News

When Professors Speak Out, Some Students Stay Quiet. Can Harvard Keep Everyone Talking?

News

Allston Residents, Elected Officials Ask for More Benefits from Harvard’s 10-Year Plan

News

Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin Warns of Federal Data Misuse at IOP Forum

News

Woman Rescued from Freezing Charles River, Transported to Hospital with Serious Injuries

News

Harvard Researchers Develop New Technology to Map Neural Connections

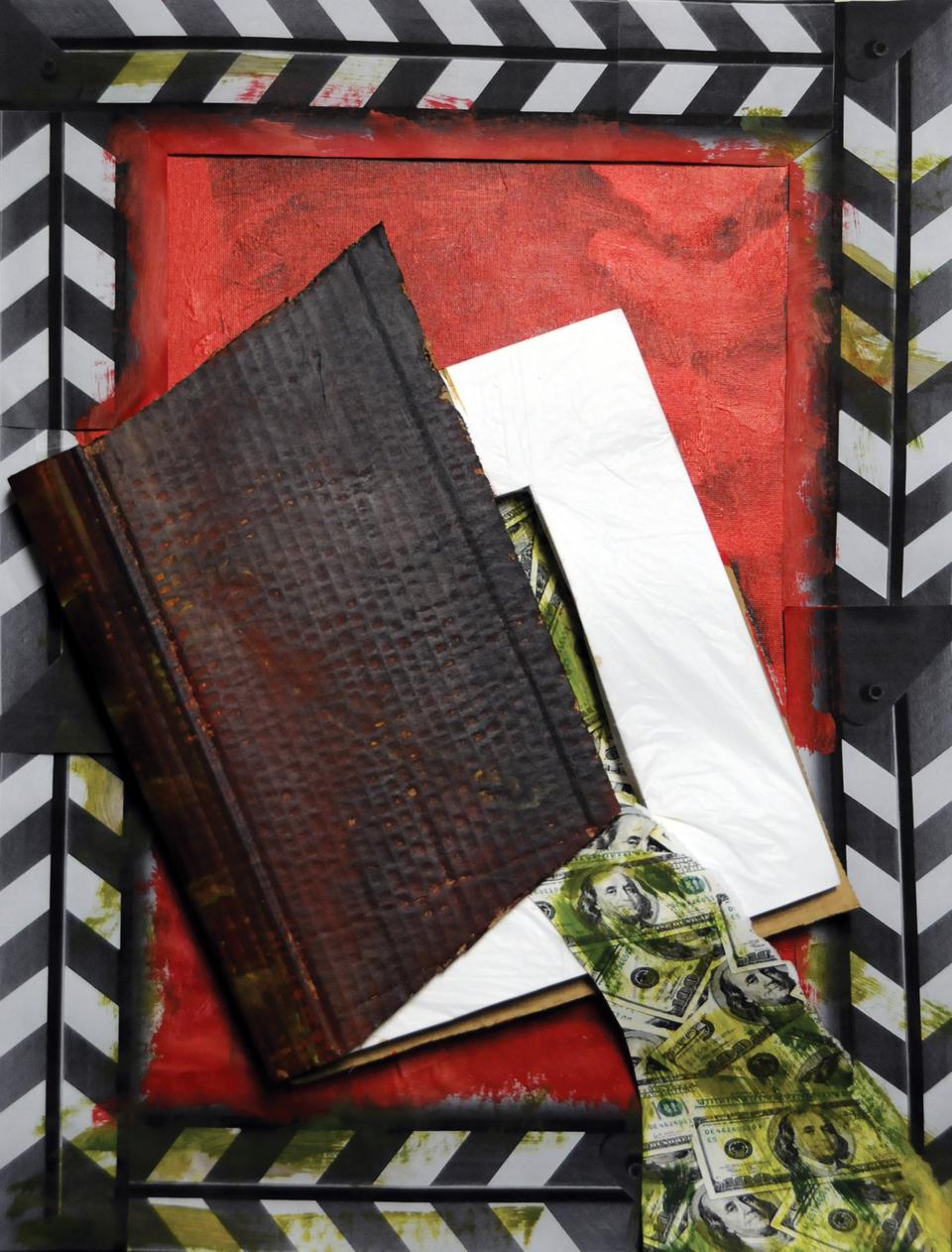

Secondhand Showings

The Great Recession causes Hollywood studios to limit the artistic possibilities for big budget movies

A confident and dangerous Sean Parker hovers over Mark Zuckerberg and Eduardo Saverin in “The Social Network.” “You don’t even know what the thing is yet,” he says. “How big it can get, how far it can go. This is no time to take your chips down. A million dollars isn’t cool. You know what’s cool?” The scene jumps back to the deposition and Saverin exclaims: “A billion dollars. And that’s what shut everybody up.”

This drive to financial success and fame that leads Zuckerberg into moral ambiguity also directs the motivations of Hollywood filmmakers. Perhaps more insidiously, the prospect of great profit encourages a stifling of filmic innovation just as it silences the legitimate ethical concerns of Saverin.

Indeed, as the economy worsens, Hollywood film studios increasingly hedge their bets. This risk-aversion has caused studios to focus on three kinds of narratives: those based on real life events, previously successful franchise films, and fictional stories already popular in our collective cultural consciousness. The high costs of production for major motion pictures have always limited creative possibility in popular cinema, but this constriction of artistic possibility may be at its most severe today.

CASH AND CALIBER

A screenplay can make its way to the screen via multiple institutional paths, but most major studio films are produced with the same goals as any other financial investment. A production company and a distribution company gather the necessary capital in order to make the film with the expectation that they will at least break even. Breaking even is worthwhile in order to establish a relationship with a specific actor or director, or in an attempt to garner prestige by winning awards. Far more often, however, the decision to produce a film is profit-based. The prioritization of commercial success is so great that a distribution company generally spends an equal amount of money producing a movie and advertising it. For major studio releases, thousands of prints are generated and shipped to theaters across the country at an unimaginably high fixed costs that create intense pressure for success.

“Movie producers want to invest in something that they know is going to be profitable, and they can tell how these movies are going to do at the box office based on how the public has already received these stories,” says Daniel J. Rubin, a screenwriting lecturer in the English Department who co-wrote the popular movie “Groundhog Day.” “The less money there is floating around in Hollywood, the more this impulse takes hold.” Only when Hollywood has a lot of money, then, can it afford to lose some.

This phenomenon has clearly been evident this year. Of the 10 movies nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture, seven are either based on non-fiction accounts, remakes of previously successful stories, or new installments in franchise films. Of the five films nominated for Best Director, four fall into one of these three categories. “The King’s Speech,” a retelling of events surrounding World War II, won both awards. In other artistic media, success of this nature would be unlikely; no painting or sculpture, for example, would win such significant critical acclaim without a conceptually original premise.

The practice of adapting non-fiction events into film, however, dates to the very beginning of the film industry and became especially popular in the 1920s and 1930s. According to Associate Professor Art Simon of Montclair State University, “[During this period] producers at Warner Brothers would actually comb the newspapers regularly looking for events to adapt to the screen.” Of course, expectations for film during this period were entirely different. In an era before television, the only medium people could use to have the news to play out directly in front of them was film.

As Visual and Environmental Studies (VES) Professor Alfred Guzzetti explains, “Fewer movies are being produced now, and fewer movies are being released ... the cost of creating and releasing a movie has really, really gone up even in absolute dollars. It’s a much riskier enterprise.” When a studio produces many low-budget movies annually, it can afford to absorb the losses of a flop, but when a studio is producing few high-budget movies, the studio cannot afford these costs. This trend could potentially prove permanent as low-cost new media formats compete with films for the attention of audiences.

'THE CHILD’S PART'

Considering most moviegoers can intuit how film narratives will resolve themselves, it may not be intrigue that draws them to the theater; it may rather be the dependability provided by a narrow set of possible storylines. There is an important difference between stories with predictable outcomes and those with popularly known outcomes. In the case of “Black Swan,” an audience member can fairly accurately predict the outcome from the composition of characters, but there is still an element of suspense. However, in “The King’s Speech” the ending is already known by every audience member before he or she ever sees the film—Britain will win World War II and King George VI will find a way around his stutter.

“Films are projected in order not to require too much interpretive labor or comparative study of variation in the manner of myth and folklore,” VES Professor Tom Conley wrote via email. “Something of the child’s part is in these films for the reason [that] enjoyment comes from repetition: as children we want to hear stories over and again, no matter how their narrative might turn out.” Works of art are generally praised for originality, which by its very nature challenges the viewer. Moviegoers, instead, seem to value something else in film: the tranquility of seeing expected, logical resolutions play out in the world before you, as they so rarely do in real life.

This brand of predictability extends beyond plot arc. “Many moviegoers didn’t see ‘True Grit’ because they remember the 1969 John Wayne version,” Simon says. “Instead, many people went to see the movie because they were fans of the Coen brothers and it was merely a case of personalities.”

AUDIENCE ATTRACTION

As such, film producers do not always assume that a film’s financial success will be based on the popular attention surrounding real-life events or the success of a prior version of the same story. They also look toward projects involving celebrity directors or actors who have previously churned out large sums of money. Even in the recession, producers have been willing to bankroll movies such as “Black Swan”—directed by Darren S. Aronofsky ’91 and starring Natalie Portman ’03—and “Inception”—directed by Christopher Nolan and starring Leonardo DiCaprio—because of the trust they have in the ability of these actors and directors to attract audiences to the theater.

Depending on personalities, however, has not proven to be a surefire formula for movie producers. Guzzetti specifically cites the example of director Michael Cimino, whose 1978 film “The Deer Hunter” earned millions of dollars at the box office and five Academy Awards. This showing motivated producers at United Artists in 1980 to offer Cimino what Guzzetti described as a “carte blanche” to direct “Heaven’s Gate.” The movie was a critical and commercial flop of historic proportions, and it helped to bankrupt United Artists. “Many people look at that and think: how can we keep that from happening?” Guzzetti says. “Deal with known quantities—buy a book, deal with a director who has always made money like James Cameron, have something that’s more predictable.”

Cimino’s failure, then, demonstrates that celebrity culture is a fickle assurance in attaining financial success. The most reliable formula for making a profit in the film industry may lie in retelling a popular tale.

CINEMA OF THE SPECTACLE

Unlike conventional material products, a film’s performance is dependent on its critical reception and marketing figures such as its initial box office sales. Most commercial products, such as cigarettes, are not highly dependent on these factors. For a given brand of cigarettes, financial success isn’t determined by sales during its first week of distribution or reviews in popular literature. A film’s success, on the other hand, is subject to these external factors. “It’s like a sport,” Guzzetti says. “People root for movies. Audience members not only follow whether a movie is good, but how the movie is doing. People identify with the business end of movies ... in a way they never did in classical Hollywood.”

In other words, the film industry represents much more to culture than the sum of the products that it produces—it is a spectacle in which fans become personally attached to the commercial and critical reception of particular shows. This is why the Academy Awards is regularly one of the most widely watched annual television events: people not only enjoy watching the content of a movie, but the commercial route that the movie itself takes from the beginning of development to the end of distribution. The possibilities for profit in a well-liked movie are therefore magnified by a surrounding consumer culture that increases the gap between success and failure. The risk for a flop becomes untenable.

BRAND ABILITY

Documentaries might seem immune to the hackneyed plotlines and characters that constitute so many popular movies—in order for a documentary to exist, it must be making an original argument. The pressures of Hollywood, however, have infected the genre with many of the symptoms of the economic squeeze that have plagued studio films. This change proves the extent to which the Hollywood studio system is limiting the creative and argumentative possibilities of major films in wholly new ways. Simon believes there has been an increase of so-called “branded” documentaries. “After filmmakers such as Michael Moore demonstrated that they could draw crowds to the box office,” Simon says, “movie producers began to think about the profitability of documentary films and began to finance large projects such as ‘Fahrenheit 9/11’ and ‘An Inconvenient Truth.’”

These large budgets have allowed documentaries to experiment with filmmaking techniques previously reserved for Hollywood studio films, including polished visuals, special effects, and original soundtracks, all of which make widely-distributed documentary films in line technically with studio pictures. This trend has been especially apparent in documentaries of the last year such as “Inside Job” and “Waiting for ‘Superman,’” which have used enormous budgets by documentary standards in order to create a Hollywood feel.

This overdone approach to documentary filmmaking has increasingly taken what used to be an observational account of event and increasingly inserted the voice of the director. Celebrity culture within documentary filmmaking may allow people to come to anticipate the content of a documentary in advance, just as Conley suggested they do with studio pictures. “You know what you’re going to find in a Michael Moore documentary before you even get there,” Simon says. “In fact, the reason you’re probably even going is because you agree with his political viewpoints.” In the modern economic reality of popular cinema, the standard issue has a growing dominance.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.