News

HMS Is Facing a Deficit. Under Trump, Some Fear It May Get Worse.

News

Cambridge Police Respond to Three Armed Robberies Over Holiday Weekend

News

What’s Next for Harvard’s Legacy of Slavery Initiative?

News

MassDOT Adds Unpopular Train Layover to Allston I-90 Project in Sudden Reversal

News

Denied Winter Campus Housing, International Students Scramble to Find Alternative Options

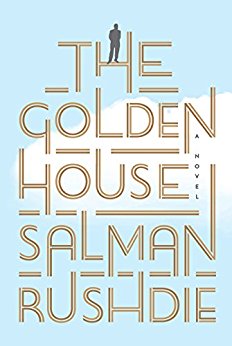

‘The Golden House’: A Meditation on America’s Decline

Salman Rushdie, a writer long celebrated for his masterful command of magical realism, has notably kept his latest novel, “The Golden House,” well within the realm of the real. Rushdie’s style change is due in no small part to the fact that this most recent work deals with the decline of early Obama-era optimism and the rise of bitter sectarianism and vitriol, culminating in the election of President Donald Trump—a series of events so tumultuous that a simple retelling of the past eight years feels surreal enough.

And so Rushdie begins his retelling on the day of Obama’s inauguration, when an unreasonably wealthy and mysterious family moves to Greenwich Village and reinvents itself. As with the rest of his oeuvre, in “The Golden House,” Rushdie relies heavily on myth and allusion to flesh out his characters and create dramatic tension. The patriarch Nero Golden is a man of grandiose stylings, hiding a dark past; his eldest, Petronius, is a garrulous agoraphobe who struggles with his anxieties; the middle son, Apuleius, wrestles with the intersection between art and politics; and the youngest son, Dionysus, faces a bitter and damaging conflict with his own identity.

Rushdie speaks through René, an aspiring filmmaker who views the mystique and spectacle of his newly arrived neighbors as inspiration for his upcoming film. By embedding himself in the lives of the Goldens, René embarks on an eight-year-long journey familiar to many Americans who lived through the Obama years; a journey in which online and real life echo chambers breed sectarian resentment and bigotry; a process where the very idea of identity, whether that be sexual, gender-based, or racial, gets caught in a vicious game of tug-of-war between an increasingly social justice-oriented left and an increasingly reactionary right; a period of time where previously untouchable conceptions like truth become politicized.

This journey, of course, culminates with the election of “the Joker,” a character who surprisingly plays only a minor role. The brilliance of Rushdie is that he portrays Trump as not a disease but as a symptom. Rushdie makes clear that Trump was not a tragedy that befell an undeserving America but in fact a direct reflection of the way Americans interact with themselves and the world. “We are so divided, so hostile to one another, so driven by sanctimony and scorn, so lost in cynicism, that we call our pomposity idealism, so disenchanted with our rulers, so willing to jeer at the institutions of our state, that the very word goodness has been emptied of meaning,” says the narrator.

A bleak resignation, this sentiment is also a call to action, as a way to rid ourselves of not just Trump, but the modes of living which made Trump possible. In the final pages of the book, Rushdie speaks straight to the reader that in the midst of “whatever manufactroversy, whatever horror or stupidity or ugliness or disgrace … our little lives are perhaps as much as we are able to comprehend.” In the face of a frightening new political reality, we must not only confront the regime but begin to confront ourselves.

The failure of the novel ultimately comes from the breadth of content it tries to cover. Within “The Golden House,” Rushdie attempts to capture the cultural, political, and social zeitgeist of the Obama years too broadly, stretching each aspect too thin, and the result is a novel that would have been better off addressing fewer issues in a more focused manner. Additionally, Rushdie’s allusions occasionally lose their beneficial properties and become either too varied or too obscure. At one point in the novel, Rushdie describes a garden as “the setting for a Japanese ghost story, Ugetsu, perhaps, or Kwaidan.” “The Golden House” has important things to say about the current state of politics and culture in America, but they can get lost in a sea of references to Greco-Roman mythology, European and Asian mysticism, film history, and East Asian folktales.

Ultimately, “The Golden House” is a project of great ambition and scale, and one that, for the most part, lives up to that ambition. The decline of the Golden household represents an impressive microcosm of the larger events that shaped American society over the past eight years. In the end, Rushdie gets his dramatic voyeuristic masterwork, as does René: One tracks the tragic exploits of a group of estranged family members, gradually insulating themselves over petty differences, and the other makes a film about the Golden House.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.