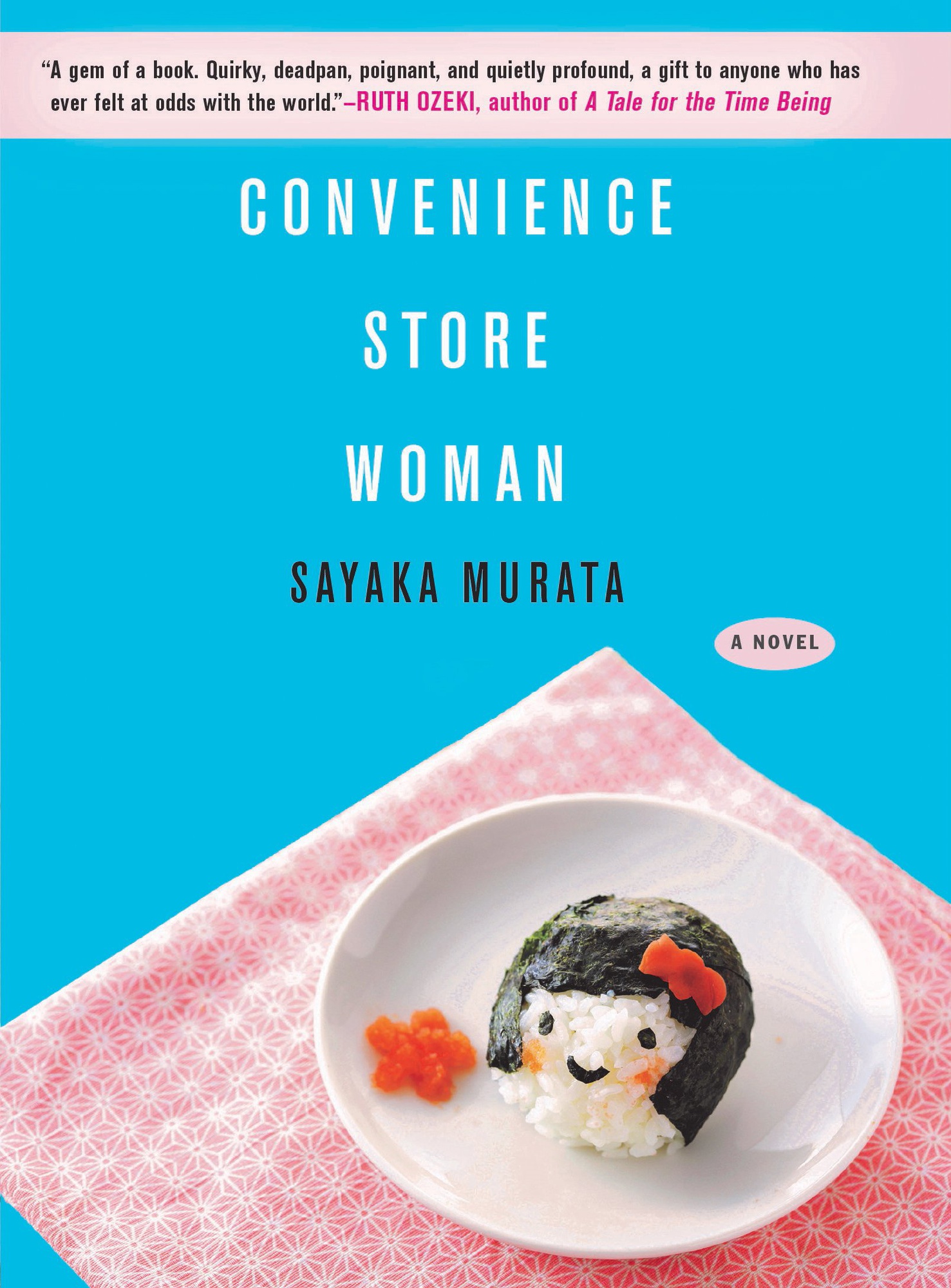

Sayaka Murata’s ‘Convenience Store Woman’ Asks You to Reconsider ‘Normal’

4 Stars

Keiko Furukura says that above all, she is a convenience store worker, even “more than [she is] a person.” And she prefers it that way, even if her family, friends, and coworkers make it their business to think otherwise. Keiko, the heroine of Sayaka Murata’s novel “Convenience Store Woman” (translated from Japanese to English by Ginny Tapley Takemori), is a refreshing narrator with a fascinating voice, always bluntly honest about society’s strange obsession with her single status and growing age, but never bitterly so. Together, Murata and her protagonist lead a novel that is delightfully candid and unexpectedly empowering, a feminist tale that blooms inside the small world of a 24-hour convenience store.

Keiko is considered an outlier of society: She is 36, has never been in a romantic relationship, and is still working the same convenience store job she’s had since she was 18. Though Keiko doesn’t really care about marrying or having children or applying for higher-level work, everyone around Keiko seems bewildered by her satisfaction with stasis. Eventually, Keiko gets tired of her sister and her friends either quietly tiptoeing around the subject or loudly pointing out her abnormalities. So she asks her spitefully cynical and misogynistic coworker—Shiraha—to move in. At first, living in a cramped space with an entirely unpleasant person seems worth it because her friends stop pestering her about her relationship status. “People who are considered normal enjoy putting those who aren’t on trial, you know,” Shiraha points out. But something strange happens: Now, everyone’s obsessed with talking about Keiko and Shiraha, even though the duo are a strictly platonic couple.

Murata is undeniably hilarious. Her humor works subtly, mostly when there are discrepancies between what Keiko and what society thinks is rational. Keiko recalls the time she found a dead bluebird in the park. All the other children started crying, but Keiko wanted to grill and eat it instead. It might seem macabre, but after hearing Keiko’s reasoning, turning the dead burn into yakitori makes so much more sense. “Everyone was crying for the poor dead bird as they went around murdering flowers, plucking their stalks, exclaiming, “What lovely flowers! Little Mr. Budgie will definitely be pleased,” Keiko says of the children’s makeshift funeral. “They looked so bizarre I thought they must all be out of their minds.” The logic that is so reasonable to Keiko (the narrator leading the story) and to the reader isn’t to anyone else. It’s not just funny, but thematically relevant: Murata’s humor redefines what we might consider “normal.”

And it’s clear that Keiko’s devotion to the convenience store isn’t meant to be “normal.” Murata found inspiration for this novel from her own days working part-time at a convenience store and possibly used that experience to immerse the first few pages in the shop’s sounds and motions. For Keiko, the minute actions of the convenience store move as seamlessly as poetry: “From the tinkle of the door chime to the voices of TV celebrities advertising new products over the in-store cable network, to the calls of the store workers, the beeps of the barcode scanner, the rustle of customer picking up items and placing them in baskets, and the clacking of heels walking around the store.” The novel wants you to fall in love with Keiko’s profession as much as she is infatuated with it, and it’s hard not to, considering how brilliantly intricate and inconspicuously vibrant this landscape can be with Murata’s carefully descriptive prose.

So it’s all the more tragic when Keiko is ripped away from this world, forced to hunt for another higher-level job in order to continue living the lie that she and Shiraha are dating. She falls into a depression, unwilling to do much else besides barely exist. “I would carry my genes carefully to my grave, being sure not to rashly leave any behind, and I would dispose of them properly when I died,” she says, after Shiraha’s sister-in-law cruelly says to her that Keiko is too abnormal to even consider having children as a way to fulfill her societal obligations. “I was resolved on this, but at the same time it left me in a bit of a limbo. I understood the end point perfectly, but how was I to spend my time until then?”

But the answer was always there—the very place where Keiko was told she couldn’t stay. On her way to a job interview at Shiraha’s request, Keiko passes a convenience store, and something clicks. She goes inside instead, and immediately starts rearranging the aisles and giving recommendations to the cashier. “I could hear the store’s voice telling me what it wanted, how it wanted to be,” she says. “I understood it perfectly.”

This is Keiko’s very own hero’s journey, a brilliantly crafted one that defies standards for women. “My very cells exist for the convenience store,” Keiko says, and she is happy that way, despite her sister’s demands for marriage, despite Shiraha’s demands for a higher-level job, despite every other person telling her that the very thing that makes her happy is the very thing that makes her abnormal. The most triumphant part of the novel is when Keiko realizes that she simply doesn’t care. “That’s grotesque. You’re not human!” Shiraha condemns Keiko after she chooses the convenience store over him and the possibility of leading a “normal” life. “That’s what I’ve been trying to tell you!” Keiko thinks.

“Convenience Store Woman”’s premise might trick you into thinking that it’ll end up a love story between a man and a woman, given how quickly and easily Shiraha is introduced as a potential solution to all of Keiko’s problems. But with her sharp critiques and subtle humor, Murata makes it clear that this is not the case. The real love story is between Keiko Furukura and her beloved convenience store, as it was in the title all along.

—Staff writer Grace Z. Li can be reached at grace.li@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @gracezhali.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

Most Read

- Harvard Dismisses Leaders of Center for Middle Eastern Studies

- 2 Years After Affirmative Action Ruling, Harvard Admits Class of 2029 Without Releasing Data

- Russian HMS Researcher Detained at Louisiana ICE Facility After Visa Revocation

- Harvard Agrees to a 1-Year $6 Million PILOT Agreement With the City of Cambridge

- More Than 600 Harvard Faculty Urge Governing Boards To Resist Demands From Trump

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

With innovative financial tools combined with financial education, Collegiate empowers students to take control of their finances and build confidence in their money management skills.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

Admit Expert is a premium MBA admissions consulting company, helping candidates secure admission to top B-schools across the globe with significant scholarships.