Beyond the Bucket

General wisdom is that the best strategy is the knock-and-wait. All Dorm Crew employees get a master key while out on the job. Only if there is no response, however, does a worker turn the key. Rachel V. Byrd ’13 is wearing sweatpants and an old T-shirt. Her hair is pulled back and her iPod touch is charged. Sometimes she has a water bottle with her, but today she doesn’t. Byrd, a Dorm Crew captain, is from Brooklyn, via the rural suburbs of upstate New York’s Sullivan County, and says she grew up helping her mom clean around the house. She lives in DeWolfe, and her stage presence permeates her everyday interactions. To pick her out of a crowded Lamont Café, she suggests you look for her dreadlocks.

The first moment of entrance into the room, when Byrd crosses the threshold in her close-toed shoes, is the only time when a student ever enters the room of another student without the latter’s permission, or even knowledge. But entering a room is a necessary step to entering the bathroom, and that is what Dorm Crew workers are there to do. Byrd likes to look around a suite on her way to the bathroom. She doesn’t touch anything, but she does think about what the people in the room are like, what their interests are, who they might be. One room in Claverly had a window seat, draped with chartreuse curtains and a poster of the Eiffel Tower on the well-organized and quite-full closet. The lampstand beside the bed on the left itself resembled the Eiffel.

“I bet they’re dramatic,” Byrd says on her way to the palm-tree-toothbrush-holder adorned sink. Looking above one of the beds: “And they have great scarves.”

Guys’ bathrooms, according to Byrd, tend to be cleaner than those of girls. “In guys’ bathrooms, you don’t find sanitary products which smell taking the garbage out; you don’t find makeup; there’s no hair in the shower and drain and on the walls.,” says Byrd. “Guys’ bathrooms are easy. I can expect a gross toilet. Girls’ bathroom I don’t know what to expect.”

Whether the occupants are in their room or not is a defining part of a bathroom-cleaning experience. If they are, there is the possibility of making friends, or conversation, or possibly just awkwardness. If they aren’t, there is the potential for solitude, reflection, or uninhibited dancing. This room is empty, and with bucket, broom, and Floorpol—Dorm Crew’s term for what is essentially a Swiffer with detachable pads—in tow, she locates, scans, and attacks the bathroom.

There are different approaches to gain the same end, though Dorm Crew does have some stipulations for how a room should be cleaned. First come the specifications about the supplies used. The blue spray, called Butcher’s Look, is for the mirror and fixtures. The Morning Mist spray, yellow rag, and yellow and green sponge are for the toilet, and only the toilet. The G-Force is multi-purpose. With the teal sponge and green rag, Byrd heads for the sink.

“Some Dorm Crew people don’t use gloves for anything, but I use gloves in the toilet—it’s common sense,” Byrd says as she goes for the latex-protected plunge.

Byrd joined Dorm Crew because unlike the other pre-orientation programs she was offered before coming to Harvard, Dorm Crew paid her. The opportunity cost of choosing the outdoor program, the arts program, or the urban program was too high. There are very few University-sponsored elements of campus life that accentuate a student’s financial status. All students have the same all-inclusive meal plan. Almost all students live in on-campus housing, allotted by lottery. Which students dine out, or join an organization with dues, or wear designer clothing, is outside the University’s purview. Students’ financial aid is private. The mere fact of being on financial aid is personal.

But Dorm Crew is an anomaly. Of the employees, 77 percent are on financial aid, and students—including those not in Dorm Crew—know it.

“Dorm Crew, like all other on-campus jobs, highlights the difference in economic means among students,” Dean of the College Evelynn M. Hammonds wrote in an e-mail to The Crimson, pointing out that nearly a quarter of Dorm Crew workers were not on any financial aid, and those who were on aid were not “the neediest” students. Hammonds has become a supporter of the program, though she once took issue with the way it heightened class awareness. In fact, no one suggests today that Dorm Crew be phased out; the program has become entrenched in campus life.

Yet Dorm Crew has managed to be both visible and inconspicuous. One of the first lessons during training is how to leave a bathroom. After the toilet, a worker turns to the floor. Instead of working on it from any angle, she must start in the back of the room and sweep toward the door, erasing her own footsteps as she leaves, “sweeping her way out.” No evidence is left. When the occupants come back to their room, it is as if she was never there.

“BIDDIES” AND BROOMS

Before Dorm Crew, first known as the Porter Program, came maids, known as “biddies,” according to Zachary M. Gingo’s ’98 junior history paper. Once a Dorm Crew captain, Gingo is now director of Facilities Management and Operations on campus.

The term “biddy” carries vastly different connotations today than it did then (Urban Dictionary’s sample sentence for the word: “Is that biddy wearing uggs in the summer?”). Harvard’s biddies simply cleaned the rooms of Harvard’s gentlemen, who were a decidedly priveleged bunch. But in the 1940s and 50s, as Harvard’s administration decided to aim for a more inclusive, merit-based admissions process, they created the Porter Program to bring more student employment opportunities to campus. In the wake of the second World War, the funds were particularly palatable to students whose tuition was covered by the G.I. Bill but had a wife and children at home to house, feed, and clothe.

“Did a student who worked a porter job feel like a servant for wealthier undergraduates?” asked Gingo, a student-worker himself when he wrote that question in his paper. But it was a different time. In an effort to maintain the maid service in place, the then-president of Harvard University Employees Representative Association argued that it wasn’t fitting for males to be doing the domestic, menial labor that befit women. The student government made a case that would be more persuasive to modern ears; as Gingo put it, “Poor students were forced, out of necessity, to become servants of their wealthy classmate.” Today, with a revamped and and unprecedented financial aid program, Harvard’s student body is less stratified. But many students are still drawn to the hourly wage that cleaning bathrooms offers.

THE DOERS

“Doing Dorm Crew helps my family to pay my way through college,” says Jason E. Sandler ’12, a captain who’s been cleaning dorms since his freshman year. He has a gray plastic bucket in his hand, containing the various spray bottles and sponges he just used to scrub the sink.

“To me the stereotypical captain’s parents are a librarian and a teacher—highly educated people without high incomes,” says Robert Wolfreys, Crew Supervisor in Custodial Services. Dorm Crew students often say that they worked before coming to school, so it seemed only natural that they continue to do so when they got here. Sandler helped out with jobs around the house, moving branches, shoveling dirt, caring for horses and dogs and cats. Byrd too was taught at home.

“You are certainly unafraid of getting your hands dirty,” says Erik C. Fredner ’12, a captain, of Dorm Crew workers. “It definitely takes a special kind of person at Harvard to be willing to go a scrub the toilet of a person they probably know.”

Wolfreys says that in his years of watching students go through the system, he has observed that those who stick with Dorm Crew have a little bit more humility and self-assurance than other students. Sitting at his desk in the back corner of the Dorm Crew office, he has seen students come to pick up toilet paper for their suites and ask for a dark bag. “They don’t want people to see them carrying toilet paper,” he says. Dorm Crew cleaners, on the other hand, walk through the yard holding a broom.

THE EXCHANGE

Dorm Crew has its perks. One is the flexibility. The Dorm Crew office is open from 9 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Monday through Friday and noon to 5 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. In any of those hours, whenever best fits with an individual’s schedule, that cleaner can go to a Dorm Crew office, sign out a key, and head to work.

“Say you’re working as a babysitter. They need you from whatever time to whatever time,” Byrd says. “Dorm Crew says we need four hours a week. I can give you those four hours whenever I want.”

Regular workers are required to work two hours each week of bathroom cleaning, known as “wet work.” Clean-up captains are required to put in four hours. But when those hours go in is each person’s choice, sometimes decided upon in the moment.

“My personal rule of thumb is I don’t like to clean on Saturday mornings because it is after Friday nights,” Byrd said. “I’ve done it once or twice and learned.”

Another perk, as mentioned before, is the paycheck. At $11.80, the starting wage is nearly four dollars above minimum wage, and students can work their way up to $12.70. In fact, Dorm Crew’s wages are so high that Federal Work-Study does not cover it; because the government pays 70 percent of an employed student’s hourly pay, the Dorm Crew rate would be too hefty a charge for the federal government.

Perhaps what is most appealing about Dorm Crew with regard to wages comes during Spring Clean-Up, after the school year has ended and the campus empties. In what sounds like an episode of one of The Learning Channel’s fast-paced-home-redecorating series, this is the time that dorms are scrubbed down for reunions. Regular workers work 40 hours a week and make roughly $450 after taxes. Captains often work up to 100 hours, and all the overtime hours are pay-and-a-half, so captains’ hourly wage of $12.80 is raised to $19.20. Add all that up, and students are walking away with paychecks for thousands of dollars. Spring Clean-Up, and some smaller scale projects throughout the year, are employment opportunities to which Dorm Crew workers get first dibs.

“You make a ton of money really quickly,” says Fredner, who added that he earned about $4,000 last Spring Clean-Up, in part due to a secret fifth week tacked on at the end. “In town,” he said, “I don’t know any job that would allow you to make much more than that.”

And students who do Dorm Crew are just as involved in other activities. When the program was first phased in from the maid service system that preceded it, Carroll M. Lowenstein ’82, one of three original captains, was also the captain of the football team. Byrd sings in Kuumba, plays in Padame, an African music and dance group, and acts. Sandler sings with the Glee Club and has G-chat statuses that read, “Conquer Cancer! Join a Harvard Relay For Life Committee today! Email me for details...”

“There is no real wealth but the labor of man.” Percy Shelley, whose portrait glowers from the top of the colored printer-paper arrayed on the wall of the Dorm Crew closet in Claverly.

“Work and acquire and thou hast chained the wheel of chance.” Emerson, opposite the spray bottles.

“Life grants nothing to mortals without hard work.” Horace.

“Our work is the presentation of our capabilities.” Goethe, by the bucket holding Floorpols.

“All work is noble; work alone is noble.” Thomas Carlyle, looking exhausted.

“To labor is to pray.” The Benedictine Order.

“As a cure for worrying, work is better than whiskey.” Edison.

Taped to the side of the supply closet, these posters articulate the Dorm Crew ethos—it is a job, but it’s something more. While not all Dorm Crew workers meditate on these mantras as they clean, the words still hang beside the supplies, and their prominence is not accidental. But when cleaners are on the job, civilian students do not see these epigraphs. They see a peer with a broom.

At its inception, Dorm Crew was more holistic than just the bathroom cleaning it does now, and bed-making and other services were included in a worker’s tasks though the 1960s. Some students felt, the Harvard Bulletin said, an “indefinable emotional repulsion toward the idea of their fellow students prowling through their beds and papers.” But that displeasure was not enough to offset the benefits of the program.

Today’s students sometimes also express hesitation about Dorm Crew, but for a different reason. While trust might be a major factor of Dorm Crew—master keys are powerful tools—workers’ integrities are not questioned. Instead, the question is the propriety of having a program that puts students in a position of serving other students in such a fundamentally menial way. Yale and Harvard both phased out their maid services in 1951, but while Harvard introduced the Porter Program, Yale instead asked all its students to clean up for themselves, according to Gingo’s paper.

“I think it is a concern on a number of levels,” says Meg Brooks Swift, the director of the Student Employment Office and Undergraduate Research Programs. “It is incredibly antiquated to think about how the system is set up. I think it is a very Harvard thing, and in 2010 it is amazing to me that it still happens.”

The awkwardness is apparent to Dorm Crew workers themselves when they are the ones opening the door. “It’s weird, yeah,” Kai Fei ’14, a novice worker, says of when his own bathroom is cleaned. “I mean, people come clean my room and I feel weird just sitting there.”

In an article in Harvard Magazine, printed in January 2006, John A. La Rue ’07 wrote about the door-knocking experience from the worker’s perspective. “Everyone knows that some students work hard every day just to be here, and others don’t,” he said. “It’s just a lot more comfortable when we don’t have to confront the personal realities of that gap. It’s a lot more comfortable when I knock and no one’s home.”

But Dorm Crew students say that though they have their awkward moments—walking in on students having sex, waking people up—it’s not unbearably uncomfortable. Dorm Crew cleaners generally say that they like Dorm Crew.

Sandler likes to make small talk with the people whose room he is cleaning. Others prefer when no one is home for reasons that have nothing to do with social discomfort.

“Amidst a busy schedule those, two or four hours may actually be the only few hours you have with yourself,” says Byrd. “You, your iPod. You can think about what you want. I’ll listen to church CDs, a podcast...it doesn’t have to be about the task in itself.”

The task itself also can be fulfilling. Much of what students grapple with at Harvard is intangible. Marx, Kant, Tolstoy, number theory. Success with such figures is difficult, if not impossible, to map, and after hours in a library, who is to say what progress has really been made?

“You are sitting there with some esoteric philosophical argument and getting nowhere, so it is this really satisfying work to then stand up and go to a bathroom and scrub the sink until it is clean,” Fredner says. The product is visible and indisputable. The labor put in leads to results.

“There is something satisfying about the last wipe of the mop and seeing how beautiful you have made that bathroom,” Byrd says.

When cleaning, Byrd uses a trick her mom taught her. When you wet something it looks cleaner, so she dampens a rag and runs it along the sink so that it shines.

“It makes you very thankful and appreciative of the other employees,” says Byrd of the experience of Dorm Crew. “Mostly because of Dorm Crew I make much more of an effort to thank, speak to, and have a personal relationship with everyone I meet in the dining-hall—the swipe lady, the cook behind the grill, the professional services, all the food catering services. It makes you a lot more aware and thankful of the other Harvard employees. And it’s nice. You feel like you have something in common.”

POST-IT NOTES

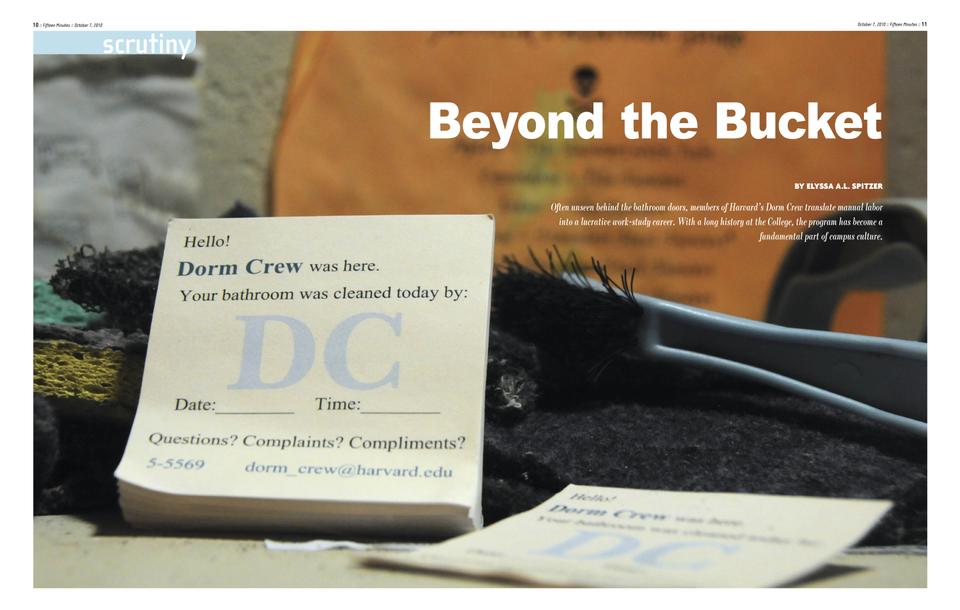

If Dorm Crew is an invisible phenomenon, cleaning that happens most often in empty rooms, the Post-it is the sole opportunity for a cleaner to express herself. The Post-it note is square, pale yellow, and reads, “Dorm Crew was here. Your bathroom was cleaned today by: ________. Date: _____. Time: _____. Comments, Complaints, Compliments, dorm_crew@harvard.edu.” Students often personalize their Post-its, and last year, Byrd’s personalization led to a correspondence with a student she didn’t otherwise know.

“I wrote something like ‘your porcelain throne was restored to its former glory by’ and that person wrote to Dorm Crew and say that I had made their day,” she remembers.

Byrd e-mailed the person who had responded to her Post-it, someone who turned out to be a senior boy, to thank him for sending in her first-ever compliment. Each time she cleaned their bathroom she left a creative Post-it, and each time he would e-mail back a funny comment pertaining to her note.

“Kirkland D-22—that was my favorite room to clean. Even though their bathroom was one of the worst, I knew they would appreciate my creativity. And they always had a speaker system set up so I could blast my iPod as I cleaned.”

“We’ve never met,” she adds of the boy. “We have never talked in real life.”

In Claverly, the room with the chartreuse curtains and Eiffel Tower lamp, Byrd filled out her Post-it and stuck it on the glass—“Once again, your reflection sparkles like the sun.” But the Butcher’s Look hadn’t yet dried, and the sticky on the paper, less intense than the crazy glue the inventor of Post-its was trying to create, didn’t hold the three-by-three pale yellow square to the mirror.

“It’s always frustrating if the sticky doesn’t stick because it’s the only proof of all the hard work you’ve done,” Byrd said as the paper fell to the ground.

She picked it up, dried the spot on the mirror, and put it on the glass again.