News

Harvard Researchers Develop AI-Driven Framework To Study Social Interactions, A Step Forward for Autism Research

News

Harvard Innovation Labs Announces 25 President’s Innovation Challenge Finalists

News

Graduate Student Council To Vote on Meeting Attendance Policy

News

Pop Hits and Politics: At Yardfest, Students Dance to Bedingfield and a Student Band Condemns Trump

News

Billionaire Investor Gerald Chan Under Scrutiny for Neglect of Historic Harvard Square Theater

A Debate on Housing

Year saw early pushes toward House randomization

Students were divided. House masters were conflicted. Associate Dean of the College of the House System Thomas A. Dingman ’67, however, was sure.

Starting in 1988, Harvard’s administrators debated a major alteration to the University’s House system. Originally created in the 1920s and later tweaked in the 1960s, the housing system was leading to “preppy ghettos” and racially imbalanced communities by 1988-1989.

Still, a group of House masters were reluctant to change the system. Dingman was only fully convinced change had to happen after reading a letter penned by a recent graduate, who wrote about the flawed House system.

The student, an athlete, had moved into an upperclassman House with everyone on his team—a common phenomenon as athletes were often assigned to the same House. The teammates spent every minute of the day together, practicing on the fields across the river, eating meals at the same dining hall table, and even attending classes together since they were all disproportionately studying economics.

As graduation drew near, the student noticed that his social circle had grown more and more insular. Looking back on the four years he spent at Harvard, the student wrote that he was disappointed that he got to know so little about his peers across the class.

“This made us wonder if we were really educating people for the lives they were going to have after college,” Dingman says. “We knew we had to change the system.”

Ultimately, the change would only be a temporary step in a process that would take years to conclude. But the debate over housing in 1988-89 represented one of many battles as an increasingly diverse University attempted to modernize.

HISTORY OF THE HOUSING SYSTEM

The debate embroiling campus in the late 1980s was far from the first surrounding the University’s housing system.

When then-President Abbott Lawrence Lowell structured and implemented the Harvard housing system in the late 1920s with the idea that each of the 13 Houses be a “microcosm” of the College, the elites complained about mixing with others, The Crimson called the plan arbitrary and disrupting, and freshmen were concerned about their future.

From the inception of the system in 1920 to 1967, the housing system was structured such that 75 percent of the entering upperclassmen were hand-selected by the House masters, while only 25 percent were randomly assigned a House.

“It was a bit scary to go and be interviewed by the distinguished old House masters,” remembers Howard M. Georgi ’68, the current Leverett House master.

The system was first modified in the late 1960s. It was a period of great student unrest and a time when students “did not trust any faculty, any administrators...or anyone over thirty,” says Biology professor John E. Dowling ’57.

The students demanded that the system change, leading to the creation of the ordered choice system, in which students ranked their top housing choices and received a lottery number that determined their assignment.

This system worked well and the Houses continued to be diverse and “essentially a microcosm of the College,” Dowling says.

It was not until the early 1980s that certain Houses began attracting specific groups of students, so that by the mid-1980s the College began to see certain groups of people in different Houses.

“That was disturbing,” says Dowling, who became the Leverett House Master in 1981.

“All the African-American students were in one or two Houses, all the gays and lesbians were in one House, and all those that either came from prep schools or thought they should have been coming from prep schools were in another House,” he says. “Then all the athletes were heading to yet another House, and the science concentrators to yet another House.”

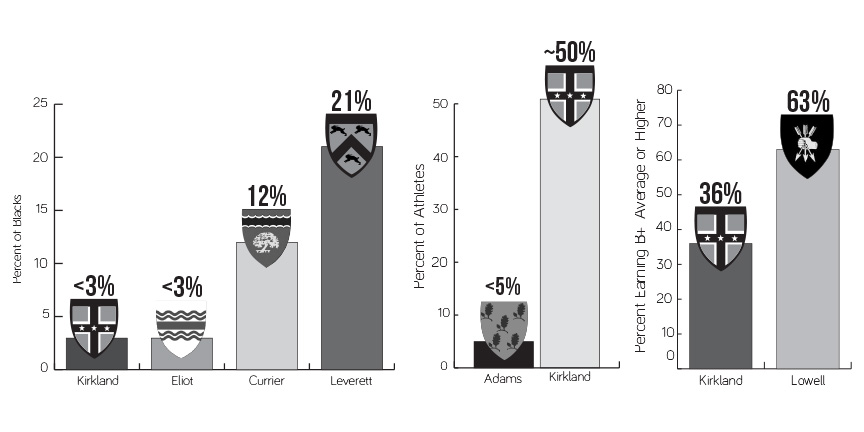

A study done in 1982 found that African Americans made up 21 percent of Currier House compared to less than three percent of Kirkland and Eliot Houses. The study also showed that athletes made up just under half of Kirkland House, while they made up only five percent of Adams House.

“When I returned to Harvard as a post-doc in 1971, the old system had been swept away, and replaced by the pre-randomization system” Georgi says. “I think that this was a disaster for Eliot House. It had become a preppy ghetto, and I could not find the diversity of students that I had so enjoyed as an undergraduate a few years earlier.”

HOUSE MASTERS DEBATE

In December 1987, Dingman first mentioned the issue of House segregation in a House committee meeting, and in March of 1988 the House masters first debated the issue.

The masters were divided. Those that were against the proposed change argued that pure random assignment would “take away the real energy,” Dingman remembers. They were worried that if, for example, a House that had been known for putting on theatrical productions no longer had this distinction, then no House would be able to mount anything of the sort.

“But we knew this wasn’t true,” Dingman says, “because a House at the time was winning the Strauss Cup—an award for intramural success—and this House had been randomly assigned… This same House was also putting on its own in-House musical.”

Other House masters, like Dowling, pushed for change.

“We think every House should be a microcosm of the College, and that the students can learn as much from one another as they can from us faculty. If it’s all the same in every House, it would really be a mistake...we would be negating what Lowell set up as the ideal House system.”

The students were also divided. Some thought that this “social engineering” would ruin Harvard, while others thought it would provide for a richer undergraduate experience.

According to Dowling, an Undergraduate Council survey showing mixed feelings on the issue helped encourage the House masters to move forward.

By June of 1989, the housing administration resolved that they had to adjust the lottery system, and the non-ordered choice system, in which students could list four choices but not rank them, was implemented on a trial basis. The new system was the result of a compromise among some students who wanted to retain ordered choice and many House masters who insisted on fully random housing allotments.

HOUSING TODAY

In 1993, the House masters noticed that the Houses were continuing to have imbalances under the non-ordered choice system, and three years later, in the Spring of 1996, switched to complete randomization to promote greater diversity.

When the new procedure was first announced, 82 percent of the student body opposed the change. Dingman says that in the year following the transition to complete randomization, “it was problematic, because if you were a House that prided yourself on being athletic, then those rising sophomores that now had no interest in athletics felt it was a funny fit.”

In quick order, however, “it was not a problem,” Dingman says.

House surveys showed that House system satisfaction rose in the years after the shift to random assignment.

“I think it’s a much better system,” Dowling says.

—Staff writer Joanie D. Timmins can be reached at jtimmins@college.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.