News

News Flash: Memory Shop and Anime Zakka to Open in Harvard Square

News

Harvard Researchers Develop AI-Driven Framework To Study Social Interactions, A Step Forward for Autism Research

News

Harvard Innovation Labs Announces 25 President’s Innovation Challenge Finalists

News

Graduate Student Council To Vote on Meeting Attendance Policy

News

Pop Hits and Politics: At Yardfest, Students Dance to Bedingfield and a Student Band Condemns Trump

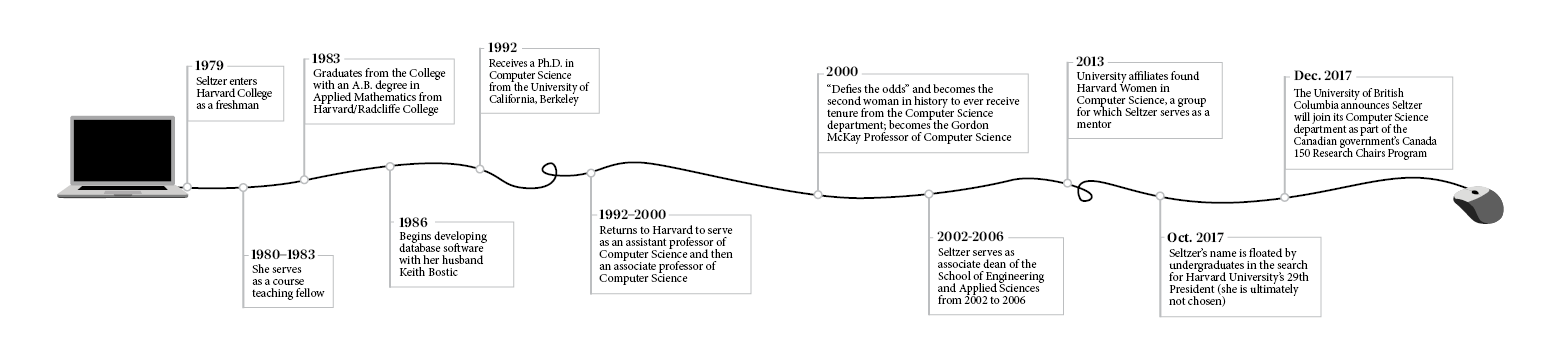

Margo Seltzer, the 'Soul' of SEAS, Leaves Legacy

Margo I. Seltzer ’83 began her nearly three decade career teaching Computer Science at Harvard almost by accident.

As an undergraduate at the College, she knew she wanted to pursue studies in Science, Technology, Engineering, or Mathematics; she had “always been a mathy science person,” she says. But she also wanted to avoid writing a thesis and undergoing a general examination—the latter of which “scared the living daylights” out of her.

So she propped open Harvard’s course handbook and ran through every single “mathy science concentration” which conferred honors without requiring a thesis or general examination. At the time, the College did not offer a concentration in Computer Science; Seltzer settled on the closest thing, Applied Math.

Later, deciding whether to attend graduate school, Seltzer made the final call based on an off-hand comment from an ex-boyfriend who implied she was not serious about the idea. She applied and enrolled in the Computer Science Ph.D. program at the University of California, Berkeley.

“I do not recommend this as a decision-making tactic,” Seltzer says. “But it sort of worked for me.”

More than 30 years later, Seltzer has become a well-known name in Harvard’s Computer Science department and within the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences more broadly.

She now plans to leave Cambridge; Seltzer announced in Dec. 2017 that she is departing Harvard for Vancouver, where she will take part in Canada 150, a multi-million dollar federal research program at the University of British Columbia.

As Seltzer prepares to bid the University goodbye, current and former colleagues and students say she will be sorely missed: as an academic and teacher, as an icon and advocate for women, and as a mentor and guide.

Across the arc of her career, Seltzer balanced teaching commitments with founding and running a startup, broke gender barriers while pushing for gender parity, and helped shape the rise of Harvard Computer Science. She was the second woman to ever receive tenure in the CS department.

“She is the essence of SEAS, she is the essence of Computer Science,” says Evelyn Hu, a professor of applied physics and electrical engineering. “It’s like losing something essential, like your liver, your heart, and to some extent, it is losing some of our soul.”

Reflecting back on her accidental start, Seltzer gives a less vaunted assessment.

“It seems to have worked out okay,” she says.

‘A LITTLE CRAZY, A LOT CRAZY’

Seltzer began stuffing and straining her schedule to its limits at an early age.

As an undergraduate at the College, Seltzer took on various assistant teaching positions and also worked two different part-time jobs: one as a computer instructor and one as an employee at a company in Lexington that developed software to manage stock portfolios.

Carol E. Sandstrom ’83, who shared a bathroom with Seltzer in their freshman dormitory, Matthews Hall, remembers Seltzer once telling her over dinner that she had bought a car. Sandstrom, taken aback, asked why. Seltzer explained her old car had broken down and that she needed a replacement so she could keep “commuting to work.”

“I realized that she was basically holding down a full-time job at the same time that she was executing a demanding Harvard schedule—I don’t know, maybe she was taking five classes,” Sandstrom says. “That just struck me as kind of unusual, that she went out and bought a Toyota Corolla… I didn’t know that you could do that when you were 19 years old.”

But Seltzer was determined not to let her work commitments interfere with her studies or her teaching. She balanced all three competing claims on her time—a pattern she would continue throughout her time at Harvard, at one point working her way through the ranks of Harvard’s faculty while also launching and managing a start-up.

After a brief stint at UC Berkeley for graduate school, Seltzer returned to Harvard and earned a position as an assistant professor of Computer Science in 1992. Shortly before she started at Harvard, she published a software product she had begun developing while at Berkeley.

She created the software—a database program meant to make it easier to find and store information—in concert with her husband, whom she met at Berkeley. After publication, several companies expressed interest in the software, prompting the couple to work furiously to create an “industrial grade version” of the program.

For the next several years, Seltzer lived a double life: She spent her days fulfilling her duties as an associate professor and her nights building software with her husband.

“There were the first 40 hours where we did our day jobs and then there were the second 40 hours where we were building the software. So that was a little crazy, a lot crazy,” Seltzer says.

The end result was “Berkeley DB,” a high-performance software used to generate databases.

Seltzer and her husband then founded a start-up, dubbed “Sleepycat Software,” to maintain and sell Berkeley DB. Sleepycat Software remained profitable throughout its almost decade of existence.

“Timing is everything, and we really hit the first dotcom boom as the market was rising,” Seltzer says.

The duo ran Sleepycat Software for nine years before selling it to Oracle, which as of 2015 was the second-largest software maker after Microsoft. Though her husband left Oracle after a few years, Seltzer continues to work for the company.

Seltzer says her continued involvement with industry work ensures she remains “grounded in research that actually matters.”

“It’s sometimes easy to get interested in problems that I’ve described as ‘Well, if things could fly, dot, dot, dot,’” Seltzer said. “Connections with industry help make sure that I’m solving real problems and not making them up.”

Despite her industry ties, Seltzer did not neglect her teaching; four years after starting as an associate professor, she won the prestigious Phi Beta Kappa teaching award, given to three members of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences each year. Three years after that, she garnered the Roslyn Abrahamson award for excellence in undergraduate teaching. In 2000, she became a tenured professor.

Shortly after reaching that milestone, Seltzer was appointed associate dean of SEAS in 2002. She held the position until 2006. In the course of her career, she estimates she has taught roughly 50 iterations of nine different classes and more than 2,500 students.

Nathan Goodman, a former Harvard Computer Science professor for whom Seltzer once served as a teaching fellow, remembers Seltzer in the early years. He says she manages her demanding schedule—has always managed her demanding schedule—by working “amazingly hard” and being “very diligent.”

He recalled a time when—while working as his teaching fellow—she single-handedly filled out the class grading sheet when he almost forgot to submit enrollees’ grades to the registrar.

“She has a work ethic beyond belief,” Goodman says. “I’ve never felt I could keep up with her at anything.”

A CAREER OF FIRSTS

Beyond professional accomplishments and teaching honors, Seltzer’s time at Harvard has been dotted with gender-related milestones.

While at the College, she was the first woman to serve as conductor of the Harvard University band. She was the second woman in Harvard history to earn tenure in the Computer Science department and she was the first member of the SEAS faculty to ever give birth while holding a teaching position. When she steps down, she will be the first woman to ever retire from SEAS.

Colleagues and students say Seltzer set an example that has inspired women studying STEM across the years at Harvard.

“She faced—women in that generation, and sadly it’s still the case, face discrimination, prejudice, either overt or subtle,” Goodman says. “She never talked about it. She simply overcame it.”

“Hopefully with people like Margo as examples, it becomes easier for each class of women,” he says.

Asked about the Harvard accomplishments she treasures most, Seltzer in part points to the moment she had to tell then-dean of SEAS, Paul Martin, she was pregnant.

Martin had “never had this happen before,” Seltzer remembers. He asked her what she planned to do. Seltzer told him she would co-teach in the fall with another professor, have the baby in December, and come back to teach in the spring, bringing her child with her.

“And he was like, ‘Okay.’ And that was it,” she remembers. “So that was remarkable and astonishing and wonderful.”

Throughout the early years of motherhood, Seltzer—who later had a second child, a daughter—stuck to the policy of keeping her children with her. She remembers bringing her kids to work and on work-related trips, a decision she calls somewhat “crazy” in retrospect.

“Traveling with two kids under the age of five is really insane and yet some of the strongest memories I have and some of the memories that they have are those trips that we did together,” Seltzer says.

Others in SEAS say Seltzer’s unapologetic insistence on being both a mother and a professor reshaped Harvard norms for the better. Keith A. Smith, one of Seltzer’s former graduate students, says Seltzer made her kids’ presence in the office seem “perfectly natural.”

“My daughter was born eight months after Tynan [Seltzer’s son]. And it seemed perfectly natural that she would come to the office if that’s what we needed because Margo had set that example,” Smith says.

Smith emphasizes that Seltzer’s choice to bring her children to work did not “make her less productive or less accomplished.”

He points to one episode—near the time Seltzer was expecting her second child—when she and Smith embarked on a research project with peers at Carnegie Mellon University. The CMU collaborators included a male professors whose wife was also expecting a child.

Days after giving birth, Seltzer started work again, making comments on the paper the group was co-authoring, Smith remembers.

The CMU professor, by contrast, “disappeared” after his wife gave birth, Smith says.

“She’s sort of superhuman in that way,” Smith says. “The professor at CMU has told this story for years because he was so flabbergasted, because he was so wiped out with having a kid and his wife, and supporting his wife and everything, that he couldn’t imagine doing his work.”

In addition to setting firsts herself, Seltzer advocated for other women in the field and worked to improve the confidence of and retention rates for female students in Computer Science.

Seltzer serves as a faculty advisor for the group Harvard Women in Computer Science, a club that provides mentorship and education to women at Harvard and in Boston who want to pursue careers in computer science. Suriya Kandaswamy ’20, formerly one of Seltzer’s advisees, says Seltzer has focused on ensuring women in SEAS “build confidence” in their classes.

Janet Chen ’19, a former co-president of WiCS, said the group at one point sent a survey to female CS students asking them to name their most influential mentors.

“Overwhelmingly, Margo was the first person that people listed—and there are a lot of CS undergrads—but she has made time for everyone and made space for everyone in her life in her very busy days,” Chen says.

‘A SYSTEMS BUILDER’

Fresh out of graduate school, Seltzer was yet again faced with a career-defining decision.

She was staring down a dozen offers to join top-ranked universities. This time around, though, she worked through her options methodically.

Citing her love for the city of Boston, Seltzer says she eventually narrowed her decision to MIT or Harvard. At the time, Harvard’s CS department was “tiny and essentially nowhere to be seen in the rankings,” Seltzer says.

But Seltzer was not daunted. She realized that, by picking the University, she would be able to leave her mark on the fledgling department.

“I’m a systems builder. You can build systems using computers, but you can also build systems using people. And so that was super appealing,” Seltzer says.

With Seltzer’s help—particularly through her efforts to advocate for and mentor junior faculty—the CS department has grown significantly. The department only had seven or eight faculty when she started, according to Seltzer. Today, the department boasts more than 35 professors.

But colleagues say she did more than simply build the numbers—she never shied from turning a critical eye to the department’s inner workings. Colleagues note Seltzer has always been very vocal in expressing her opinions.

“She was very vocal, much more than the rest of us dared to be, so it was really fun to have someone so determined to express our thoughts and our ideas and she was always at the forefront—a real leader,” said Efthimios Kaxiras, who worked as a junior faculty member in the CS department at the same time as Seltzer.

Director of Graduate Academic Programs in SEAS John Girash pointed to Seltzer’s “truth to power” as one of the things he will miss most about her when she leaves. He says he will also miss the way she refused to take “any guff, not taking any of the bureaucratic or administrative cultural cruft without saying why.”

Chen says she thinks Seltzer has never been afraid to say what is on her mind, even when “it’s an unpopular opinion or people don’t want to hear it.”

In one example, Seltzer critiqued the College’s controversial May 2016 decision to sanction members of single-gender social organizations. Seltzer, along with Lewis, Government professor Eric M. Nelson ’99, and Classics professor Richard F. Thomas, penned a Sept. 2016 op-ed in The Crimson arguing against the penalties.

Seltzer says she has always thought one of the most powerful forms of leadership entails “being willing to speak up when things aren’t going the way they should be going.”

As she prepares to leave, Seltzer says she knows Harvard can do a lot to improve. She says she hopes the University will continue to grow its Computer Science department, bring in young faculty, and make strides towards a more “inclusive” campus.

“I will miss my colleagues and my students because that’s what life is all about,” Seltzer says. “I really want to see Computer Science continue to realize all the potential that we’ve built.”

Seltzer will not be around Cambridge to help. But some say her legacy in the CS department will linger nonetheless.

“She’s inspired people to be not just students, researchers, scientists, but to be whole people, while also being students, researchers and scientists,” Girash says. “She’s made the place human.”

—Staff writer Alexandra A. Chaidez can be reached at alexandra.chaidez@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @a_achaidez.

—Staff writer Angela N. Fu can be reached at angela.fu@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @angelanfu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

Where you should have gotten your protein since 1998.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

HUSL seeks to create and empower a community of students who are seeking pathways into the Sports Business Industry.