News

Harvard Quietly Resolves Anti-Palestinian Discrimination Complaint With Ed. Department

News

Following Dining Hall Crowds, Harvard College Won’t Say Whether It Tracked Wintersession Move-Ins

News

Harvard Outsources Program to Identify Descendants of Those Enslaved by University Affiliates, Lays Off Internal Staff

News

Harvard Medical School Cancels Class Session With Gazan Patients, Calling It One-Sided

News

Garber Privately Tells Faculty That Harvard Must Rethink Messaging After GOP Victory

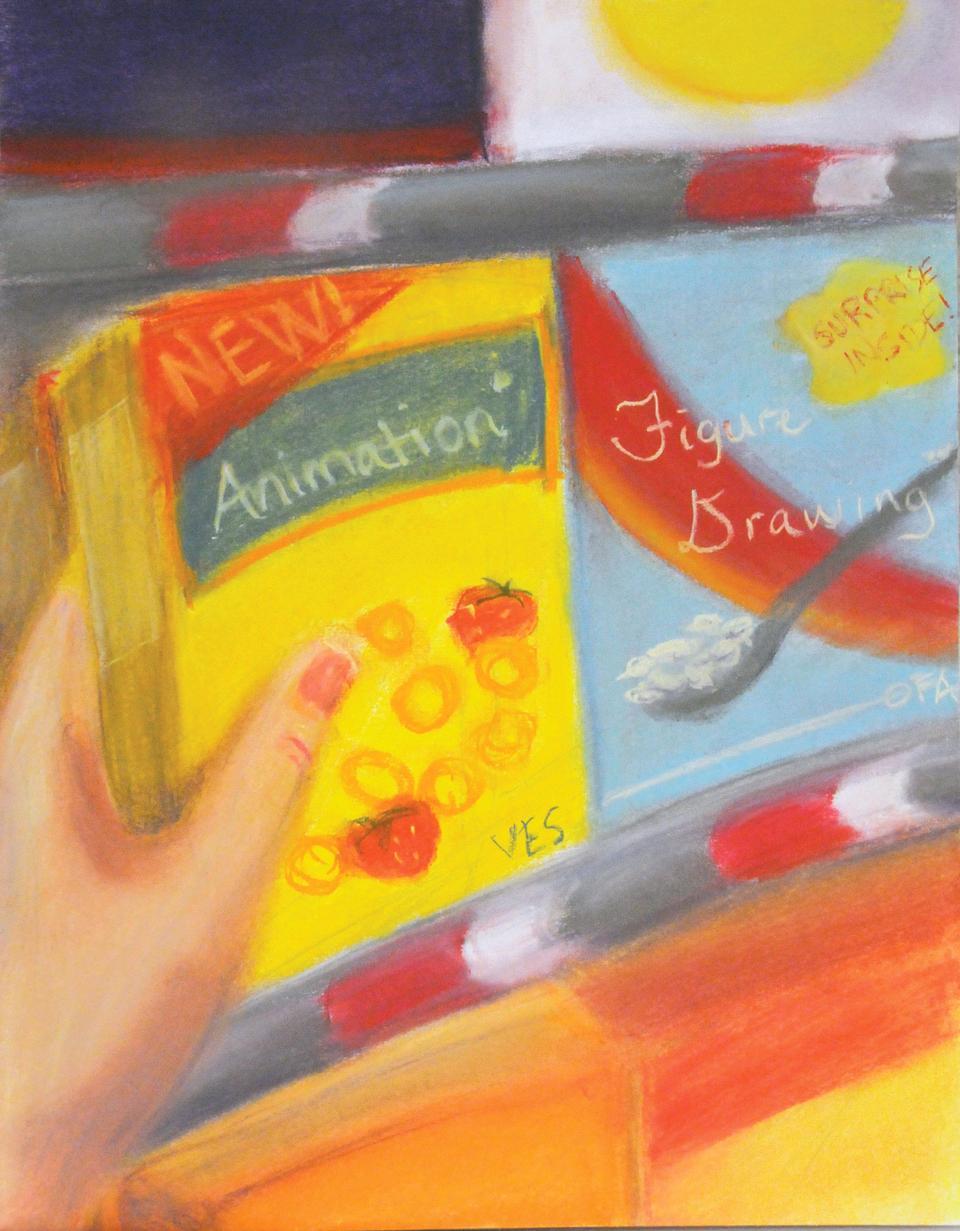

Beginner's Blues

Students must overcome limited resources to learn about the visual arts

“I don’t know if I would call painting so relaxing... you’re almost sometimes fighting with the paint,” says beginner painter Jane Chun ’12. Though she is a Visual and Environmental Studies (VES) concentrator, Chun had never tried painting before she took a studio course last semester.

Not all aspiring artists have as much access as Chun, particularly those who are not already in the VES department. Limited resources, further constrained by the financial crisis, have prevented the expansion of technical arts classes within the VES department and outside the academic curriculum—most notably in courses offered by the Office for the Arts (OFA). As a result, the few existing classes are forced to reject many applicants, and students who seek to learn a visual art form outside their concentration may be compelled to look for training outside the College.

Even Harvard students with no previous art experience regularly demonstrate enormous commitment to the visual arts, and many are extremely satisfied with their artistic experiences at the College. However, as with everything at Harvard, success in learning new skills within the visual arts can require an investment of blood, sweat, and tears.

A MYSTIQUE

The VES department currently lists 32 studio courses in the course catalogue; as with every department, many of these classes are not offered every year. Though 16 of them are open to students with no previous studio experience, all of them restrict class size to either 10 or 12 students, and VES concentrators usually receive preference over non-concentrators.

Katarina A. Burin, a Visiting Professor in the VES department, taught VES 10a: “Drawing 1” last semester, which had not been offered since fall 2007. According to Burin, over 40 people wanted to take her course, but she was only able to accept 14—two more than the department suggests for such a class.

“Unfortunately you can’t have more than about 14,” she says. “It just has to be, with resources [the way they are]. It started to be hard to get everybody’s work up on the wall. Unfortunately, there’s no way to allow for more.” At some point, inclusivity and high quality instruction become mutually exclusive options.

This cap prevents many from taking courses they would like to, although both professors and students insist that the classes are still accessible to people from all backgrounds. Burin determined admission to her class based on face-to-face interviews, then chose to admit people based on their enthusiasm and her desire to have a diverse class body. Just three of the students admitted were VES concentrators, and many were complete novices.

One of those novices was Pilar M. Mayora ’12, a Computer Science concentrator with no drawing experience, who wanted to learn the art in order to be able to do more work in computer graphics. “I was pretty happy that I had no experience,” says Mayora, who felt that her lack of background made her a perfect candidate for an introductory course.

Less compelling applicants weren’t so lucky. “I had two or three solid classes’ [worth of people] that could have been good.” Burin said. “They just don’t have the foundations classes anymore. It was clear to me that a lot of people craved direction and the basics.” Harvard’s tightening fiscal belt, however, makes an increase in the number of classes unlikely to happen anytime in the near future.

Despite the competitive admissions process, Director of Undergraduate Studies for VES Department Ruth S. Lingford disagrees that it is hard for students to get into VES classes, provided that they are committed enough. “There’s a mystique about how difficult it is to get into VES classes,” Lingford said. “I think students tell each other it’s difficult to get into a VES class. Some are very oversubscribed, but if students are willing to be broad-minded and shop a few different classes they can usually get into at least one.” It follows, then, that students interested in a particular art medium may have to settle for a different form.

MAKING SPACE

Outside of VES, students have the opportunity to take introductory visual art classes through the OFA. These extracurricular classes do not count for academic credit and are ungraded. Though the OFA has an extensive selection of ceramics courses, the only other term-time visual arts class offered is a figure-drawing course, which has been taught for 25 years by Boston professional Jon Imber. According to OFA Director of Programs Cathleen D. McCormick, the OFA is intent on providing classes for students who want to try something new as well as for advanced artists.

“Students have definitely expressed an interest in painting and photography,” McCormick says. However, she adds, “we were just about to pursue a couple of new art courses when the fiscal crisis hit, and we had to cut back.” McCormick points to the absence of a studio space with the proper ventilation for oil painting as a typical reason for the lack of a given class. On the positive side, she notes that last month the OFA offered a J-Term watercolor intensive course that helped to fill a niche in the curriculum. According to McCormick, seven of the students in that course had little or no art background, but were attracted by the chance to learn a new medium in the open January period.

Unlike other visual arts, the Ceramics Program at Harvard faces no shortage of classes or studio space. The program has an 11,000 square-foot studio in Allston for permanent use, and this semester alone is offering 10 studio courses, which is the same as the number of VES studio classes available. Unlike most Harvard art programs, ceramics classes are open to all undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, and staff at Harvard, as well as to members of the local community. Shawn L. Panepinto, the Acting Director of the Ceramics program, attributes its continuing strength to the presence of an engaged set of expert, intermediate, and novice potters. Registration fees for the program’s courses also help to cover its costs. Though ceramics classes sometimes fill up quickly, Panepinto says that the program always makes space for undergraduates.

Admission to the OFA’s figure drawing class is not as easy. According to Imber, about 30 students generally wish to take his class, but he can only admit 15. Admission is determined on a first-come, first-served basis. Nonetheless, Imber says that he has generally been able to find space for students who were very enthusiastic but late in signing up.

GOING LOW-KEY

The VES department and the OFA are united in their focus on students willing to sacrifice time and energy for a real understanding of an art. Many prospective artists, however, are not so ambitious. The Freshman Arts Advisory Board (FAAB) is a group of 15 freshmen that caters to this latter demographic. Rory Michelle Sullivan ’09, the Director for Residential Education and Arts Initiatives at the Freshman Dean’s Office, started the group last semester in order to get student feedback in establishing additional arts programming. The biggest message she heard from students who applied to be on the board was that there was a need for more low-intensity arts offerings. “A big priority that all the board decided was directing towards low-risk, low-commitment, low-pressure opportunities to just try and experiment with art,” she says.

This push for low-pressure engagement with art led the group to organize an event entitled “A FAAB Affair,” to take place tomorrow evening in the basement of Memorial Hall. The event is comprised of a series of workshops where students can come and learn crafts ranging from origami to ballroom dancing. According to Sullivan and FAAB member Kobi A. Rex ’14, the group hopes the event will interest people who are not generally involved in the arts and get them to try something new. “We want to have a bigger arts community on campus. We want to give them the ability to go low-key,” says Rex. In addition, FAAB is organizing a series of four- to eight-week workshops in subjects like figure drawing and documentary theater.

It was only last year that Harvard decided to invest the Director for Residential Education with the responsibility of getting freshmen involved in the arts. Though Sullivan is full of praise for the Harvard arts scene, she emphasizes the high demands it places on its participants and the alienation that it can have on those who just want to try something new.

“I do think it’s hard to find somewhere to just paint on a Saturday afternoon,” she says. “You can’t just go and use a Carpenter Center studio unless you’re in a VES class, and you can’t be in a VES class unless you get into a VES class and are willing to spend the time involved in a class commitment and are willing to use a space in your core schedule for arts.”

Lingford, however, disagrees that there is a large demand for low-intensity investment in the arts. “Harvard students are intense about everything,” she says. “When Harvard students are relaxing, they do it very intensely.”

TECHNICAL CONCERNS

Within the administration and faculty, then, lie several points of disagreement over the role of visual art in a liberal arts education at Havrard. These debates manifest themselves in opposing methodologies behind arts teaching itself.

For Imber, a self-proclaimed traditionalist, Harvard classes take the wrong approach to the visual arts. “A more formal education in the visual arts is ... singularly left out of the Harvard experience,” he says. “I think the perception now of students is that studio practice is not as important. It keeps being marginalized by some sort of elite of the art world.”

VES proponents tend to view arts learning in opposite terms. “We don’t really learn how to write a press release or a lot of very practical things, yet a lot of people who graduate from Harvard are able to do these things very very well, and a similar idea applies to the arts,” says Chun. “If you are interested in learning all the practical, technical stuff, there’s plenty of opportunity to do so through your own initiative.”

Regardless of pedagogy, one thing is clear. At Harvard, if you want to learn about the practice of art, opportunities exist for the motivated and amenable.

—Staff writer Chris R. Kingston can be reached at kingston@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.