News

When Professors Speak Out, Some Students Stay Quiet. Can Harvard Keep Everyone Talking?

News

Allston Residents, Elected Officials Ask for More Benefits from Harvard’s 10-Year Plan

News

Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin Warns of Federal Data Misuse at IOP Forum

News

Woman Rescued from Freezing Charles River, Transported to Hospital with Serious Injuries

News

Harvard Researchers Develop New Technology to Map Neural Connections

Seeing Old With New: Digital Push Begins in Harvard's Art Museums

Amidst the urbanity of Jamaica Plain, Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum—considered one of the University’s premier science museums—is a plant enthusiast’s haven. From conifers to crabapples, it is home to all manner of flora and fauna, both foreign and indigenous.

Sustaining these plants are many bees—but one in particular is of special interest to researchers. Latched to a wooden track, it is equipped with a UV camera linked to a classroom computer, enabling students to see the Arboretum through the eyes of one of its most important inhabitants.

The Arboretum’s experiment is one of the many examples of how technological innovation has found its way into Harvard’s museum spaces. Supported by the work of metaLAB (at) Harvard, a research center focused on bridging the humanities and technological innovation, Harvard’s museums, both indoor and out, are seeking to create a more digitally-enhanced viewer experience.

“Someone can still look into this meadow and see it’s beauty or its ugliness, but they can be armed with more knowledge,” says Kyle T. Parry, one of the project’s researchers. “There can be this compulsion to look closer.”

As the renovation of the Harvard Art Museums nears its completion this fall, the new space offers many opportunities for including technology.

“The role that digital initiatives will play in this museum will be much more present,” says Director of Harvard Art Museums Thomas W. Lentz. “We hope that people, when they walk in, will go, ‘Yes, this is the museum that I remember, but it’s so much better.’”

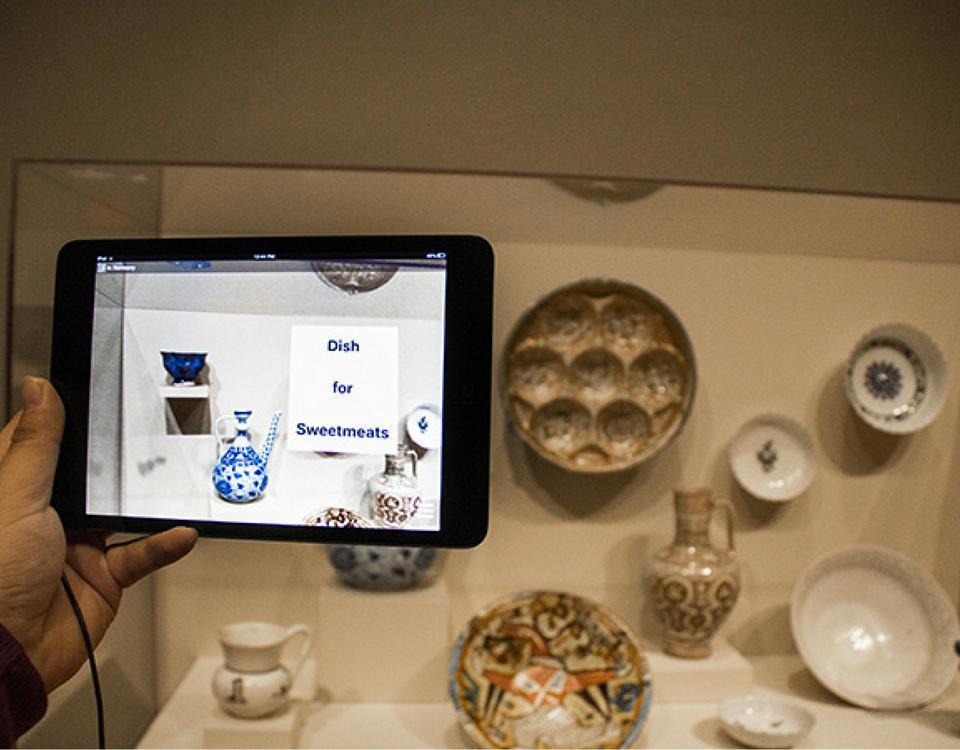

Museum innovators are not waiting until the new building opens to experiment. The opening of the Norma Jean Calderwood Collection of Islamic Art at Harvard’s Arthur M. Sackler Museum in January, for example, marks the first time Harvard Art Museums has used augmented reality technology.

For some, however, a traditional encounter with a work of art in a museum is necessarily devoid of a device like an iPad. And as Harvard’s cultural collections come of age in the digital era, curators and other museum administrators must straddle a fine line between enhancing their collections and distracting from their original purpose.

FOGG 2.0

With its main building under renovation, Harvard Art Museums is undergoing a makeover. The building—an empty giant on Quincy Street—is more pregnant with possibility than ever before.

The completion of the renovation, which was first conceived almost ten years ago and broke ground in 2010, has been delayed by almost a year due to structural problems and unexpectedly high levels of asbestos. But by the time the building is set to open in late 2014, Lentz says the museum should be “state-of-the-art.”

“This isn’t going to be simply a very expensive, static treasure house,” Lentz says. “We fully expect this museum to much more effectively and imaginatively serve all of Harvard.”

According to Lentz, the existing structure of the building is easily adaptable to new technological additions. Although museum administrators stressed that all plans for the new space are preliminary, there are many ideas for how to bring the galleries into the digital age.

One project currently under consideration, for example, is a digital “screen-wall” on which visitors to the museum could use gesture-based navigation—harnessing body movements rather than touch to trigger the screen—to explore digital resources, according to Jessica L. Martinez ’95, Director of Academic and Public Programs.

Additionally, the new museum will feature three 1000-square foot “curricular galleries” to be used for teaching. By coupling exhibit and classroom space, the museum will become a tool for classes that may be better suited to an object-based syllabus than a text-based one.

In light of the new emphasis on interactive pedagogy, museum administrators are interested in a metaLAB project called “Teaching with Things,” which aims to develop a virtual representation of an artifact’s shape and size in order to facilitate annotation, says metaLAB creative technologist Cristoforo Magliozzi.

“[The technology] is becoming a lot cheaper, a lot leaner, and a lot more mobile,” Magliozzi says. “More and more museums and institutions of that sort are having these capabilities in-house.”

Magliozzi also highlighted the potential value of digitizing content that is in storage, since the Harvard Art Museums will only be able to exhibit “the tip of the iceberg” of its full collections when it opens.

“Index,” Harvard Art Museums’ magazine, is looking forward to a digital transition as well. Originally a print magazine, the publication will eventually become entirely digital.

“We’re tinkering and experimenting and rolling it out in all these different venues,” Steward says. “We’re making connections between what you can do in the gallery and what you can do at home.”

ENGAGEMENT ANEW

What the Harvard Art Museums hopes to do is already underway in Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum. Curators have equipped the 250-acre garden with technology aimed at bringing the plants to life digitally. As a result, the Arboretum has served as a laboratory for the kind of technology the metaLAB is looking to introduce in Harvard’s artistic collections, and a blueprint for what a digitally-equipped art museum could look like in the future.

Working with Nuvu Cambridge—an innovation center attended by high school students who take a semester off to collaborate on projects with experts from MIT and Harvard—the metaLAB designed a series of digital modules for the Arboretum.

In one module, for example, students built a robotic flower that simulated conditions at the Arboretum by opening, closing, or changing color. Another module tasked them with building a birdhouse with several hidden sensors. Using a single-pixel camera, the birdhouse was able to measure the light hitting the tree, which in turn fed into a visualization of how a tree perceives light.

The purpose of the new modules is to gather and display “metadata”—the cloud of information surrounding each artifact. It is data about data, according to Yanni A. Loukissas, metaLAB senior researcher, and it could represent an exciting new path for museums.

“Our sense throughout this whole project has been that, if you do it right, you can create this interesting ecology of experience... from encounters with the raw physicality of the collection to encounters with the metadata of the collection,” says Parry, the metaLAB researcher experimenting with digital videography at the Arboretum.

For museums, the potential to unlock supplementary digital information about an object could help visitors understand artifacts in new ways. “People are used to having navigation and search at their fingertips,” Loukissas says. “I think the museum... kind of begs for that.”

For example, the ability to digitally view three-dimensional objects from all possible angles could help museum-goers overcome the physical constraints of galleries. Even seeing a video of someone handling an object, according to Loukissas, psychologically enhances understanding of three-dimensionality.

Annotating objects digitally is another method of producing metadata. For example, Houghton Library houses artifacts called “ostraca,” pottery fragments that were used in ancient Athens to vote in banishment trials. Loukissas and other innovators think that a researcher examining the shards should be able to reference informational material about the object through digital annotations.

“We’re in a new means of engagement,” he says.

HERE TO STAY

For developers at the metaLAB, this integration of technology across disciplines is the next step in unlocking the latent possibilities of a collection. But as developers brainstorm how to integrate cutting-edge technologies into the museum experience, they are meeting resistance from those hesitant to move away from the traditional museum encounter.

Harvard Art Museums administrators, however, suggest that they do not see technology as a threat. They are careful to emphasize that their first priority is what Martinez calls “deep and prolonged looking.”

“We have a deep, strong, almost religious feeling that nothing replaces the objects in the museum,” Lentz says.

In Jamaica Plain, Parry has already encountered resistance from the public regarding technology in the Arboretum. Some people, he says, are worried that the presence of devices like iPads will steal the spotlight from the plants themselves.

“A lot of people, when we talk about this project, are concerned that we’re taking a site that offers you something other than the urban experience and muddying it,” he says.

This kind of worry is not exclusive to a natural museum like the Arboretum. In discussions with art museum administrators, Loukissas says that he and other developers have spent a lot of time considering how people can “divide their attention between the material artifacts that have historically been the focus of attention and the clouds of metadata that have encircled them.”

According to Parry, one possible solution is the incorporation of sound into galleries. Listening—rather than reading or watching extra material—while viewing exhibits could increase immersion while minimizing distraction. Although audio tours have been a common fixture in the museum scene for years, curators at Harvard are thinking beyond the traditional format.

At an exhibition in the Sackler Museum called “Jasper Johns / In Press: The Crosshatch Works and the Logic of Print,” curators used a device called a “sound dome,” a reverse cone-of-silence that projects sound downward so that only the person standing below it can hear the audio.

And at the Arboretum, researchers are working with soundscape artist Teri Rueb to produce an oral history accompanying a path through the Bussey Brook Meadow, a wetland section of the Arboretum.

“The technology is here to stay, and we have to deal with it,” Loukissas says. “That’s not to say that we should accept the current manifestations of the technology. One thing we know for certain is that these types of interfaces will change and we have the chance to shape them.”

—Staff writer Gina K. Hackett can be reached at ghackett@college.harvard.edu.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

CORRECTION: May 14, 2013

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that a camera with a UV lens at Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum is robotic. In fact, it is latched to a wooden track.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.