News

Harvard Researchers Develop AI-Driven Framework To Study Social Interactions, A Step Forward for Autism Research

News

Harvard Innovation Labs Announces 25 President’s Innovation Challenge Finalists

News

Graduate Student Council To Vote on Meeting Attendance Policy

News

Pop Hits and Politics: At Yardfest, Students Dance to Bedingfield and a Student Band Condemns Trump

News

Billionaire Investor Gerald Chan Under Scrutiny for Neglect of Historic Harvard Square Theater

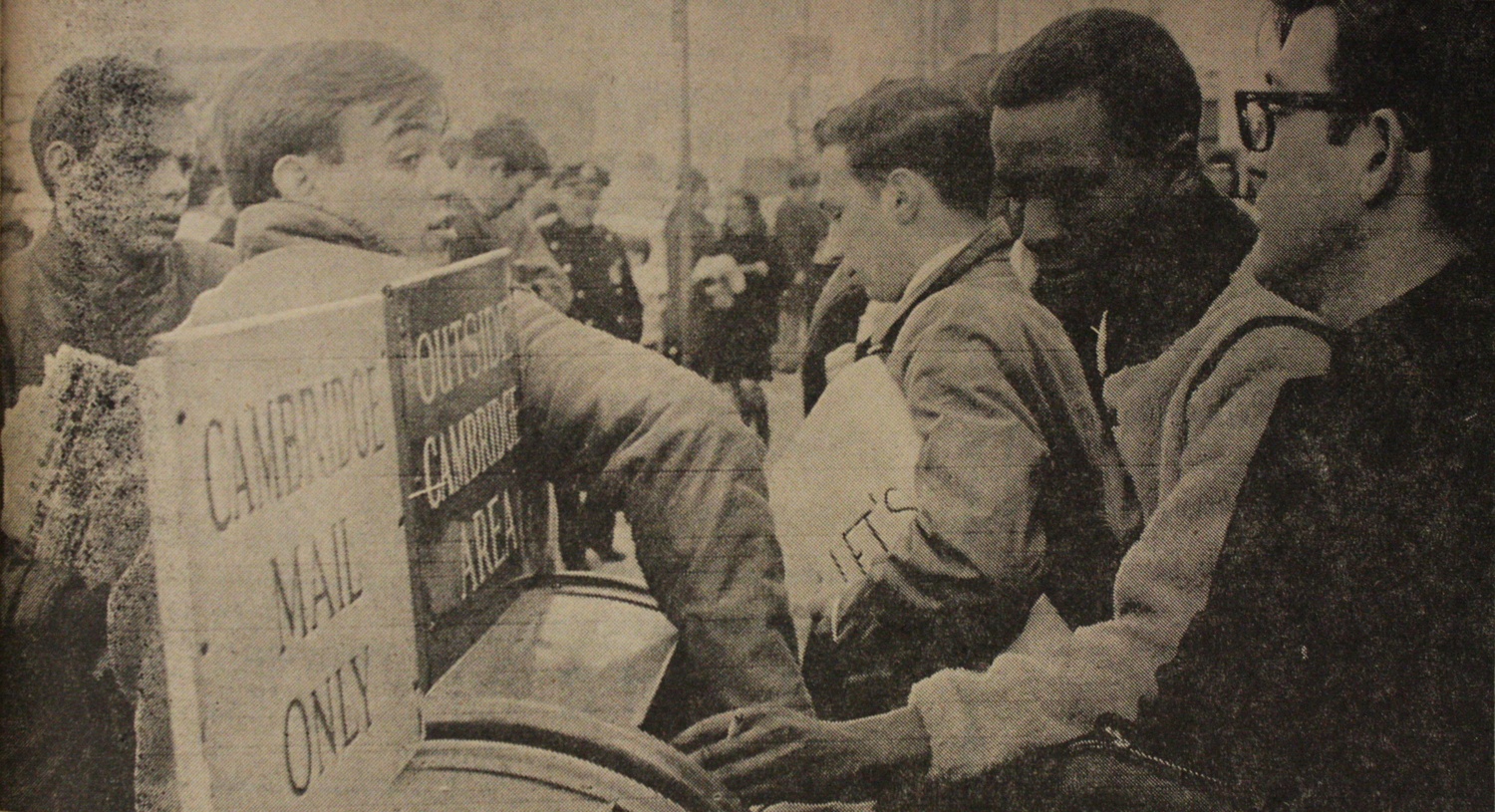

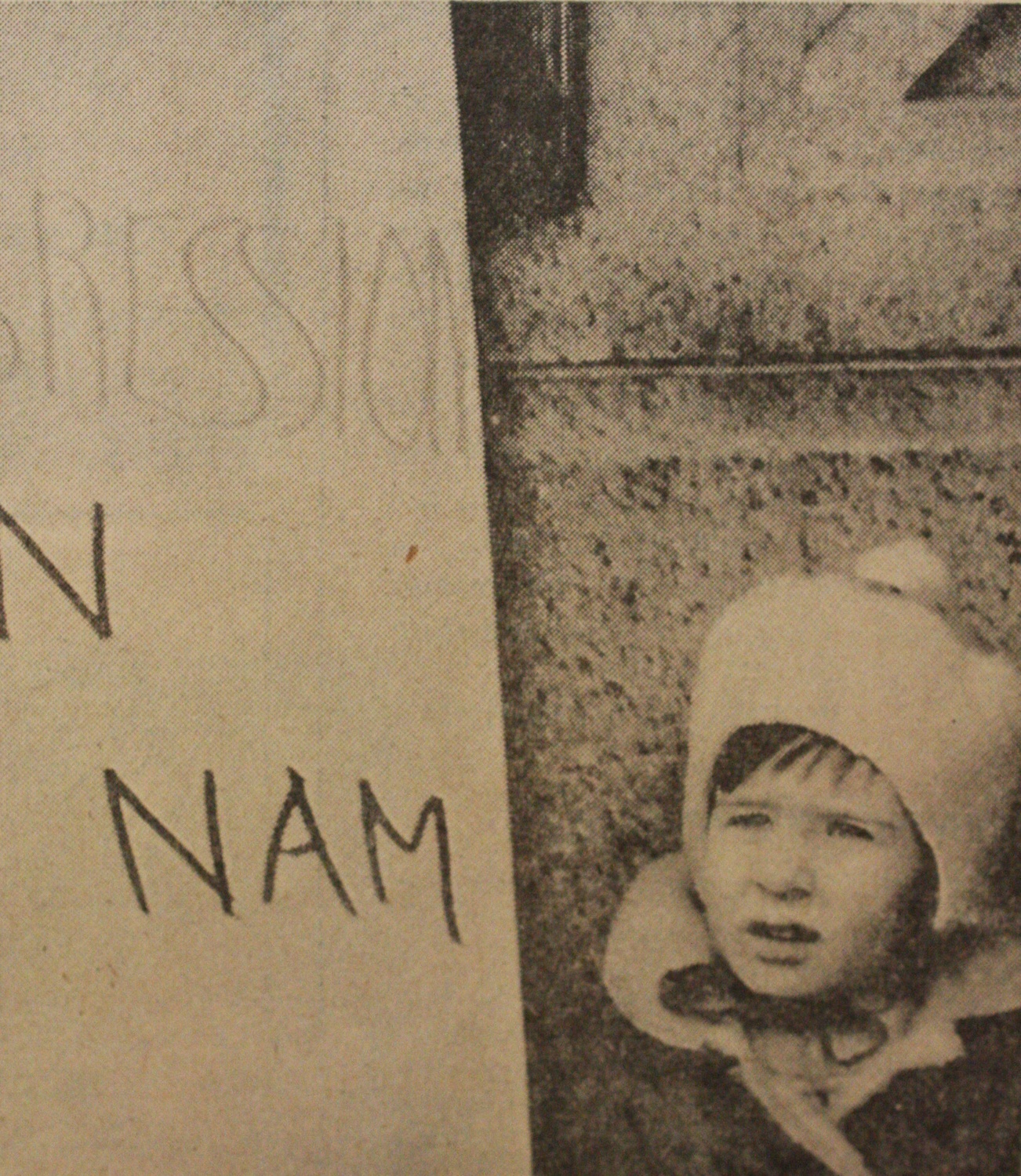

The Whispers of a Movement

Harvard Students Protest the Vietnam War

As a senior at the College organizing demonstrations against the Vietnam War, David M. Kotz ’65 faced both physical and ideological opposition from his fellow students.

According to Kotz, who presided over the Harvard chapter of Students for a Democratic Society—a national student activist organization—he and his protesting colleagues confronted insults and dodged water balloons hurled from the windows of freshman dorms.

Yet when Kotz returned four years later in 1969 as an alumnus to support ongoing anti-war protests, he recalled students shouting words of encouragement instead.

During his time at the College, Kotz rallied and marched when the U.S. had demonstrated increasing engagement in the region. In 1964, Congress enacted the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, giving then-President Lyndon B. Johnson broad authority over U.S. involvement in the war between North and South Vietnam. Johnson also approved the sustained bombing campaign of North Vietnam, known as Operation Rolling Thunder, in Feb. 1965.

The change in student reception that Kotz recalled marked a large uptick in anti-Vietnam War beliefs on campus—one that parallelled changing sentiments across the country. In April of 1969, this culminated in the student takeover of Harvard’s University Hall, which resulted in 13 students being asked to withdraw from the University and more than 100 others facing administrative consequences.

Prior to this changing wave of support, however, protesters in the ’64-65 academic year laid the foundation for the anti-Vietnam War student movement that came into fruition during the latter half of the decade.

A NATURAL PROGRESSION

In its initial stages, the anti-Vietnam War movement attracted those at the College who had previously engaged in other political causes and who drew upon their earlier experience in their anti-war activities, according to its on-campus leaders.

During her freshman year, C. Quentin Davis ’65 joined Tocsin—a student organization founded in 1960 that called for nuclear disarmament in the midst of the Cold War.

Although Tocsin disassembled about four years later, the group was considered to be “far and away the most vigorous and dynamic student political group in Cambridge,” according to an article in the 1965 Harvard yearbook by former Crimson managing editor Hendrik Hertzberg ’65.

The radical politics of the group served as a springboard for the anti-Vietnam War movement that manifested in Davis' senior year and paved the way for a Harvard chapter of SDS.

Kotz and Peter Orris ’67, both former presidents of the Harvard chapter of SDS, said they participated in the Mississippi Freedom Summer in 1964, where they forged connections with other activists.

For her part, Davis said she was influenced by her parents’ involvement in the Civil Rights movement growing up as well as her previous work with Tocsin. This interest in student activism eventually led to her briefly considering dropping out of college to protest the Vietnam war.

Though Davis decided to stay until graduation, she said that she and many of her activist peers would reflect back on past movements, including the Civil Rights movement, as inspiration for their tactics.

“The Civil Rights movement was a great influence [on the Vietnam War protests],” Davis said. “[Civil Rights activists] taught us with their blood and their weeks, months, years in jail...We learned a lot from them.”

GAINING SUPPORT: AN UPHILL BATTLE

Two student organizations, SDS and the May Second Movement (M2M), spearheaded the the anti-Vietnam War movement on campus. According to Orris, however, support was fairly minimal at the time.

“Students who were involved in these activities were really far out on the left and really a small minority,” Orris said.

Cort B. Casady ’68, a sympathizer with the anti-war movement, echoed Orris’s sentiment.

“When we started at Harvard in 1964, the movement was small,” Casady said. “America hadn’t really awakened to the realities of the war.”

However, Kotz remembered the first appearance of the anti-war movement at Harvard as a series of Crimson articles published by Kathie Amatniek Sarachild ’64 in 1962, which sparked “a lot of debate on campus.”

Though members of the Harvard community regarded Sarachild as “a crazy communist,” according to Kotz, the information she produced was widely known and accepted within a few years.

The Harvard chapter of SDS also played a role in one of the earliest national student anti-war demonstrations. Five SDS chapters at colleges nationwide organized a March on Washington on April 17, 1965, with more than 200 Harvard students participating.

According to Kotz and Orris, their initial expectation of 10,000 participants was far exceeded by the actual turnout.

“It was an extremely empowering experience...people, white and black, mostly young people, demanding basic change in society,” Kotz said. “Participating in the Mississippi Freedom Summer had changed the course of my life to being an activist for social change. That demonstration cemented it.”

The years 1964 and 1965 brought several anti-war protests, picketing actions, and teach-ins on Harvard’s campus and in the greater Cambridge community. M2M handed out weekly news pamphlets, which brought further attention to the student activists. Although there were also active pro-war protestors, their participation became more and more infrequent as the anti-war movement progressed, according to Casady, as it became increasingly difficult to defend the war.

“We weren’t saying ‘we’re right, you’re wrong,’” Davis said. “We just have humanity’s interest at heart and this war is wrong.”

LOOKING FORWARD

The protests and marches in 1964 and 1965 were merely the beginning of a movement that would continue into the late ’60s and early ’70s.

“It was a very emotionally charged time, I would say, because it was clear that the war was raging on,” Casady said. “It went on for a number of years after we graduated.”

Now-Harvard alumni who were students at the time pointed to a few events that contributed to the potential rise of student support during their time at the College. For Wayne L. Cole ’68, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination a month before he was slated to speak at the graduation ceremony for the Class of 1968 politicized the student body to rise up in solidarity.

Orris said the rise in media and news coverage of the Vietnam War largely played into the increase in student support. He added that seeing the battle on television in particular provided a sense of urgency because “for the first time, [the war] was real.”

“When people found out that the truth [of what was happening in] Vietnam was more or less the opposite of what the government was saying, it radicalized young people,” Kotz said. “There was really kind of a revolutionary mood. People had gradually come to the position that American society was unjust.”

As the years progressed and the war in Vietnam escalated, the student anti-war movement also started to take off from its initial 1965 vantage point.

“It was an exciting time be at Harvard,” Cole said. “It was a time of social awakening.”

— Staff writer Annie Schugart can be reached at annie.schugart@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @AnnieSchugart.

— Staff writer Yehong Zhu can be reached at yehong.zhu@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @YehongZhu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

Related Articles

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

Where you should have gotten your protein since 1998.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

HUSL seeks to create and empower a community of students who are seeking pathways into the Sports Business Industry.