News

When Professors Speak Out, Some Students Stay Quiet. Can Harvard Keep Everyone Talking?

News

Allston Residents, Elected Officials Ask for More Benefits from Harvard’s 10-Year Plan

News

Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin Warns of Federal Data Misuse at IOP Forum

News

Woman Rescued from Freezing Charles River, Transported to Hospital with Serious Injuries

News

Harvard Researchers Develop New Technology to Map Neural Connections

Speaking with Shadow

Artist William Kentridge advocates for irrational thought in artistic practice.

In the first installment of this year’s Norton lecture series, South-African artist William Kentridge described the experience of an 8 year-old standing on a beach watching his shadow lengthen. “The shadows are a version of you,” said Kentridge to his audience in Sanders Theater. “You lift your arm, and the shadow lifts its arm. You step forward, and the shadow steps forward...I am its controller, but also delighted and amazed at the speed and dexterity I didn’t know I had. It’s an extension of me, and it’s more than an extension of me.”

Kentridge’s description of the child and its shadow in the lecture, which is titled, “Drawing Lesson One: In Praise of Shadows,” illustrates the complexity with which each individual inhabits his or her visual surroundings. It also serves as a point of departure for Kentridge’s larger project: to identify the strategies and discoveries of visual artists as a valuable form of knowledge that is applicable outside the sphere of art practice and art history. “It is in the very limitations and leanness of shadows that we learn,” Kentridge remarked. “We complete the illusion and, recognizing ourselves completing it, become aware of that activity.”

The artist’s choice to term his lectures “Drawing Lessons” serves to assert the primacy of non-linear, image-based thinking, both within his practice and the lectures themselves. “They’re called drawing lessons because they’re not drawing lessons,” Kentridge said in an interview. “They’re talking about all the ideas which are there before drawing happens.... They’re also called drawing lessons to state that I’m speaking as an artist, not as scholar.”

Kentridge’s desire to approach the scholarly feat of the Norton Lectures as an artist is in many ways not only the goal, but also the subject of each lecture. While he articulates his studio practice in terms that are broadly accessible, his primary concern is not to demystify artistic process, but instead to argue in support of its ambiguities.

CREATIVE CAUCUS

Kentridge is the 2011-2012 recipient of the Charles Eliot Norton Professorship of Poetry, an annual lectureship designed to honor innovation across artistic disciplines. C.C. Stillman, who endowed the chair in 1926, stipulated that, “in the administration of this gift, the term Poetry shall be interpreted in the broadest sense, including together with Verse, all poetic expression in Language, Music, or the Fine Arts.” In agreement with Stillman’s request, the task of nominating candidates cycles through Harvard’s departments, with committee members drawn from the music, art, and literature faculties in alternate years. This year’s selection panel consisted primarily of professors in the History of Art and Architecture and Visual & Environmental Studies departments.

Homi K. Bhabha, Anne F. Rothberg professor of the Humanities, Director of the Mahindra Humanities Center, and a member of this year’s selection committee, says that the assembled members looked for candidates engaged in either art scholarship or art practice before considering those who bridged the two fields. “We looked at a category of practicing artists who were also interested in the history of art...artists who had careers as writers and thinkers, placing their artwork within more general intellectual problems,” Bhaba says. “And very quickly, William Kentridge came to the top.”

Maria Gough, Joseph Pulitzer professor of Modern Art and also a selection committee member, pointed to the rare combination of attributes and interests that the committee sought in its candidates. “Of the many reasons why the committee invited Kentridge, one of the most important is that he is an artist with a tremendous facility for communicating with a wide range of people in the Harvard community and beyond it,” Gough says. “[Kentridge’s] work is involved with the traditional medium of drawing, but always in tandem with moving image media and performance; it is also involved with fundamental problems like the history of colonialism, and it seriously engages with the history of art.”

While the broad political and intellectual scope of Kentridge’s art may initially have brought him to the committee’s attention, both Bhabha and Gough emphasize that wide-ranging appeal was a secondary consideration to the quality of the artist’s work. “We are thinking about somebody who responds to the world in his or her work,” Bhabha says. “The primary condition is really the interest of the work itself.”

MOVING PICTURES

Kentridge’s creative output spans a variety of media including drawing, animation, film, set-design, installation and performance. Yet, he terms his lectures “Drawing Lessons.”

“[Kentridge] is using the concept of drawing in an expanded sense. By the late 20th century, the very notion of drawing had been expanded almost beyond recognition,” says Gough. His past Norton lectures have made great use of his paper work; the first work discussed was “Shadow Procession,” a stop-motion animation of cut-paper silhouettes. In the second lecture, entitled “A Brief History of Colonialism,” Kentridge introduced a variety of paper maquettes—small-scale models—and puppet theaters constructed in connection with the production he directed of Mozart’s “The Magic Flute.”

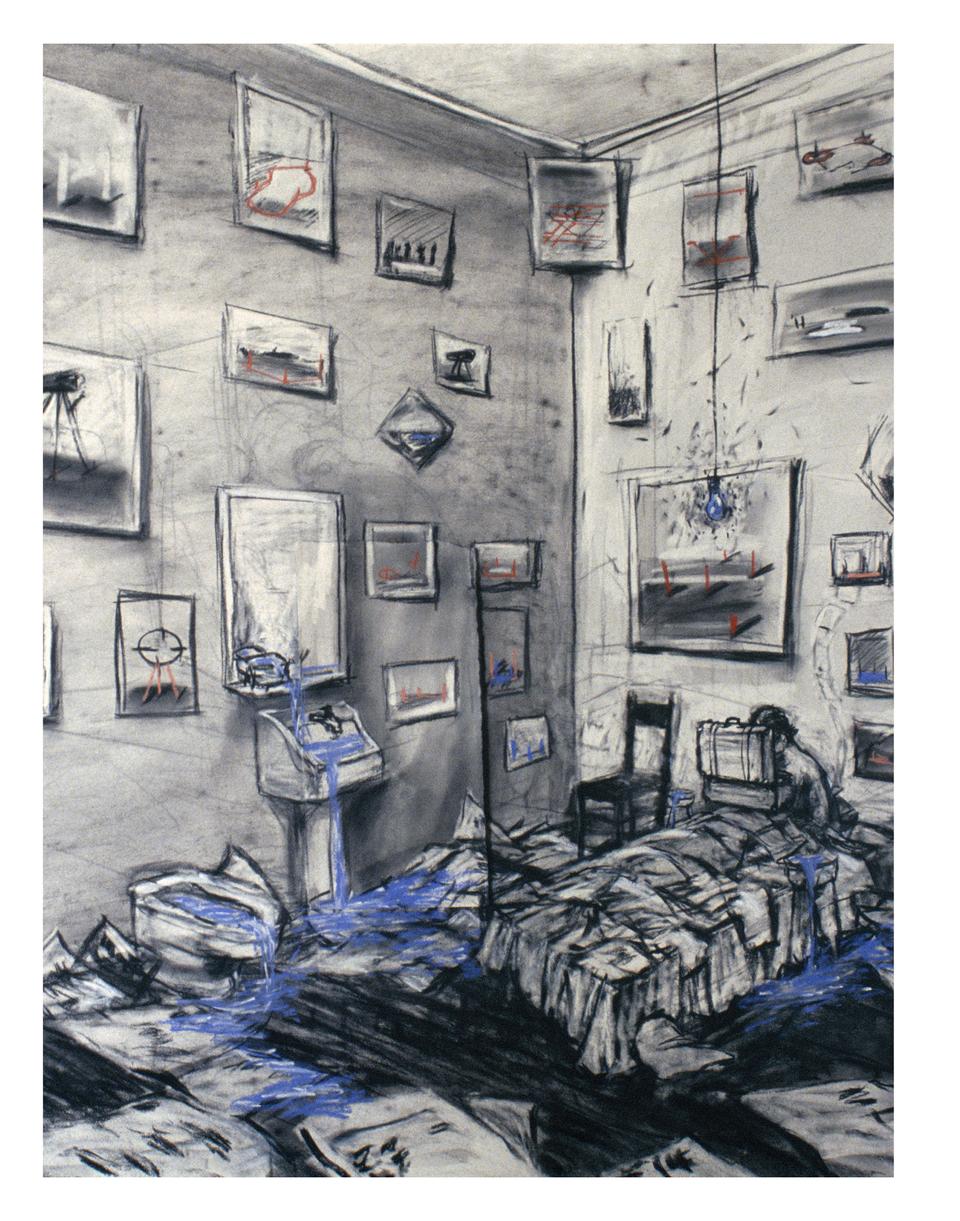

In the third “Drawing Lesson,” entitled “Vertical Thinking: Johannesburg Biography,” Kentridge will introduce the work for which he is arguably best known, which he refers as “Drawings for Projection.” These works were created using his signature variation on stop-motion technique, which involves repeatedly altering and rephotographing a charcoal drawing so that the images, when sequenced, create the illusion of motion and time passing. In “9 Drawings for Projection,” a series of short films completed in 2003, Kentridge examines post-apartheid Johannesberg through the lens of three characters: Soho Eckstein, the merciless industrialist, Mrs. Eckstein, his neglected wife, and Felix Teitlebaum, the romantic soul who becomes Mrs. Eckstein’s lover. These haunting, meticulously crafted narratives garnered Kentridge international acclaim for his innovative use of erasure as animation.

Kentridge’s decision to locate his work in between the genres of drawing and film has provoked its share of critical confusion. In her article “The Rock: William Kentridge’s Drawings for Projection,” art historian Rosalind E. Krauss explains that Kentridge sees his filmic process as a “derivative of drawing,” which for him necessitates that the animations be displayed alongside their constitutive drawings in museums and galleries, as opposed to conventional theaters. Krauss writes that this mode of presentation “has annoyed certain commentators who...otherwise admiring Kentridge’s work, don’t see why he shouldn’t just show them as animation films, entering them into the space of cinema.”\

Other viewers do not recognize any further need to articulate Kentridge’s unique method of production. “It may be helpful to ask in certain contexts, you know, what are you really? But in the moment of making something that seems like the least important question,” says Peter L. Galison, Joseph Pellegrino University professor and Kentridge’s long-term collaborator. “I think sometimes work functions in several registers, and that’s not something to apologize for, but something to aspire to.”Kentridge, maintaining that “the work must make it’s own way in the world,” does not consider the classification of his art to be of pressing importance. However, he suggests that the process of generating his charcoal-based animations more closely resembles drawing than filmmaking. “The strategies of making the work are the strategies of making a drawing more than they are the traditional strategies of making a film,” Kentridge said in an interview. “Film has always been a large social undertaking with a studio and many people involved, and the animated films are an attempt to make a film which you can make on your own time, with indecision, with uncertainty.”

LASTING TRACES

The uncertainty and indecision Kentridge describes may reflect the difficulty of representing his films’ grim subject-matter: the aftermath of apartheid, which he likens to an “immovable rock.” “The scale and weight with which this rock presents itself is inimical to that task [of representation,]” Kentridge wrote in 1990 of the apartheid. Despite the formidable task of depicting these atrocities, he maintains that the artist’s studio can serve as a retreat in which to represent and work through the memory of the past.

In his second lecture, Kentridge suggested a link between the challenge of representing tragedy and his concept of the universal archive. He proposed that the lingering images of every event to have occurred on earth are preserved and projected into space in the form of photons moving at the speed of light. Though the photons travel further away from earth, these images of human history may still be visible to a well-positioned observer. “The universe is a collection of images.... We are transmitting stations broadcasting ourselves the whole time,” Kentridge said. “Once launched, the image cannot be called back.”

The concept of projected images that are not fleeting but lingering in three-dimensional space relates to the technique behind Kentridge’s drawings for projection. The material build-up resulting from the artist’s repeated alteration and erasure of charcoal marks parallels the accumulation of events in the universal archive. Without explicitly engaging the specific political figures and events of post-apartheid South Africa, Kentridge’s suggestive layering of marks reflects the ever-present memory of “the rock,” even as it resists direct representation.

“NECESSARY STUPIDITY”

Kentridge has several times punctuated his lectures with variations on the phrase, “And now, we must return to the studio.” For Kentridge, the studio is the site of what he describes as a “full frontal assault” of multiple processes and ideas in which an artist may be engaged simultaneously. The non-verbal discoveries resulting from this multiform engagement can be difficult to translate from the workspace to the lecture hall. To illustrate this conflict, Kentridge projected four identically dressed images of himself which—as the real Kentridge paused in his delivery—continued to pace forward and backward on the screen overhead, reciting various thoughts and phrases from lecture notes to create an unintelligible, overlapping chorus.

According to Kentridge, an artist’s ability to operate on multiple fronts at once depends on his or her cultivation of ”necessary stupidity.” “The necessary stupidity refers to the activities which you can’t really explain in a rational way,” Kentridge said in an interview. “As soon as you start to explain them rationally, they are extremely foolish and don’t have a logical sense, but nonetheless are extremely important.” Though Kentridge does not elaborate on the exact nature of these activities, he associates them with an abandonment of linear thinking for an emphasis on observation and material exploration.

Kentridge’s commitment to asserting the primacy of this concept in the Norton lectures to an audience awaiting the display of brilliance is one of the drawing lessons’ greatest points of tension and interest. His promotion of this concept subtly critiques the privileged status of the more traditional, scholarly forms of knowledge in which much of Harvard’s community is engaged.

“His argument is that artistic practice is a form of knowledge production...and shouldn’t be viewed simply as a form of supplement or afterthought that takes place once the important work of, say, philosophy, or some other discipline has been done,” Gough says. “This was not a lecture solely for the art world or the art-history crowd....This was a lecture for a university with a complicated but potentially dynamic relationship to the advanced forms of experimental aesthetic practice.”

Bhabha suggests that though Kentridge may be critiquing the limitations of the lecture format, he works within it to present images on their own terms. “I would argue it was not only about art as knowledge production, but knowledge as art production at the same time,” Bhabha says of Kentridge’s first lecture. “He changed the lecture format because the visual materials he showed were not simply illustrations of something he had said. They had their own narrative which converged with the lecture.”

Kentridge suggests that privileging images over text naturally occurs in the delivery of an artist talk, but that it also reflects his conviction in the primacy of visual knowledge. “Argument and logic [are] something on top of the world, hovering over it, but not a part of it,” said Kentridge in his first lecture, describing his disillusionment early in life and the reason for turning to the “limitations and leanness of shadows” as legitimate sources of knowledge.

“If you’re artist and not a scholar then obviously your life has been not about words, but about images,” Kentridge said in an interview. “So to defend that activity of making meaning through practical activity, which is what artists do, is to show that there can’t always be a privilege of rational, word based thinking.”

—Staff Writer Sally K. Scopa can be reached at sscopa@college.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.