News

Harvard Lampoon Claims The Crimson Endorsed Trump at Pennsylvania Rally

News

Mass. DCR to Begin $1.5 Million Safety Upgrades to Memorial Drive Monday

Sports

Harvard Football Topples No. 16/21 UNH in Bounce-Back Win

Sports

After Tough Loss at Brown, Harvard Football Looks to Keep Ivy Title Hopes Alive

News

Harvard’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions Increased by 2.3 Percentage Points in 2023

Forced Withdrawals Come Under Fire

Part II in a IV Part Series

(Part I of this story appeared on March 22, 2010.)

When the Administrative Board informed Anna earlier this spring that she would have to withdraw from Harvard for two semesters, she was wholly unprepared for the tumult and anxiety that accompanied the process of withdrawal—an experience she characterized as “being thrown to the wolves.”

She had been in the middle of shopping week when the Ad Board, the College’s primary disciplinary body, delivered the news of her punishment for charges of academic dishonesty last fall. Anna—whose name has been changed to protect her identity—had to leave campus, hunt for a job, and find a new way to afford her prescription medication, which had previously been covered by the University.

Anna is not alone. Jeff, another Harvard student who spoke on the condition of anonymity, had failed two classes and was subsequently forced to withdraw in what he called a “very traumatic process.”

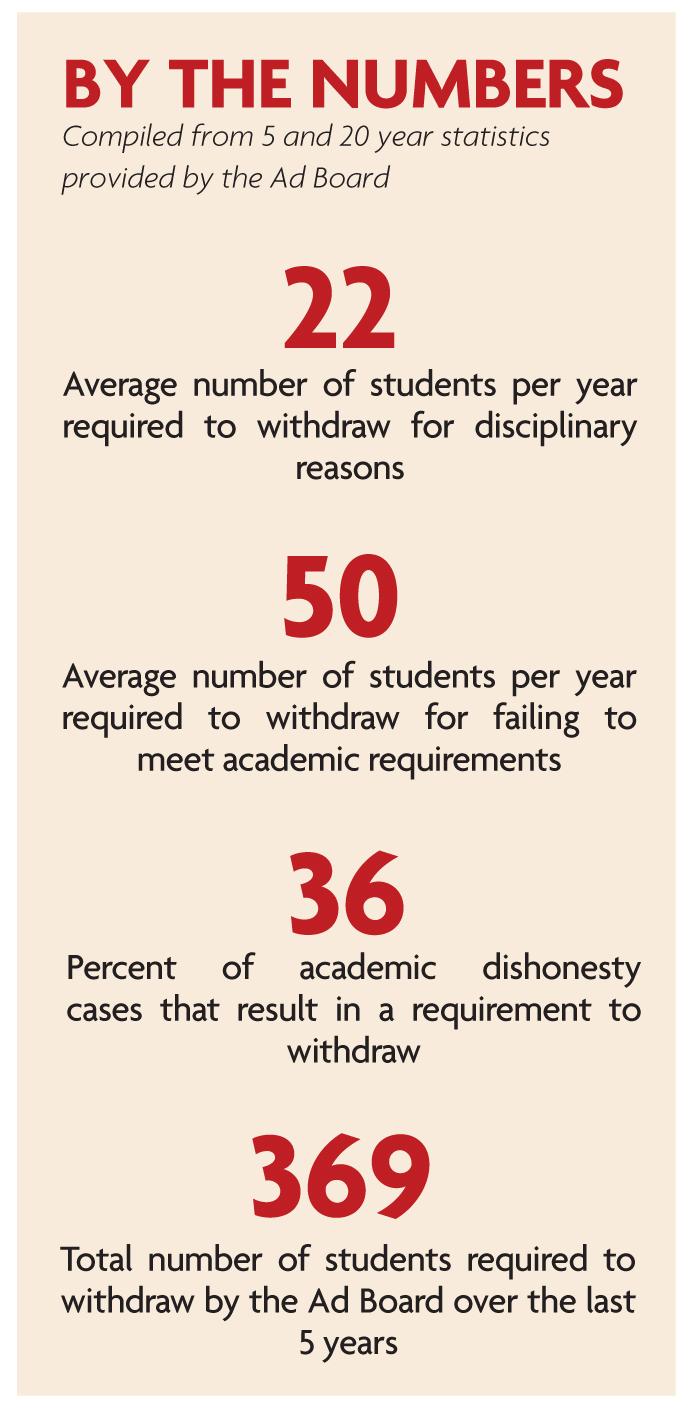

Their stories provide a rare window into the often overlooked consequences of withdrawal from the College. Every year, an average of 70 Harvard students face a “requirement to withdraw”—the Ad Board’s most common response to cases of academic dishonesty and a relatively standard response to serious academic failures.

College administrators say that withdrawal offers students a valuable opportunity to take a step back to reflect on their life goals and time at Harvard. But students like Anna and Jeff point to an array of potential problems in the withdrawal process, such as the punishment’s lack of relevancy to the original infraction, the sudden loss of health services at the University, and the pervading sense of isolation it instills.

If the Faculty of Arts and Sciences approves the recommendations proposed by the Committee to Review the Ad Board, the College will have a greater array of intermediate disciplinary measures at its disposal—likely leading to a decrease in the number of students who are required to leave campus.

The Committee recommendations offer a welcome change for students and faculty who feel that withdrawal is too harsh a punishment for most incidents of academic dishonesty.

But some students hope that the College will consider further reform that provides greater support for students who ultimately must undergo the withdrawal process.

“I wouldn’t wish the turbulence of this experience on anyone else,” Anna says.

“MIXED MESSAGES”

Students and administrators tend to disagree about the merits and drawbacks of a requirement to withdraw.

College administrators say that students should not view the requirement to withdraw as a punishment, but as an opportunity to retreat from the frenzy of the Harvard scene and reflect on their misdemeanors and life goals.

“It’s really designed to be a break...from the academic treadmill,” says Secretary of the Ad Board John “Jay” L. Ellison.

During their time away, students must hold a full-time paid job for six consecutive months—a requirement intended to encourage “a consistent pattern of behavior and success” in students, Ellison says.

The required withdrawal is in line with the Ad Board’s principle of pedagogical discipline, in which disciplinary actions are ultimately meant to be educational, rather than punitive, according to Ellison.

“Just having time to actually think about what they want from an education...is pretty unequivocally valuable,” says Adams House Resident Dean Sharon L. Howell. “I wish everyone would take a term off and think about that.”

But some students contend that required withdrawal is a flawed disciplinary response, as well as an ineffective educational measure.

Though Jeff—the student who had to withdraw after failing two courses—agrees that his removal from campus gave him the chance to gain fresh perspectives, he nevertheless says that required withdrawal is a “fundamentally stupid” process.

“It seems like its the default response to anything the [Ad Board] sees,” Jeff says. “But there was just a real failure to engage with the causes of [the original problem].”

The prevalence of the required withdrawal response is indicative of a “disconnect” between the Board and other offices in the College, such as the Bureau of Study Council—which could have been a far more effective on-campus resource for his academic problems, Jeff says.

“My year off didn’t really make me want to [do work for my classes] any more than before,” he says. “It just made me realize that the consequences are so bad that I never want to not [do work] again.”

While he was on the Committee, former Undergraduate Council President Matthew L. Sundquist ’09 says he had heard many “mixed messages” about the quality of students’ required withdrawal experiences: “I would say most students found the process to be confusing,” he says.

The discrepancy between the Ad Board’s perceptions about the effectiveness of required withdrawal and the negative accounts of some students may be, in part, the result of the Board’s primary source of information.

The Board mainly receives feedback on the withdrawal process through personal statements that students are required to submit to be considered for readmission to the College. But these evaluations may not be entirely reliable.

“I wrote all this bullshit about how I realized what a luxury academic study was,” Jeff says of his readmission statement. “It was true to a certain extent...but I absolutely omitted everything I thought [the Ad Board] didn’t want to hear.”

Ellison admits that students may feel pressured to write what they believe will cast them in a positive light for readmission, a position echoed by Sundquist.

“When...the reason for writing the statement is to be readmitted to the College, I think you can sometimes suspect and conclude that [students] are willing to take a one-sided view of facts,” Sundquist says. “I would too, if I were writing that statement.”

A GREATER RANGE OF DISCIPLINARY MEASURES

Recommendations from the recently released Report from the Committee to Review the Ad Board propose that the Ad Board be given a wider array of disciplinary responses to cases of academic dishonesty—including actions less drastic than required withdrawal, such as a penalty to a student’s grade.

A major driving force behind the recommendation was the Committee’s realization that withdrawal may be an excessive response in many cases, Sundquist says.

The report, which only addresses academic dishonesty policy, will not affect cases of forced withdrawal due to poor academic performance, as in Jeff’s case.

Though the Committee agreed that a requirement to withdraw can prove beneficial for some students, they felt that withdrawal may not constitute an “appropriate” response to most cases of academic dishonesty, according to Committee member Donald H. Pfister, professor of systematic botany.

“We felt there could be an educational moment [in many academic dishonesty cases] that right now wasn’t being realized,” Sundquist says. “If there are more different responses, we think there will be a lot fewer required withdrawals.”

A LACK OF SUPPORT

Thought the Committee’s recommendations may address the issue of matching incidents of academic dishonesty with the appropriate disciplinary response, the proposals are not a panacea for many of the difficulties experienced by students who do have to withdraw.

Anna says that the lack of support from the College during her recent withdrawal has led her to feel “completely discarded” by Harvard.

Anna had been seeing mental health therapists and receiving prescription medication from University Health Services, and says that she did not realize she would lose her health insurance through Harvard until she had only two days left of coverage.

However, the loss of insurance is a state-mandated law, according to Ellison.

“Our UHS staff help find students providers in the area and try to make certain the transition is smooth,” he says.

But Anna says UHS did not have readily available information to help her find an alternative health plan, and she left campus without the medication that she considers “vital” to her well-being. As of now, Anna is still uninsured.

“I’ve spent the most of these past three weeks struggling with [drug] withdrawal symptoms,” she wrote in an e-mail to her resident dean in February. “It seemed that the University went from caring whether I was chronically depressed or had any intentions of hurting myself to not giving a damn what happened to me now that I was on my own.”

Anna, who also addressed her suicidal thoughts in the e-mail, says she never received a response from her resident dean.

Indeed, some students complain that withdrawal cuts them off too severely from the College’s resources and campus life itself.

Students required to withdraw are supposed to have limited contact with the College during their time away, as “part of the goal is separation and reevaluation for the student,” Ellison says. “We do let the student know that we have every intention of having him or her return to finish.”

Howell says she tries to have “regular check-ins” with students in her House who have been required to withdraw.

But the amount of student-dean communication varies from dean to dean.

Jeff says that his House’s resident dean post was a “revolving door position,” occupied by four different people in the span of his dealings with the Ad Board and his subsequent two-term withdrawal.

Jeff characterized his required withdrawal as a “very isolating” experience: “You lose your Harvard e-mail address, you are forbidden to set foot on campus, forbidden to participate in any extracurriculars,” he says.

The sense of alienation can continue even after students return to campus, Jeff says, since many students required to withdraw gradually lose touch with many of their old friends and acquaintances back on campus.

“You have some spiel [for your peers] about why you were gone for a year, and of course it doesn’t mention the Ad Board,” he says. “But there’s always a hint of comprehension [in their minds].”

Anna and Jeff say they hope to see the College seriously re-evaluate the requirement to withdraw to improve the process for students in the future.

“The College is not a charity, but they should at least have enough ethical awareness to be supportive for the students they are asking to leave,” Anna says.

Administrators agree that the withdrawal process is not without its weaknesses. Howell, for example, called the question of medical insurance “one of the most difficult” issues the Ad Board deals with.

“It’s being thought about,” she says. “There’s definitely a recognition by the College that [the rapid loss of medical insurance does not create] an ideal circumstance.”

—Staff writer Melody Y. Hu can be reached at melodyhu@fas.harvard.edu.

—Staff writer Eric P. Newcomer can be reached at newcomer@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.