News

News Flash: Memory Shop and Anime Zakka to Open in Harvard Square

News

Harvard Researchers Develop AI-Driven Framework To Study Social Interactions, A Step Forward for Autism Research

News

Harvard Innovation Labs Announces 25 President’s Innovation Challenge Finalists

News

Graduate Student Council To Vote on Meeting Attendance Policy

News

Pop Hits and Politics: At Yardfest, Students Dance to Bedingfield and a Student Band Condemns Trump

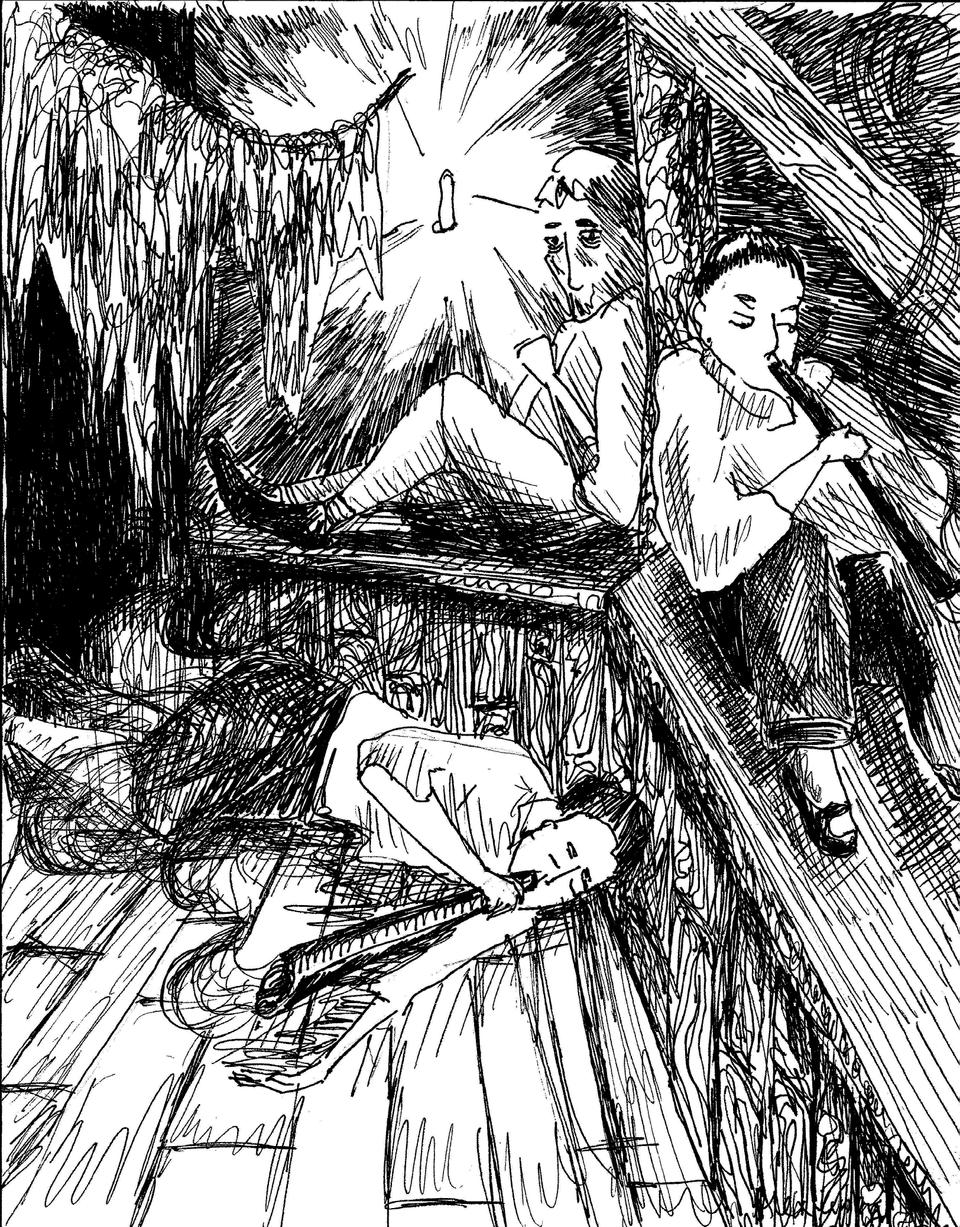

Ghosh's 'River' Is Shimmering But Shallow

'River of Smoke' by Amitav Ghosh (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

The gateway is a fickle symbol. Some gateways banish; others welcome. Sparkling opportunities and debilitating addictions alike have been labeled as gateways. To Bengali author Amitav Ghosh in his latest book, “gateways are not merely entrances and exits–they are tunnels between different dimensions of existence.” The second novel of his Ibis trilogy, “River of Smoke,” wanders through the gateways between various dimensions of cosmopolitan existence around the Pearl River during the years leading up to the Opium Wars of the early nineteenth century.

The novel is told mainly from the perspectives of four outsiders who have come, by design or happenstance, to the foreign enclave or “Fanqui-town” outside Canton, a city that simultaneously relies on international trade and denies all foreigners the right to enter. Its narrative, therefore, ranges over broad swaths of expatriate experience. One of its protagonists is an Indian opium trader, Bahram. Another is his loyal secretary, or munshi, Neel. The third is a French orphan named Paulette with a botanical bent who finds a mentor in an accomplished English gardener and horticultural tourist named Fincher. The last is a painter and Paulette’s childhood friend, Robin Chinnery, who has roamed far from home to find a real friend. With such a diverse cast of characters at its disposal, “River of Smoke” paints a historically sophisticated and obsessively detailed picture of cultural synthesis. Ghosh infuses each of their tales with terrific taxonomies of local tastes and pidgin tongues.

Yet the real heart of the story lies with the illegal opium trade, a practice that has just begun to cause friction between foreign traders and the Chinese government when the novel opens in 1838. Yet in his attempt to comment on the political altercations surrounding the trade, Ghosh neglects to endow his own language and characters with the same depth he gives to their meals and dialects. “River of Smoke” emerges as an ambitious yet shallow page-turner, a work that moralizes more than it moves.

There is an undeniable brilliance in those moments when Ghosh loses himself in descriptions of local flavors. “It had taken two days to prepare,” he writes of one delicacy served to Bahram, “and included some thirty condiments – crisp shoots of bamboo and slippery sea-cucumbers; chewy tendons of pork and juicy sea scallops; taro root and abalone; fish-lips and mushrooms – a symphony of carefully harmonized contrasts of texture and taste, it was reputed to have lured many a monk into breaking his vows.” Nor is Ghosh’s descriptive energy spent purely on the gastronomic arts; Fincher’s horticultural holy grail, the Golden Camellia, is treated with equal care.

Perhaps most impressive, though, is the way Ghosh represents the various voices of the inhabitants of the Fanqui-town. “‘Long time see no woman. No chance do jaahk,’” says one of Bahram’s sons in an English-Cantonese pidgin. “‘Ee’d have a bosun’s pay, and nothing charged for the victuals neither,’” offers Fincher to Paulette. A linguistic adventure in its own right, the novel demands readers rest content with a vague pseudo-understanding of its dialogue. This clever device inspires empathy with those foreigners removed far from their own linguistic origins.

But despite the variegated beauty of such descriptions and dialects, Ghosh stumbles when it comes to dramatic subtlety. Large passages of text seem to serve no purpose beyond heavy-handed exposition. The logical flow of the dialogue suffers a similar weakness, with conversations frequently beginning with the telling “As you know.” The author litters his prose with ad hoc explanations and details, rather than building a strong dramatic framework that would build expectation. The result is a somewhat unengaging narrative.

It may well be said, however, that the historical events themselves are not worthy of much more than Ghosh offers. Though the action of the novel centers around the opium trade, he only refers vaguely to the life-threatening and corrupting influences of the drug itself. For a novel entitled “River of Smoke,” experiential descriptions of the effects of opium are strangely few and far between. The two or three that Ghosh does include are limp instances of narcotic tourism embarked upon by Bahram. Instead of motivating his discussion of the run-up to the Opium Wars by engaging with personal narratives of the drug, Ghosh rather oddly chooses to focus on the bureaucratic bickering of the day. The protracted exchange of prohibitory edicts and vague statements of compliance statements between newly instated Chinese Commissioner Lin Zexu and the foreign businessmen involved in the opium trade is, frankly, just as dry as it sounds.

Of course, the politics of the debate are in fact intricate and intriguing; in another context, the issues of economic freedom and commercial colonialism could provide excellent fodder for fiction. Yet Ghosh never seizes the opportunity to explore these topics in depth. His rendering of the dialectic is condescendingly reductive; he twists the main players into good guys and bad guys, martyrs and traitors. The trader Charles King, who refuses to participate in the opium trade, is held up as a paradigm of commercial conscience misunderstood by his contemporaries. The new Commissioner is upstanding, uncorruptible, and magnanimous even to the foreigners that defile his land with their ruinous goods. Those who object to his policies against the opium trade might invoke principles of free trade in their own favor, but their truly mercenary motives are thinly veiled

Ghosh’s ambition to craft a sweeping, detailed portrait of the cosmopolitan Fanqui-town backfires at the expense of his characters. By lavishing attention on many characters at once, he hardly has time—even over an indulgent 500 pages—to develop any of them properly. Each has just a couple of defining traits, and that’s it. Bahram is illicitly successful but mildly conscientious; Neel is a curious polyglot; Paulette is eager and horticulturally gifted; and Robin is talented and of uncertain sexual orientation.

On a few tantalizing occasions, Ghosh offers glimpses of true insight. The novel boasts some genuinely funny moments, as when Ghosh pokes fun at superstition and puns about translation. “I too would be quite astonished if a young lady of tender years were to felicitate me on my dexterity in ‘polishing the ‘foc-stick,’’” Robin writes to Paulette, who is still growing accustomed to speaking in English. Other teases come in the form of melancholy, poignant reflections. Of the garishly decorated flower boats floating on the Pearl River, Ghosh writes, “in the bright light of day they looked … rather tired and melancholy, more tawdry than gaudy, humbled by the sun and ready to accept defeat in their unwinnable war against mundanity.” Such moments are frustratingly rare in a book filled to the brim with sexy yet shallow sketches of 19th-century cosmopolitanism.

—Staff writer Antonia M.R. Peacocke can be reached at peacocke@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

Where you should have gotten your protein since 1998.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

HUSL seeks to create and empower a community of students who are seeking pathways into the Sports Business Industry.