News

HMS Is Facing a Deficit. Under Trump, Some Fear It May Get Worse.

News

Cambridge Police Respond to Three Armed Robberies Over Holiday Weekend

News

What’s Next for Harvard’s Legacy of Slavery Initiative?

News

MassDOT Adds Unpopular Train Layover to Allston I-90 Project in Sudden Reversal

News

Denied Winter Campus Housing, International Students Scramble to Find Alternative Options

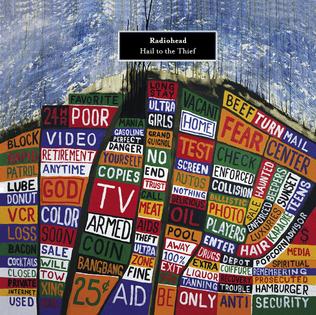

Timely and Foreboding, Radiohead’s ‘Hail to the Thief’ Turns 15

It was 2003, and Radiohead didn’t need another pristine masterpiece. They needed to express outrage, and they outdid themselves in this regard with their messy sixth album “Hail to the Thief,” which celebrated its fifteenth anniversary on June 9th.

The most political Radiohead album ever, “Hail to the Thief” brandishes anger at the unjust wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the disputed election of former president George W. Bush (the “thief” being ironically hailed in the album’s title), the rise of right-wing politics in the United States and the United Kingdom, the complacency of their citizens, and the perils of fame. 15 years and three albums later, “Hail to the Thief” is still Radiohead’s angriest and most unbridled record. Simultaneously a mutter and sing-song, strained and explosive, electronic and a return to a guitar-driven rock core, “Hail to the Thief” embodies the frustration and defeat of a bruised animal throwing itself against the bars of a cage—“hysterical and useless,” to quote the band’s earlier work (“let down”). It is a bleak internalization of current events, with its frankness made apparent by its reluctance to offer encouragement, solutions, or anything remotely anthemic.

Following the supernatural electronica of “Kid A” (2000) and the spooky grooves of “Amnesiac” (2001), Radiohead went down a messier path for “Hail to the Thief” in terms of both sound and process. They recorded one track a day in Los Angeles. The band has stated that several strong moments on the album came from accidents—for example, lead singer Thom Yorke wrote the creepy lyrics for “Go to Sleep” and the opening line of the entire album (“Are you such a dreamer to put the world to rights?”) as placeholders that the band ultimately decided were actually brilliant. In a similar vein, the frantic repetition of the phrase “and the rain drops” in “Sit Down. Stand up” was born from an attempt to save the song during a confusing live performance. Many of the songs spiral into maniacally repeating phrases, such as “I will eat you alive” in “Where I End and You Begin” and “no” duplicated dozens of times in “A Wolf at the Door” and “A Punchup at a Wedding.”

A political message propels this agitation: “Hail to the Thief” brings the distrust of autocratic government that the band hinted at in “Kid A” and “Amnesiac” to the forefront. In its opening track “2+2=5,” “Hail to the Thief” begins with the weary voice of a citizen reciting the incorrect sum. As always, Radiohead incorporates dense layers of cultural allusions, and this lyric is one of several in the album that gives an appropriately unnerving melody to the ideation of a mind-controlling regime as described in George Orwell’s “Nineteen Eighty-Four.” With quivery shrieks, the song builds from its initial expression of conformity to one of resistance that culminates with yelps of “Hail to the thief!” In reference to George W. Bush’s disputed win in the 2000 presidential election, this exclamation’s combination of subservience and ironic defiance sets the tone for the entire album.

In addition to being timely and furious, “Hail to the Thief” is also the most tiring piece of Radiohead’s discography. In sound and lyrics, it is foreboding from start to finish. Frontman Thom Yorke’s vocals drag with appropriate sluggishness over percussion that tends toward persistent teeth-chattering. Its imagery is more brutal than ever, ranging from cannibalism to the bombing of a bunker. Still, in typical Radiohead fashion, depictions of physical violence can often be taken as a metaphor for mental turmoil—for example, the hurricane in “Scatterbrain” feels more cerebral than literal. The images of bloodshed and internal disquiet work together to reinforce the album’s sense of dread.

A common critique is that the album is too long at 56 minutes. Consequently, “Hail to the Thief” has consistently ranked in the bottom half of Radiohead’s nine albums. However, among the repertoire of one of the most critically cherished bands of recent years, this is hardly an indictment. The same qualities that make it seem unwieldy in comparison to many of Radiohead’s other works also make it a moment of catharsis and a suitable response to the turmoil of 2003.

At several unsettling moments, Yorke takes on the voice of the authorities he is criticizing. In “Sit Down. Stand up,” Yorke hypnotically croons, “Walk into the jaws of hell” and “we can wipe you out anytime” as if coercing a body of inhabitants into war. When he takes back the voice of the common people, lyrics like “We tried but there was nothing we could do” from the upbeat bop “Backdrifts” and the refrain of “over my dead body” in the unusually folky “Go to Sleep” portray the people as powerless in the face of violence.

In addition to official states, the public eye is another disabling agent. Over the growling guitar of “Myxomatosis,” Yorke complains that he feels “so tongue tied” in the midst of fame and criticism, and “A Punchup at a Wedding” vents frustration about negative press.

However, one track among all the fidgety paranoia offers a fleeting glimpse of hope. A cross between a soothing piano lullaby and a death march, the third track, “Sail to the Moon,” tells Yorke’s then-infant son Noah, “Maybe you’ll be president / But know right from wrong.” While the rest of the album doubles down on the concept of the varied narrators’ powerlessness, this croon finds hope for reform in the next generation.

“Sail to the Moon” is not the only song that reveals the effects of fatherhood on Yorke. In the stripped-down “I Will,” which emotionally expands on the imagery of “Kid A”’s “Idioteque,” the narrator pledges to protect his children from an event like one he had heard about in the first Gulf War, an attack on a bomb shelter full of women and children. In the pessimistic album closer “A Wolf at the Door,” the narrator sings of a capitalist government’s ability to take away his children.

15 years later, Yorke’s son is nearing adulthood, and Yorke would probably assert that the same global issues he lamented in “Hail to the Thief” are even more in need of fixing today. Yorke has been an outspoken Twitter critic of President Trump, and the concepts of “doublethink,” world leaders threatening violence, and an electoral college “thief” loom large.

At performances of “2+2=5” during their 2016 tour in the United States, Yorke ended the song by shouting “Donald Trump” instead of the usual lyric “maybe not.” This revision catapulted “Hail to the Thief”’s frustration into the present day, and it proved the adaptability of the album’s anger just as much as it pointed out a political backslide.

Though their three albums following “Hail to the Thief” were comparatively introspective and luminous, Radiohead has not avoided seething political commentary. Arguably, the most protest-worthy track published since “Hail to the Thief” has been “Burn the Witch,” a critique of mass hysteria that opens their latest album, “A Moon Shaped Pool” (2016). Six months after its release in May 2016, Yorke tweeted a link to the song in reaction to Trump’s victory.

Perhaps Radiohead will find inspiration from the current political moment in their future works. Still, despite the parallels between the present day and the tumultuous era that kicked off “Hail to the Thief,” nothing close to the 2003 album should be expected: Radiohead’s drive to innovate has consistently allowed them to push boundaries and break expectations, all while articulating the anguish of each moment in time. In all its heaviness and gore, “Hail to the Thief” remains Radiohead’s clearest and most impassioned example of this capability.

—Staff Writer Liana E. Chow can be reached at liana.chow@thecrimson.com.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.