News

News Flash: Memory Shop and Anime Zakka to Open in Harvard Square

News

Harvard Researchers Develop AI-Driven Framework To Study Social Interactions, A Step Forward for Autism Research

News

Harvard Innovation Labs Announces 25 President’s Innovation Challenge Finalists

News

Graduate Student Council To Vote on Meeting Attendance Policy

News

Pop Hits and Politics: At Yardfest, Students Dance to Bedingfield and a Student Band Condemns Trump

Liquor Licenses Prove Critical for Local Restaurants

When Jose Sahagun opened the doors of Cancun Taqueria y Mas last October, customers constantly demanded margaritas. But Sahagun was still waiting to obtain a liquor license and, without one, he worried that the new restaurant might fail before it could gain a foothold among Harvard Square businesses.

Other business owners have echoed the same story. They too experienced frustration and delays while they waited to receive a license. Often, the process of obtaining such permits can be long and arduous. Some Massachusetts liquor laws date back to the eighteenth century, and today, there is a myriad of rules surrounding the application process.

Yet despite the high costs and intricacies of applying, business owners are often willing to wait weeks, wading through multiple levels of red tape, to obtain a permit. Many say that liquor licenses often make the difference between sinking or swimming.

GETTING LICENSED

Restaurant owners who wish to obtain a new license are sometimes forced to wait months while they complete the lengthy application process instituted by the Cambridge License Commission.

For Sahagun, the owner at Cancun Taqueria, the process involved multiple hearings before the Cambridge License Commission. Cancun also had to present a petition with over 1,000 signatures of support and complete a series of exhaustive background checks before its application moved forward.

The whole process took six months total.

“It was a very long, difficult process. Every step along the way was difficult,” Sahagun said.

Elizabeth Y. Lint, executive director of the Cambridge License Commission, however, noted that the liquor license process stands apart from that of other areas of Massachusetts. According to Lint, Cambridge is one of only two Massachusetts counties that lack a fixed quota for liquor licenses.

Though there is a quota for the number of liquor stores around Harvard Square, no such limit exists for liquor licenses given to restaurants, Lint said. She said she believes that the number of eateries to successfully obtain licenses has increased in recent years, especially due to development in Kendall Square. Meanwhile, the number of Harvard Square restaurants that have received licenses has held relatively steady over the last several years, she said.

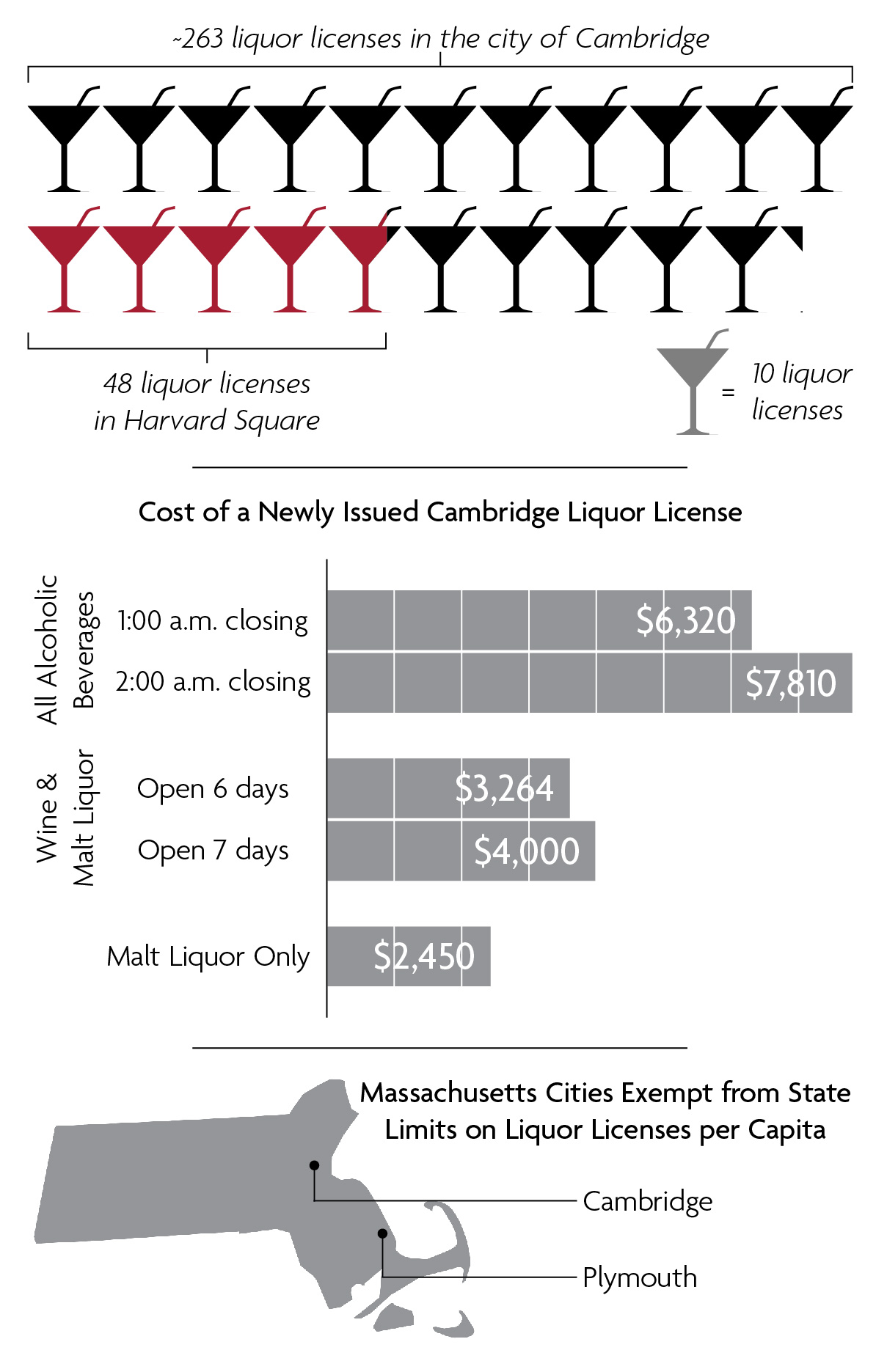

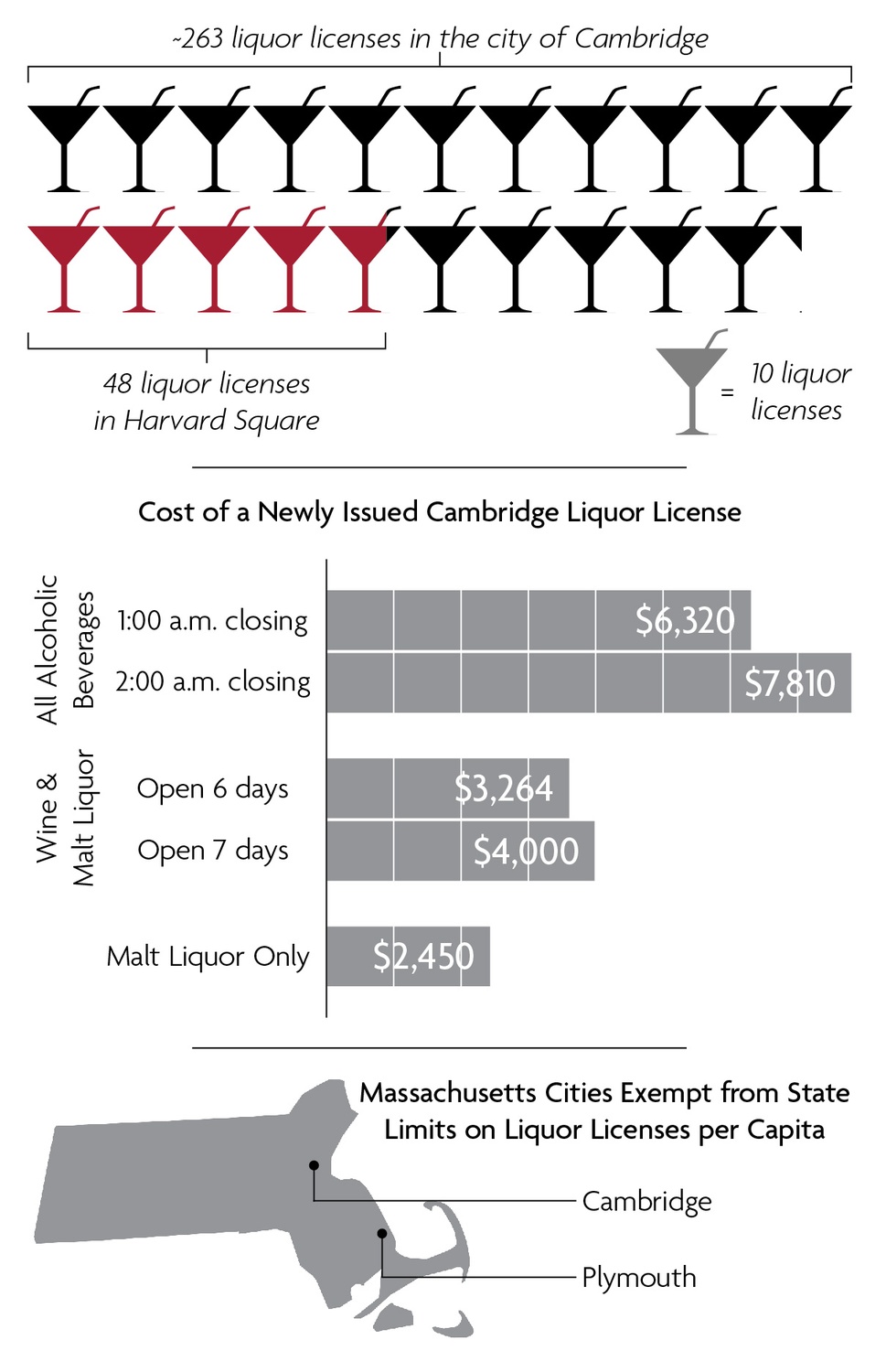

Lint estimated that about 263 establishments currently hold liquor licenses throughout Cambridge. According to Denise A. Jillson, the executive director of the Harvard Square Business Association, only 48 of those liquor licenses currently belong to restaurants in Harvard Square.

To obtain the coveted license, those restaurants had to undergo a rigorous and costly application process, with most applicants paying an initial $175 “hearing and advertising” fee to set the wheels in motion. They must also pay an additional $200 state fee.

Stores seeking to sell various types of alcohol or remain open at different times receive specific types of license—each with its own fee.

Lint outlined the manifold varieties of licenses available and the restrictions that they entail.

“You can have just wine and malt, you can have all alcohol,” Lint said. “There are some that are just breweries, like Cambridge Brewing Company, and then the hours are different, the days of the week might be different.”

According to Lint, the most expensive licenses can cost around $6,000. Restaurants are often willing to pay the extra sum because the more expensive license comes with greater freedom to sell what they want, when they want to.

Lint estimated that the process for issuing a new license could take anywhere from four to ten weeks, depending on whether there are issues with state compliance.

Although owners reported a variety of experiences regarding the licensing application, most noted that obtaining a liquor license can make or break an establishment—particularly in Harvard Square.

CERTIFICATE FOR SURVIVAL

According to Sahagun, when Cancun Taqueria opened its doors in October 2013, it became immediately apparent that a liquor license would be required for the business to turn a profit.

He recounted how customers constantly asked whether the restaurant served trademark Mexican drinks, such as margaritas, before Cancun Taqueria acquired its license.

“It’s very important, especially in the area,” Sahagun said. “People want to have Mexican food with a drink. If we didn't [serve alcohol], they would just not come, and that’s one of the problems we ran into.”

After acquiring a liquor license about a month ago, business at the Taqueria improved dramatically, Sahagun said.

Many other Cambridge establishment owners offered similar perspectives, highlighting the importance of a liquor license.

Dan B. Hogan, executive director at the folk music venue Club Passim, noted that although he had no difficulty obtaining a special non-profit liquor license, the permit has proved critical to his business. According to Hogan, beer and wine sales account for almost 100 percent of its surplus revenue.

For restaurants, the necessity of a liquor license is even more acute.

Jen Fields, the general manager at Alden & Harlow, said that it is easier to make money from alcohol sales than from food. She noted that the perishability of food was one reason why alcohol generally produces wider profit margins.

Kari Kuelzer, the co-owner and general manager of Grendel’s Den, also highlighted how restaurants need licenses to make a profit.

“The general rule of thumb is that if they don't serve alcohol, they won't survive,” Kuelzer said.

MAKING DO WITHOUT

Though liquor licensing can provide a boost to revenue, many businesses still yield a profit without a liquor license.

Felipe’s Taqueria, for example, operated without a license to distribute alcohol at its former Mt. Auburn location for almost a decade.

Yet even that popular vendor has succumbed to the need for a license. The restaurant announced plans to move to a new location and to seek a liquor license last October.

Although the owners have already begun the process of transferring business to 21 Brattle St., they are unsure when they would receive a license any time soon. According to co-owner Tom Brush, the application process has taken longer than expected. He now plans to open the new location without a license.

Yet Brush said he was unconcerned.

“While we would love to open with a beer and wine license, it’s unlikely that we will,” Brush said. “Felipe’s has always been about the food and we’re not concerned about operating and opening without a liquor license.”

Jillson agreed that a liquor license is sometimes unnecessary and pointed to a wide range of flourishing eateries without licences in Harvard Square.

According to Jillson, some establishments simply do not require alcohol sales to bolster their business model. She also noted that some fast food restaurants, such as Flat Patties and Pinocchio’s, do not offer an environment conducive to serving alcohol.

Nevertheless, Jillson reaffirmed the importance of a liquor license for restaurants, which offer a more traditional setting.

“If their vision includes sitting down and having a nice meal and a glass of wine or cold beer as part of that experience, then yes, [a license] is absolutely critical,” Jillson said.

—Staff writer Ivan B. K. Levingston can be reached at Ivan.Levingston@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @IvanLevingston.

—Staff writer Celeste M. Mendoza can be reached at Celeste.Mendoza@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @CelesteMMendoza.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.