News

Garber Privately Tells Faculty That Harvard Must Rethink Messaging After GOP Victory

News

Cambridge Assistant City Manager to Lead Harvard’s Campus Planning

News

Despite Defunding Threats, Harvard President Praises Former Student Tapped by Trump to Lead NIH

News

Person Found Dead in Allston Apartment After Hours-Long Barricade

News

‘I Am Really Sorry’: Khurana Apologizes for International Student Winter Housing Denials

HSA-Run Charter Flights Flew High Over Allegations

In 2014, Harvard Student Agencies, Inc.—the multi-million dollar student-run company founded in 1957—came under scrutiny when student-run food delivery service InstaNomz shut down after a little more than a month of operating. According to InstaNomz’s founders Akshar Bonu ’17 and Fanelesibonge S. Mashwama ’17, the Office of Student Life informed them they either had to assume an outside vendor status and lose internal dorm delivery privileges or work under HSA.

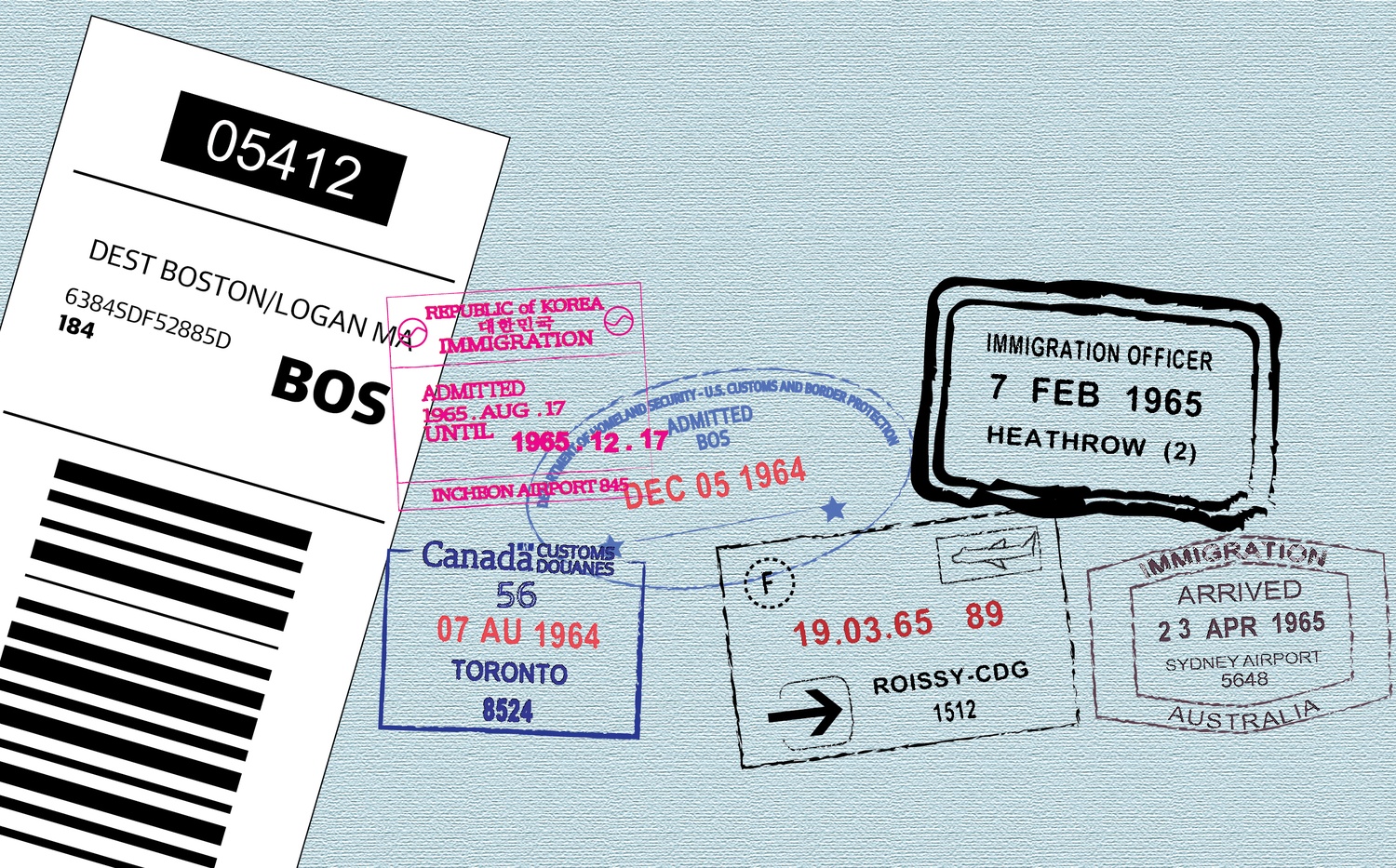

The occurrence led some students to criticize what they describe as HSA’s monopoly status granted by the University. The contemporary episode heralded back to HSA’s earlier days, when students in Feb. 1965 accused the organization of abusing its monopoly status by charging exorbitant prices for its charter flight service. Following a University investigation of HSA’s flight services, the University concluded that it was “entirely satisfied with the HSA operation.”

However, criticisms of HSA’s transparency and business practices from members of the student body abounded in the period between the University asking HSA to prepare “a complete report” on its charter flight services and its decision that reaffirmed HSA’s monopoly.

BEGINNING YEARS

In Harvard Student Agencies’ early years, its premier charter flight business organized up to 15 flights for Harvard students from Boston to various cities in Europe, including London, Paris, and Athens, according to Bradlee T. Howe ’63, a former HSA general manager who managed its charter flight agency in his senior year.

“I was working at just the sixth year of HSA’s existence, so it was still in some ways a fledgling organization, but we managed to run it, at least in ’63, while serving the Harvard community in very good order without any significant complaints about mixing up flights or not having seats for people or so forth,” Howe said.

Howe added that the 15 flights scheduled to Europe for the summer of 1963 were mostly through British Overseas Airways Corporation, with one Swiss Air flight, which HSA arranged through then-Harvard Square travel agency, University Travel. Exclusive to Harvard students, faculty, and alumni, the flights costed about $230 to $250 round trip.

Of note, HSA claimed a University-mandated monopoly on charter flights.

“There was a prescription about operating businesses from student dorm rooms, and the University was very conscious of not contravening that law and thereby making University property taxable as for unrelated business income,” Howe said. “The University...tended to funnel most business opportunities through the HSA.”

Howe also recalled that the business continued through the holidays and was generally well received by the Harvard student body. In fact, Columbia University modeled its own flight agency off of Harvard’s, according to an archived February 1965 issue of the Columbia Spectator.

MONOPOLY UNDER ATTACK

In February 1965, College students claimed that HSA’s flight prices were too expensive, costing more than those of the year prior and those of other universities like Columbia, allegedly resulting in exorbitant profits for the agency.

According to Crimson coverage at the time, BOAC unexpectedly terminated most of its charter operations, leaving HSA to make last minute negotiations with other airlines at inflated prices.

In response, Dean of Students Robert B. Watson, Dean of the College John U. Monro ’34, and administrative vice-president L. Gard Wiggins asked HSA to submit a report of its flight operations for review, with Wiggins ultimately deciding whether HSA should keep its at the time seven-year monopoly on charter flights or whether it should re-establish the competitive system.

In the interval period before the report was prepared and submitted, Stephen A. Sohn ’66 and Stephen Walters claimed they could organize charter flights to London and Paris, respectively at $240 and $260, for less than what HSA was charging, The Crimson reported.

However, once the administrators reviewed the report and deemed the prices “indeed reasonable and proper” at the end of February 1965, the University reiterated its decision to enforce HSA’s monopoly. To monitor the agency, a committee was formed to review their accounts once yearly.

The details of the report, and the agency’s figures, were not released to the public. Watson at the time declined to discuss details of the report “because if you release figures there are questions, and if you release more figures to answer the questions there are more questions, and soon all the figures are out.”

“They’re meaningless unless you have someone to explain them,” Watson said at the time.

With its monopoly reaffirmed, HSA subsequently rejected Sohn’s proposed cheaper flight out of fear that it would drain passengers from its previously chartered planes, and because HSA preferred to conduct business only with a single travel agency, University Travel, according to the Crimson archives. Sohn claimed at the time his offer was “reasonable and rational.”

“If charter flights are for the benefit of the students, this benefits the students completely,” Sohn said at the time.

Even with administrators taking action to address student allegations, College students did not voice complete satisfaction. “The International Air Transport Association requires that prospective passengers be given estimates of expected costs and that detailed financial statements be issued after every flight. Whether or not the HSA believes itself exempt from these regulations...it has an obligation to the community to furnish the information,” read the Crimson.

VESTIGIAL WINGS

Although the business eventually crumbled with the decline of commercial airline flight prices, the charter flights operation has left a mark on the agency and on Harvard in the form of the HSA’s travel guide series, ‘Let’s Go.’

“The charter flight was a mainstay of the HSA, and in 1961 it spawned the ‘Let’s Go’ guides, which essentially became the mainstay of the HSA, and it was all part of the growth of the agency,” Howe said.

Patrick F. Scott ’16, current HSA president, also emphasized the role the charter flights had in forming the travel guide series.

“Eventually, some students realized that the people on these flights were getting to Europe and they didn't know what to do once they got there, so they started handing out pamphlets on the flights to Europe,” Scott said. “The ‘Let's Go’ series has survived to this day and still publishes a Let's Go: Europe book, written by Harvard students, annually.”

— Staff writer Ben Cort can be reached at ben.cort@thecrimson.com.

— Staff writer Jiwon Joung can be reached at yuna.joung@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @yunajoung

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.