News

Harvard Quietly Resolves Anti-Palestinian Discrimination Complaint With Ed. Department

News

Following Dining Hall Crowds, Harvard College Won’t Say Whether It Tracked Wintersession Move-Ins

News

Harvard Outsources Program to Identify Descendants of Those Enslaved by University Affiliates, Lays Off Internal Staff

News

Harvard Medical School Cancels Class Session With Gazan Patients, Calling It One-Sided

News

Garber Privately Tells Faculty That Harvard Must Rethink Messaging After GOP Victory

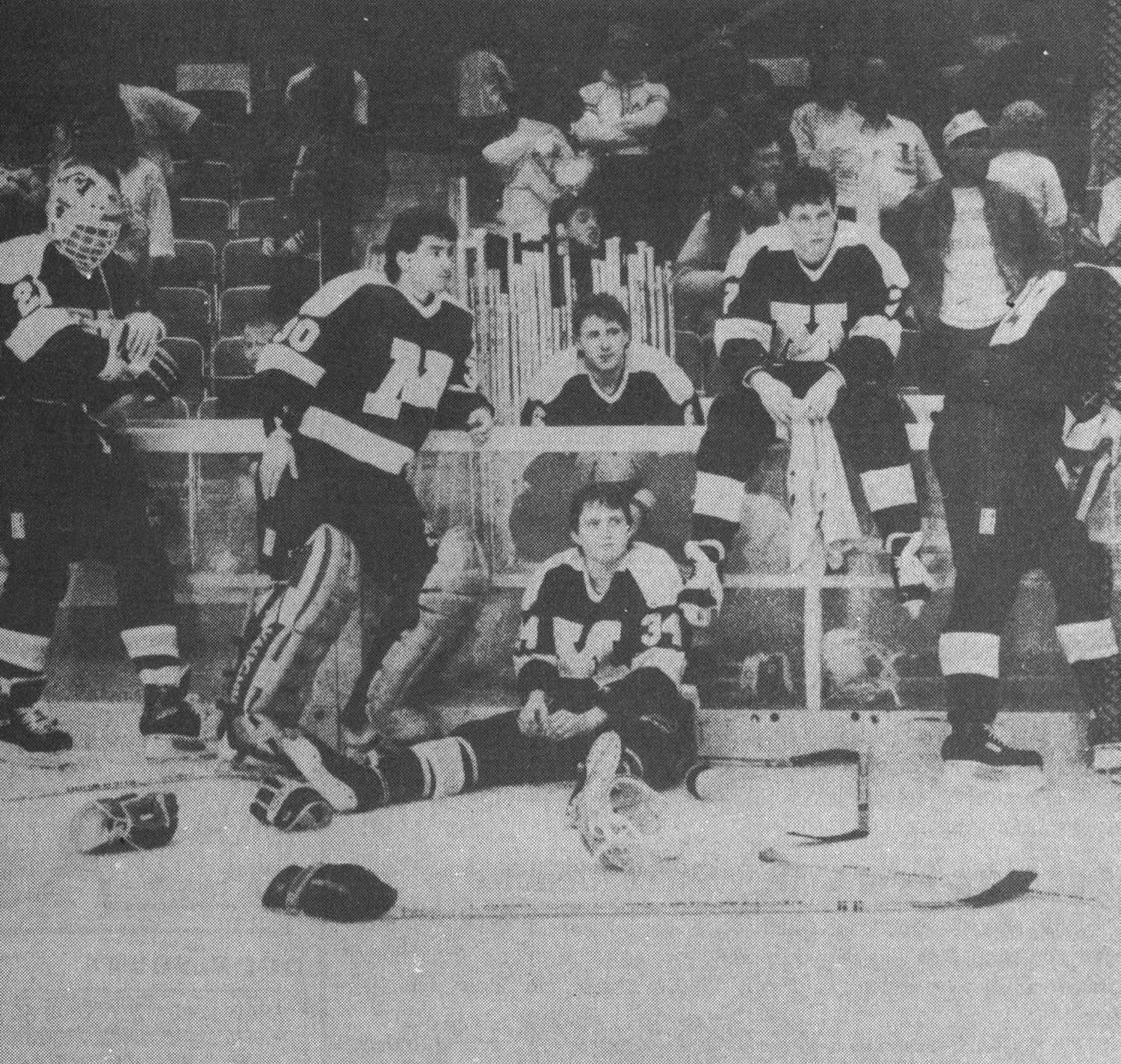

Harvard Hockey 1989: A Championship in Perspective

From his perch upon a coffee table, Bill Cleary ’56 held a tall wooden trophy as he addressed the hundreds of Crimson alumni, players, and fans gathered in the lobby of the St. Paul Hotel.

“This isn’t just for the hockey team,” pronounced the balding coach as he bared his dentures through a youthful grin. “This is for every Harvard alumnus in the country—in the world.”

On that fateful April Fool’s Day 25 years ago, Cleary was speaking before the most exuberant audience in the Land of 10,000 Lakes.

After all, the Harvard men’s hockey team had sent the rest of the state into mourning only a couple of hours earlier.

The mood inside the lobby could not be more different than the one outside it. Until that night, the oldest athletics program in the country had yet to win a national championship in an NCAA team competition.

A slow-sliding backhand shot from junior forward Ed Krayer ’89-90 had ended the wait, lifting Harvard over the University of Minnesota for a 4-3 overtime win to capture the 1989 national championship. For the first time in the Association’s 83-year history, Cambridge could finally claim a champion as its own.

Twenty-five years later, Harvard has since added three more NCAA team titles to its name, but none in a major American professional sport. Not until the 2013 Yale Bulldogs did another Ivy League team win a men’s national hockey title. Indeed, the trophy in Cleary’s hands was unlike any other prize a Crimson coach had held before or has held since. And it was there for all to see in the lobby of the St. Paul Hotel thanks to a delicate balance of leadership, talent, and luck.

SETTING THE TONE

Lane MacDonald ’88-89 stood up to face his teammates. It was late September in Allston, and a feeling of anticipation was in the frigid air of the Bright Hockey Center as the Harvard icemen sat for their first official meeting of the 1988-1989 season.

An impressive collection of individuals sat before the left winger. There was sixth-year senior Allen Bourbeau ’88, who had taken the previous year off with MacDonald to play for the 1988 U.S. Olympic team. There were four future Olympians in the group: junior right wing C.J. Young ’90, sophomore forwards Peter Ciavaglia ’91 and Ted Donato ’91, and freshman goaltender Allain Roy ’92. All told, 15 NHL draft picks sat before MacDonald, a Hartford Whalers prospect himself.

MacDonald was the obvious choice to captain the team in his senior year. Although the former Milwaukee prep star was one of the quieter guys on the team, he knew how to communicate to his teammates through action. His speed and offensive prowess were matched only by his impeccable work ethic.

“When the best player is also the hardest worker, everyone else tends to fall in line,” says Scott Farden ’88, a senior defender on the team and the current chair of Friends of Harvard Hockey. “That’s how Lane led.”

MacDonald’s 37 goals—second only to Cleary on the program’s all-time list—and nomination for the Hobey Baker Award, hockey’s equivalent of the Heisman, in his junior season spoke for themselves. At this first team meeting, however, it was clear that the captain had something to say. And when MacDonald had something to say, you listened.

“Anything less than a national championship is unacceptable this year.”

The captain’s statement was both bold and realistic. Bold in the sense that “anything less than a national championship” was the norm for Harvard as an institution. Then-athletic Director Jack Reardon ’60 expected the hockey team to compete for Ivy League championships—not NCAA championships or even ECAC championships. But MacDonald’s ambitions were far from unrealistic, especially given the events 29 months earlier.

For eight players on the ’89 team, the memory of 1986 still burned. Late in the second period of the 1986 national championship game in Providence, R.I., the Crimson had held a 4-2 lead over Michigan State. Despite the absence of MVP senior forward Scott Fusco ’86, who had suffered a knee ligament strain in Harvard’s semifinal win over Denver the day before, the Crimson, who held a 5-4 lead with 17 minutes left, were less than a period from becoming the first Ivy League squad since Cornell in 1970 to win the title. Yet the favored Crimson would run out of steam down the stretch as the Spartans rallied to a 6-5 title win.

“We were so close, and we were playing so well,” MacDonald says. “We so easily could have won the national championship. But there’s such a fine line between losing and winning at that level.”

With MacDonald and Bourbeau back from their Olympic sabbatical, the Crimson offered more offensive firepower than ever before. While three of the last six Harvard teams had made the Frozen Four, two advancing to the championship game, the bar was set higher in 1989. From MacDonald’s perspective, the team had too much talent not to win it all.

“We had all of the pieces in place to win a national championship, so it had to be our objective,” MacDonald says. “Anything less than that we’d be selling ourselves short.”

But the captain also had a more personal reason to consider losing unacceptable: he knew what he was risking when he stepped on the ice.

The symptoms had started in high school. The numbness. The loss of vision. The struggle to turn on a shower or button a shirt. The migraines and concussions only got worse in 1988. Three weeks before the Opening Ceremonies, MacDonald seriously considered withdrawing from Team USA.

“I had enough issues that I was losing some parts of the enjoyment playing hockey,” says MacDonald, whose concussions would ultimately force him to forego a career in the hard-hitting NHL. “And honestly, there was some fear every time I played.”

MacDonald played through the fear and scored six goals in six games in Calgary, and Harvard neurologists gave him only a cautious go-ahead to play in the 1988-1989 season. His worst fears appeared to be confirmed when he experienced a concussive episode in Harvard’s opening game versus Yale, but that would end up being the worst of his symptoms that season.

Still, the nagging doubt remained throughout the year, and a focus of the Crimson’s season would be to protect the most important and most fragile piece of its championship puzzle.

MEETING EXPECTATIONS

Each game of Harvard’s season began the same way behind the bench. Cleary would offer assistant coach Ronn Tomassoni a cough drop. Tomassoni would offer Cleary a cough drop.

In 1989, the superstitious Cleary was ready to finish what he had started 34 years earlier. Before Cleary led the gold medal-winning 1960 U.S. Olympic hockey team in scoring, the Cambridge, Mass. native led Harvard to its first-ever Frozen Four in 1955 as a standout All-American forward.

“Billy Cleary is legendary,” says John “Jocko” Connolly, a long-time college hockey beat reporter for The Boston Herald. “He is so passionate about the game and such a competitor. He would just will his team to win.”

Cleary had turned down offers from the Boston Bruins and Montreal Canadiens during his time at Harvard. After graduating, he started an insurance sales firm with his brother Bob ’58, who also owns Crimson hockey records and an Olympic gold. Coaching was only a part-time gig for Cleary when he became Harvard’s head coach in 1971, and it would remain that way through 1990, when he retired from coaching to succeed Reardon as Harvard’s athletic director. The multi-tasking, however, did little to diminish Cleary’s abilities behind the bench.

“He brought an energy and confidence that definitely reverberated throughout the team,” says Donato, who is the current coach of the Harvard men’s hockey team and regularly sees Cleary at home games.

He had little difficulty getting his squads to buy into his lightning-strike, offense-minded system. Cleary earned the elusive combination of love and respect from his players that any good coach strives to achieve. Away from the rink or during Monday morning skates, he was just one of the guys. His broad arsenal of practical jokes—from canine impersonations to swapping whipped butter for ice cream on an unsuspecting Sports Illustrated reporter—kept his charges in stitches.

But when it came time to work, Cleary conducted the team with military-like precision.

“He kept it light and fun, and it was almost like a Jekyll and Hyde thing,” Farden says. “He was fun-loving and loose and jovial off the ice, but when we got on his competitive spirit came in. We didn’t waste a second of any practice.”

The focus instilled by Cleary propelled Harvard to a perfect start and a No. 1 ranking through the first 15 games of the 1988-1989 season. The combination of MacDonald, Bourbeau, and Young quickly earned the nickname the “Line of Fire” as the stars bludgeoned defenses up and down the East Coast.

When the stars were on, the results rewrote the history books. On Dec. 12, Young scored three shorthanded goals within a span of 49 seconds in a 10-0 win over Dartmouth. A month later, the team cruised to a 5-1 win over then-No. 1 St. Lawrence on the road.

“The goalie from St. Lawrence, he didn’t know what was going on,” Connolly said. “Harvard had some great games that year.”

By the second half of the season, however, some pundits had relegated the Ivy Leaguers to pretender status. An upstart Vermont squad had surprised the Crimson in overtime in the semifinals of the ECAC Tournament, and Harvard’s two regular season losses had come to mediocre Yale and Colgate teams. The Crimson’s short and relatively weak schedule raised red flags for the NCAA seeding committee, which awarded 11-loss Maine the top seed in the Eastern bracket, bumping the Crimson to the second seed.

By the time Cleary’s boys faced off against top-seeded Michigan State in the first game of the Frozen Four, few outsiders saw Harvard as the team to beat. While a hat trick from Ciavaglia had lifted the Crimson to a quarterfinals sweep of defending champion Lake Superior State at Bright a week earlier, the Crimson had yet to match up against an elite western team on the road.

In an interview with a Twin Cities paper a day before the puck drop in St. Paul, Michigan State forward Bobby Reynolds best summed up the consensus view of Harvard’s championship chances: “Thank God we’re not playing Minnesota.”

The Spartans may have gotten the match-up they wanted in the national semifinal, but they didn’t get the result. The Crimson, buoyed by first period goals from Young and Ciavaglia and an early acrobatic stop from freshman goaltender Allain Roy on a wrap-around attempt from Reynolds, downed its 1986 tormentors, 6-3, in front of a State-partisan sellout crowd.

While a small Harvard contingent celebrated at the Civic Center, hundreds of other Crimson fans rejoiced in front of televisions across the country. Among those who had tuned into ESPN was a group of about 40 Harvard football players and other students on spring break at a Daytona Beach, Fl., sports bar. Inspired, the next morning, senior defensive tackle Jim Bell, senior quarterback Tom Yohe, and eight other friends woke up early to embark on the 30-hour drive to St. Paul for the championship game.

“I remember being fueled by a combination of Cool Ranch Doritos and NoDoz,” Bell says. “I remember leaving Daytona Beach and it was about 85 degrees. Crossing the border from Wisconsin to Minnesota, it started to snow and it was about 12 degrees, and we felt that we had made a terrible mistake.”

The players made some calls to contacts in the Harvard Athletics Department during gas station stops and obtained a row of seats in the nosebleeds. Despite being flagged down for a speeding ticket in Dubuque, Iowa, Bell and his friends arrived at the St. Paul Hotel just in time to wish their friend MacDonald and his team good luck during their pre-game meal.

“For them to make the trek, and to drive that far for us, and to be very vocal supporters before the game started [and] during the game, it meant a lot,” MacDonald says. “You just knew that people were pulling for you and you had the support of...the students, the alums, and it was just a very visible symbol of how many people were pulling for us to win.”

OVERTIME

“You guys should be salivarating out there.”

The Crimson locker room erupted in laughter. The icemen were about to play the most important minutes of their careers, but they couldn’t help but laugh at Donato’s butchering of the word “salivating.”

After 60 minutes, nothing separated the nation’s top two teams in a back-and-forth championship game. A sweeping, coast-to-coast strike from MacDonald and Donato’s third goal of the Frozen Four had given Harvard 2-1 and 3-2 leads during the contest, but Minnesota quickly found an answer each time. With just 3:26 left in regulation, Golden Gopher left wing Peter Hankinson had tied the game at three on the power play.

“That couldn’t have been a better-played hockey game,” Farden says. “There was so much talent, and it was pure, there was skill on display…. Both teams took turns dominating the game.”

As the Zambonis resurfaced the ice before hundreds of tense Minnesotans, Donato did his best to keep himself and his teammates loose by shouting out the ridiculous pump-up line. The malapropism cracked up freshman goaltender Chuckie Hughes, Donato’s old high school teammate.

“Everybody just lost it at that point,” Hughes says. “It was a nice mood-breaker to kind of get so [we’d] be a little less tight going out into the overtime.”

Hughes had saved 31 of the 34 shots that came his way in the first three periods. Heading into sudden death, he could not envision another puck getting by him.

“Chuckie was a very confident guy and very clutch,” Donato says. “There certainly were no moments where he didn’t feel like he was capable of being up to the task.”

The atmosphere was also light in the Minnesota locker room before overtime. The Golden Gophers resembled the Crimson in many respects. Like Harvard, they had returning Olympic talent in junior Dave Snuggerud, an offensive-minded coach in Doug Woog, and a Hobey Baker winner in senior goaltender Robb Stauber.

Minnesota also had another player in the locker room who, like Hughes, was brimming with confidence. Junior defenseman Randy Skarda felt that he was due.

“I remember telling Peter Hankinson that I was going to get the winner in overtime,” Skarda says. “I actually really had a good strong gut feeling that I was going to get one really good chance.”

Little did Hughes and Skarda know at the time that they were on a collision path. Early in overtime, Golden Gophers captain Lance Pitlick skated into the Harvard zone and flicked the puck to Skarda. Low in the right faceoff circle, Skarda saw an opening past freshman Harvard defenseman Brian McCormack and let a wrist shot fly toward Hughes’s near side.

After the game, Woog would succinctly summarize what happened next: “One half-inch, and you’re the champion.”

Skarda’s puck hit the outside of the left post, just above Hughes’s blocker. In the post-championship delirium, Hughes would brashly claim that he knew the shot was not going to get by him.

“I watched the video, and I got beat clean,” Hughes admits. “But I will take it to my grave that I do believe that any other line on that shot, it would’ve been off my blocker, in the corner.”

Skarda, meanwhile, has never lived down being the guy who hit the pipe. He still catches flack from the eight-year-olds he coaches on his daughter’s hockey team in Minnetonka, Minn.

“The girls…call me ‘Piper,’ and I’m sure they’re referring to the Harvard game,” Skarda says.

Moments after the hit post, it would be a Harvard player’s turn to make a career-defining play. Five minutes into the frame, Ciavaglia shoveled the puck to Krayer off a faceoff in the Gopher zone.

Krayer dropped a pass back to freshman defender Brian McCormack, who fired a low, hard shot onto the pads of Stauber. The senior Minnesota goaltender couldnot control the puck, which bounced out into the slot. Krayer pounced on the rebound, skated to his right, and shifted to his backhand.

“I definitely didn’t get full wood on it,” Krayer recalls. “I fanned on it slightly.”

Krayer had a tumultuous Harvard experience, taking the 1987-1988 and 1989-1990 school years off because of academic and personal frustrations. But in that moment, there was nothing but happiness as he watched his shot creep past the right leg of a stumbling Stauber.

“I remember the feeling when the puck crossed the line and the red line went on, and it was instant euphoria,” Krayer says. “I kind of went numb for a couple of seconds as the moment hit me. And once it did, and it occurred to me what that meant, I got buried by a bunch of teammates jumping on me. The rest was sort of just hysteria.”

From the bench, the moment seemed to unravel in slow motion.

“Seeing the puck going in, it’s a bit of one of those surreal moments,” says MacDonald, who would accept the Hobey Baker Award the next day. “You have to check yourself and see if that is really happening.”

“I feel like I’ve seen the highlight in my mind a million times, and I still get excited,” adds Donato, who took tournament Most Outstanding Player honors. “I still get emotional when I see the puck cross that goal line.”

STANDING TOGETHER

While the hundreds of people that gathered at the St. Paul Hotel later that night would remember Cleary’s postgame speech, his words prior to the championship game are not as well documented.

Farden will never forget what Cleary told the Crimson in the Civic Center locker room before the team faced Minnesota.

“I remember him saying something to the effect of, ‘If we win together tonight, we walk together forever,’” Farden says. “I think it was one of the more prophetic statements that anyone made.”

Cleary’s vision was there for all to see earlier this year at the Bright-Landry Hockey Center. The ’89 team had gathered for a reunion at the Harvard men’s hockey team’s Feb. 21 home game against Yale.

Between the first and second periods, the coach and his champions walked onto the ice together for the 25th anniversary recognition ceremony.

At the home bench, Donato seemed to hesitate at first, unsure whether to join his teammates on the ice or his players in the locker room, but his old friends waved him over. Among the men on the rink,not much had changed. Cleary was still laughing. At Cleary’s right hand was MacDonald, who still carried himself with an understated poise.

“It feels like we are on a bus ride to Cornell,” Farden says of team reunions. “Everyone falls back into their old roles. It feels like we are in college again.”

The team stood together, but in the pantheon of Crimson sports, they stood alone. The men’s basketball team would produce Harvard’s next major national athletic headlines in March but finished five wins away from an NCAA title.

Reardon said that the realistic expectations for Harvard athletics—where “anything less than a national championship” is rarely a disappointment—make the 1989 victory all the more special.

“Nobody likes to lose, and the question is, ‘What do you go for?’” Reardon says. “If we set our goals to go after national championships, we’re kidding ourselves, because we’re not set up for that.”

Institutional standards limited Harvard in 1989, and they limit Harvard in 2014. During the reunion, Hughes and his teammates reminisced on the way they won, proud of their accomplishments in Cambridge away from the rink.

“The thing we all pride ourselves on is the fact that we believe we represented what Harvard means both off the ice and on the ice,” Hughes says. “The university took a chance on us, believed in us, and felt that we could thrive as students first and athletes second.”

Since St. Paul, Harvard men’s hockey has retreated from the national stage, last making the tournament in 2006 and last appearing in the Frozen Four in 1994. It may be another 25 years before another Harvard men’s team accepts a national trophy at center ice.

In the meantime, MacDonald hopes the 1989 squad can inspire current and future Harvard student-athletes.

“Winning that national championship sent the message that you can be both a student and an athlete, and you can do it at the highest level,” MacDonald says.

—Staff writer Michael D. Ledecky can be reached at mledecky@college.harvard.edu.Follow him on Twitter @mdledecky.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.