News

HMS Is Facing a Deficit. Under Trump, Some Fear It May Get Worse.

News

Cambridge Police Respond to Three Armed Robberies Over Holiday Weekend

News

What’s Next for Harvard’s Legacy of Slavery Initiative?

News

MassDOT Adds Unpopular Train Layover to Allston I-90 Project in Sudden Reversal

News

Denied Winter Campus Housing, International Students Scramble to Find Alternative Options

GSAS Students Face Tough Job Market

When he graduates from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Guy P. Smoot hopes to become a professor.

A student in the comparative literature department, Smoot said he has found working with students rewarding as a teaching fellow at the College, particularly getting them excited about the material he teaches.

“I like to have an impact on the way people view the world,” Smoot said.

Smoot’s career aspiration is a common one among graduates of GSAS.

According to Garth O. McCavana, GSAS dean for Student Affairs, about 70 percent of the school’s 4,000 students go into academia each year, either by jumping directly into the professorial job market or by pursuing postdoctoral studies.

The goal for many graduate students is to eventually earn tenure, the guarantee of lifelong employment awarded by universities to their most valuable faculty members.

Most students spend anywhere from four to seven years pursuing their doctoral degrees and many wonder whether there are teaching jobs open for them once they graduate.

“The job market is not great at the moment,” McCavana said. “Our students are doing well, but it doesn’t mean everyone is landing their dream job.”

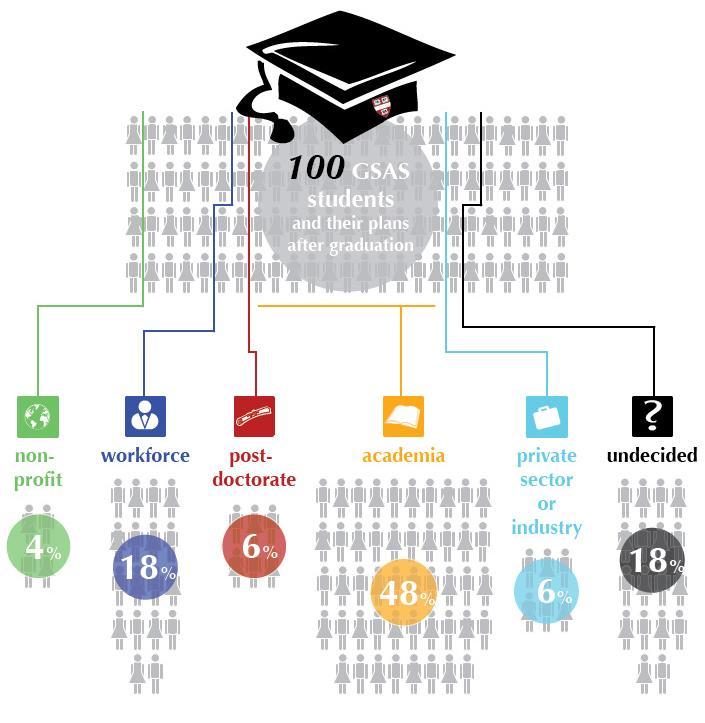

Of the 100 GSAS students interviewed by The Crimson, 48 said they hoped to pursue jobs in academia upon graduation.

For doctoral candidates in the humanities graduating from Harvard, the path to professorship is especially long, rocky, and uncertain—qualities that have only been worsened by the current economic climate.

INGREDIENTS FOR SUCCESS

The path to a tenure-track position is similar across most fields of academia.

A candidate’s published academic writings are key to the application process, as they serves as indicators of how the student will fare as a full-time scholar.

“Your publication record shows that you can finish things and get research done,” assistant professor of chemistry and chemical biology Emily P. Balskus said. “It’s more the quality than the quantity, and [if] you really made a contribution to the research.”

Most departments require their graduate students to serve as teaching fellows even as they work on their dissertations.

“There’s a dilemma among many graduate students who are done with their course work,” said Smoot. “You pass your general exams, and then you have to teach while you work on your dissertation.”

For graduate students, the daunting process of hunting for jobs usually begins in the fall of their final year at Harvard.

Most academic disciplines utilize centralized fora that list all of the openings in that field from departments and universities across the globe.

Applicants for each position are whittled down and a small minority of candidates receive invitations to interview with faculty. Eventually three or four candidates are brought to campus for on-site visits, during which they go through what McCavana described as an “intensive interview process.”

“People are literally on from 8 a.m. to when dinner is over—it’s all part of the interview,” McCavana said. “They want to see how you get along with the colleagues.”

Balskus, who interviews candidates applying to Harvard’s chemistry department, said the process is “very fair.”

“From my perspective, what you are asked to do is in many ways very reflective of the things you’ll do as an assistant professor,” Balskus said. “You’ll have to talk and explain your work, and you’ll have to interact.”

HARD TIMES FOR HUMANITIES

The number of job openings in humanities departments has declined as cash-strapped universities divert resources to the sciences.

“Universities are putting more money into sciences than humanities,” said English professor Amanda Claybaugh. “[Universities are] hiring in the sciences rather than the humanities.”

Furthermore, she said, universities are “under incredible financial constraints.” As a result, the hiring of tenure-track professors has slowed as schools appoint more and more adjunct professors—lower-paid professors not on the tenure track, whose primary duty is to teach students.

As a result, graduate students face even greater uncertainty while wrapping up their dissertations and beginning their hunt for a job.

And with fewer non-academic jobs available overall, those who graduate with Ph.Ds in the humanities face unsure employment prospects.

“Everyone feels concerned about whether they can get a job they want, and second, whether they can get a job at all,” said L. Julie Jiang, a postdoctoral fellow in the linguistics department.

Claybaugh said that she often cautions College students against attending graduate school.

“It’s a very risky thing to do a Ph.D these days,” said Claybaugh.

THE HUMANITIES POSTDOC

The realities of the job market have made postdoctoral research an often appealing option for unemployed graduate students.

Smoot, who is in his fifth year of graduate studies, said he will apply for a job as a professor, but if he does not succeed his backup plan is to remain in academia as a “postdoc.”

Smoot’s story is one echoed by many graduate students looking to grow their credentials before applying to jobs.

“[Postdoctoral research] allows them to build up their credentials to go on to the academic job market, because it’s become more and more difficult,” said McCavana. McCavana said he has noticed a recent rise in the number of humanities postdocs.

László Sándor, a Ph.D candidate in the economics department, said he thinks the option of pursuing a postdoc became more attractive to graduate students in the humanities following the fallout from the economic crisis.

He described the postdoc market as one that emerged for students who wanted “to wait” and spend more time at a university before entering the job market.

But despite the fact that it is often long and uncertain, the path towards academia is one that Harvard graduate students continue to pursue.

“Our department does really well,” Claybaugh said of Harvard graduate students in the English department applying to be professors. “Our students are cautiously optimistic and they have good reason to be.”

For Jiang, the discussion about the difficult job market overlooks an important factor, one that continues to motivate graduate students to apply year after year.

“You really have to have the passion and enthusiasm and love for the thing you do,” Jiang said. “Without these things, I don’t think people will be able to stand the difficulties they face on the path to academia.”

—Staff writer Laya Anasu can be reached at layaanasu@college.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.