News

When Professors Speak Out, Some Students Stay Quiet. Can Harvard Keep Everyone Talking?

News

Allston Residents, Elected Officials Ask for More Benefits from Harvard’s 10-Year Plan

News

Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin Warns of Federal Data Misuse at IOP Forum

News

Woman Rescued from Freezing Charles River, Transported to Hospital with Serious Injuries

News

Harvard Researchers Develop New Technology to Map Neural Connections

Despite Lofty Ambitions, 'Storyteller' Mystifies

'The Storyteller of Marrakesh' by Joydeep Roy-Bhattacharya (W.W. Norton & Company)

“First, always remember that either a story carries love and mystery, or it carries nothing,” advises the narrator’s father in Joydeep Roy-Battacharya’s new novel, “The Storyteller of Marrakesh,” as the narrator Hassan prepares to take his father’s job as a traditional storyteller. “Second,” he continues, “outside of the broad themes determined by the story sticks, the trick is to make up everything out of a whole cloth. Third, a story must not have a clean resolution. That way you will keep your audience coming back for more.” Early in the book, it seems that Roy-Bhattacharya lays out his rules for storytelling within the story itself.

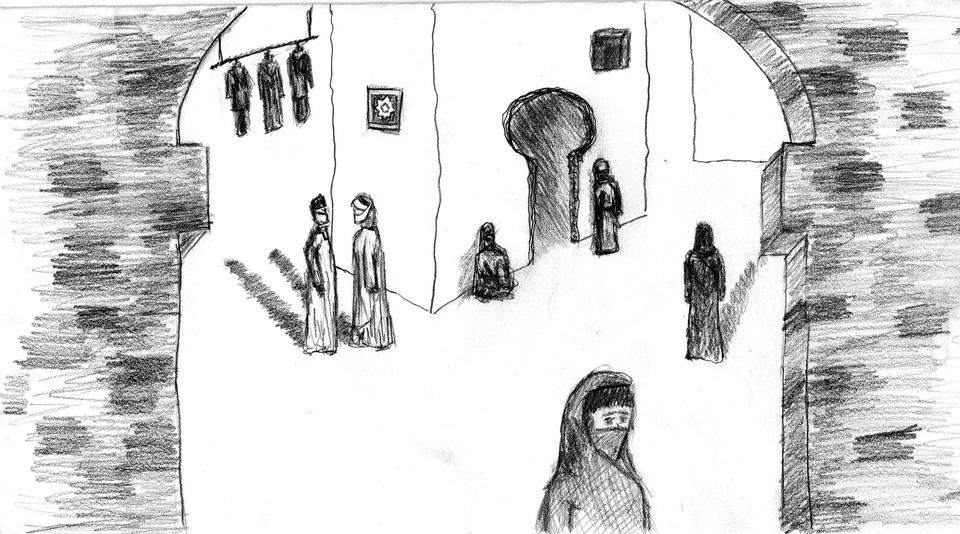

In “The Storyteller of Marrakesh,” the first in a series set in the Islamic world, Roy-Bhattacharya explores the art and craft of storytelling by weaving together a multitude of voices and perspectives. Each character’s story offers clues to unravel the disappearance of a foreign couple in the Jemaa al Fna, located in the old quarter of Marrakesh—one of the busiest marketplaces in Africa and the world. The novel seduces with taut mystery and luscious immersion into the hubbub of the marketplace and its heritage of Islamic art and culture. Yet Roy-Bhattacharya’s broad scope and cacophony of voices let his attempt to emulate a fundamentally oral art of traditional storytelling descend into incoherence.

The beauty of storytelling, according to Hassan, is that it is a mutual activity: “What matters is whether or not we can believe each other’s voices, and the test of that will lie in the story we make together.” With this tantalizing suggestion, he begins an engaging tale that entwines two separate plotlines. The first component addresses the disappearance of a foreign couple and the involvement of Hassan’s youngest brother. The second reveals how Hassan became a storyteller and delves into his family history. To solve the mystery, Hassan invites other listeners sitting around him to contribute their accounts of the vanished couple. The voices of the marketplace—of waiters, of a beggar woman and her daughter, of the local fortune-teller, of the fruit-stand operator, of a professor, of an art student, and more—are woven into the story one by one, thread by colorful thread. This method allows Roy-Battacharya never to reveal the solution to the mystery; he approaches it through many voices that corroborate and cancel each other out, ultimately questioning the nature of truth itself.

Even as these voices accumulate, Roy-Bhattacharya, a master storyteller himself, builds suspense by shifting his attention to a new speaker just as the previous one is about to uncover another element of the mystery. This constant delaying continues to beguile until the novel’s anticlimactic end, but it also leaves a lingering sense of disappointment. Still, the characters’ vibrant discussions on the nature of truth, beauty, love, and art add a level of continuity that counteracts the convoluted plot. Each voice adds new information on the foreign couple’s appearance and disappearance, and also offers a different perspective on the art of storytelling itself.

In this respect, “The Storyteller of Marrakesh” is very aware of its own status as a story. Each individual’s views on truth, beauty, love, and art color their interpretations of the disappearance, giving the narrative a satisfying thematic unity. By the end of the novel, there is a clearer idea of what happened, but after all the voices have spoken, they offer a broader truth that is as unstable as it is appropriate to traditional oral storytelling—no story is told the same way twice.

Presenting an oral story in print poses unique challenges to Roy-Bhattacharya, but he tackles most of them with stylistic verve. The novel recreates the experience of being told a story: each voice is rife with its own idiosyncratic ticks, hesitations, and rhythms. Lively heckling and interjections from the audience introduce another mimetic element to the narrative. One major flaw, however, is the lack of clear distinction between the alternating voices of the narrator, Hassan, and the other characters. In an actual experience of storytelling, each new voice would sound different and would therefore be easily distinguishable. Because no such variation is indicated in the novel, it becomes difficult to discern who is narrating. The layers of voices become difficult to follow and smear the overall aural effect into one of murky confusion.

Despite this ambiguity, Hassan’s story is well worth the read—if not for the eventual, somewhat nebulous resolution of the mystery of the foreign couple, then for the mesmerizing descriptions of Islamic art like tile mosaics, Berber music, and miniature portraiture. While “The Storyteller of Marrakesh” wavers in maintaining its coherence, it is the promising beginning to a series that will hopefully continue to offer insight into the Islamic world while avoiding the stylistic pitfalls of its first entry.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.