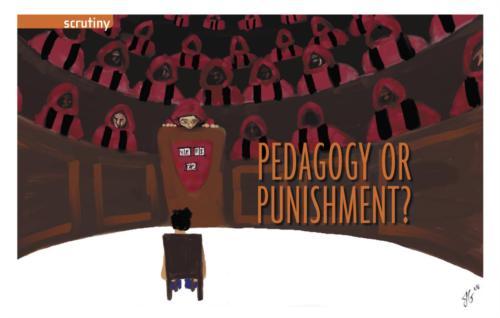

Tough Love

A rising sophomore was home for the summer when he received a shocking notification: he was facing the Administrative Board of Harvard College for academic dishonesty. Having never been taught proper citation procedures—not even in Expos—the student had included a bibliography in the first research paper of his Harvard career, but had not used correct citations in the body of the paper.

Until the receipt of this long-distance, post-term notice, the student was unaware that his work was of questionable integrity. He was never approached by the professor or the TF, and had left for the summer thinking that he had successfully completed his first year at Harvard.

Having been kept out of the loop so far, the student was first asked to send a statement offering his account of the incident to the Ad Board. He was also permitted to appear before the Board to make a two-minute verbal defense, a privilege that is allowed upon request but not generally encouraged. The student decided to take his chances and traveled to Harvard in order to argue his case, but with no access to his dean or other administrators until shortly before his hearing, even these attempts at mounting a defense hit a wall amidst a cryptic and seemingly-biased procedure.

“He got up here, and they were essentially like, ‘Well, I don’t really know why you came, because we basically already made our decision,’” says a friend of the student. At the end of this trying process, the student was required to withdraw for a year.

The frustrating results of this case contrast sharply with the Ad Board’s stated purpose, “to do what is best for both the student and the community,” according to outgoing Dean of the College David R. Pilbeam.

“You have a teaching institution, and you have a student who is trying to learn,” says the friend. “Can’t they say, ‘OK, well, you made a mistake, but…we’re going to teach you how to do it better,’ instead of immediately slapping someone on the wrist?” Ideally, the Board would be able to help students and community learn from mistakes, allowing everyone to benefit and look toward the future. Yet conversations with students and faculty reveal that behind the veil of secrecy, the Ad Board may be defeating the very goal it sets out to accomplish.

UNREACHABLE EDUCATION

Founded in 1890, the Ad Board’s objective is “the educational and personal growth of undergraduates.” Throughout its history, former Dean of the College Harry R. Lewis ’68 writes in his book, Harvard has tried to mentor its students through means of tough love. “Students tend to think of [the Ad Board] as the court where they will be tried and sentenced for serious offenses,” Lewis writes in Excellence Without a Soul. “For most of its history, however, it has seen itself as Harvard’s agent of practical moral education.”

The Ad Board is composed principally of the Allston Burr resident deans of each House and the resident deans of freshman, and is overseen by the dean and assistant dean of the College, with various faculty members and student advisers that attend meetings irregularly. The Board’s purview includes academic petitions, disputes between students, and, of course, disciplinary cases.

Given the breadth of the Ad Board’s responsibilities, its procedures are extremely intricate, making them difficult to render in even a 58-page pamphlet such as the Administrative Board of Harvard College Guide for Students. Practices vary from case to case—administrative petitions are typically handled by a smaller executive board, many cases are sent to subcommittees, and still others require the attention of the full Board. These multiple processes more than explain why it is so difficult for students to have a firm grasp of the current system. Says Matthew L. Sundquist ’09, the president of the Undergraduate Council (UC), “People have said that there might be something of a fine educational opportunity [in the Ad Board], which isn’t necessarily fully realized if students aren’t privy to the decisions that are made and why those decisions are made.”

A SHROUD OF SECRECY

This opacity doesn’t just make the Ad Board a feared institution among undergraduates, it also defeats one of its central aims: to educate students. Lewis writes that the Board rarely provides “any opportunity for education, which is, after all, what the disciplinary system is designed to accomplish.”

When a complaint is put before the Ad Board, a student is rarely informed that he is under scrutiny. Unlike in a law enforcement case in which the person under question is brought in for an interview during the fact-gathering stage, the Board usually inquires into the matter quietly, and without the participation of the accused. If the Board decides to act on the findings of its investigation, it promulgates “charges” and begins to assemble a formal case. Only once a full, written charge has been issued is the student brought into the fold. Before the student is even apprised of the situation, the Board has already acted as investigator, grand jury, and prosecutor.

Once the charges are finalized, the student is approached by his resident dean, shown the case against him, and told to compose a five to seven page statement, in which he “should draw lessons from what may have happened” and state if his actions “were in violation of a rule or standard of conduct in the College.” (In some cases, the students are also permitted to give an oral presentation.) From there, the process is out of the student’s hands while the Ad Board reaches a verdict and a sentence, which is relayed to him by his resident dean. Throughout, there is no contact between the Board and the student, and even those who have to take time off receive no official communication from the Board.

According to a witness, the case he was involved in seemed like a kangaroo court. “I felt like they had already decided the version of events they were going to accept as fact before actually engaging in the investigation,” he says, “and that because they had this singular notion of what had happened, they weren’t willing to consider anything—any statements, any hard evidence—that didn’t jibe with their preconceived sequence of events.”

Though John L. Ellison, secretary of the Ad Board, says that the Board will accept any pertinent evidence that students offer in their defense, the witness says it was difficult to introduce phone records that contradicted the timeframe put forth in the charge. In the end, the Board decided to review the phone records, but the disciplinary report they issued nevertheless presented an account of events indicating wrongdoing on the part of the respondent.

This sort of procedure, where a decision seems to have been made before all the evidence was collected, happens even more often in cases of academic review, students say. In a case that went before the Board last January, a sophomore whose grades were unsatisfactory due to health reasons was required to withdraw for a year. Though the student believes that she did benefit by taking time off, she says that she had not discussed her academic performance with her resident dean, and that there was little she could do by the time she was contacted. When she was ultimately asked to submit a statement to the Board, it was not to discuss whether or not she would be required to withdraw, but for how many semesters.

REVIEWS AND REFORMS

Since its founding over a century ago, the Ad Board has not formally altered its practices, save for the introduction of the Student Faculty Judicial Board in 1983. But the Judicial Board, whose mandate is to examine cases that have no Ad Board precedent, has met only once. Currently, it has no members.

The ongoing cry for Ad Board reform fell on deaf ears until last April, when then-Dean of the College Benedict H. Gross ’71 called for the development of a Faculty Review Committee. The committee was appointed by Gross’ successor, Pilbeam, and is composed of Professors Elaine Scarry, Stephen A. Mitchell and Donald H. Pfister, who serves as chairman. But because Scarry has been on leave since the committee was created, it has been on a “little hiatus,” according to Pfister.

The administration is beginning to seriously consider a review of the Board for the first time in years largely because of a student push for change. This fall, the UC established what it calls “the Ad Hoc Ad Board Committee,” which is comprised of three members of the UC and six students not serving on the council. Several members of the administration, including Pilbeam, supposedly serve as ex-officio members of the committee, though Pilbeam has never attended a meeting.

While the Ad Hoc Ad Board Committee and the Faculty Review Committee are working towards the same goal, they are not, as of yet, working together. Pfister maintains that he hopes to interact in some way with the other committee, but it remains to be seen how, if at all, this cooperation will ever occur.

“I’m not even sure that there will be recommendations for reform,” Ellison says. “I know that people feel like [the Ad Board] is broken. […] It’s not, but the information is not out there.”

CATCH-22

While Pilbeam, who chaired the Board for just several months, says he found the Board “effective,” members of the Harvard community—particularly those whose understanding of it comes from first-hand disciplinary experiences or second-hand horror stories—have a very different view. Even Ellison notes that the inaccessibility of the Ad Board to most undergraduates and faculty has left it with a bad reputation.

The sensitivity of many of the cases seen by the Board places its outreach efforts in a Catch-22. Because of the nature of disciplinary cases, little information can be released; as a result, few people can form a comprehensive understanding of the system, meaning that cases that may very well be outliers often come to be seen as typical.

Those in the know say that the Ad Board’s mysterious nature serves a purpose. Both Ellison and Pfister note that confidentiality is crucial to the function of the Board, not only for the protection of the students, but also due to the law. Students going before the Board must sign a confidentiality agreement promising to “respect the privacy of others involved and to refrain from discussing the matter or any of its details with anyone other than those who have a need to know.”

Students, however, see the lack of transparency of the Ad Board in a different light. The sentiments expressed by an upperclassman who served as a witness in a dispute earlier this year reveal the extent to which the cloaked nature of the proceedings alienates students. The secrecy, he says, is “just kind of a veil that they use to hide the fact that they’re not well organized, and they don’t actually spend much time on each case.”

If the purpose of the Ad Board is to educate the community, then the question arises: who has a need to know? Students who have been “adboarded” or involved in a case often refuse to discuss their experiences, and rumors abound that it is adboardable to talk about the Ad Board. With no information about its inner operations, students find themselves bereft of knowledge about the institution.

Pfister says that the Ad Board’s lack of transparency will be addressed by the Faculty Review Committee. “We should aim to make the process clear,” he says. “I think there is a little bit of a sense of it being cloak and dagger—how everything happens within that room, and it’s all bad. That’s probably not the case.”

But for many students who have faced the Ad Board, “cloak and dagger” sounds about right. On the forum set up by the UC Ad Hoc Ad Board Committee for students to anonymously post their experiences with the Board, the issue of secrecy pervades virtually all of the comments. “It is ludicrous that a body with so much authority over students should be secretive and accountable to no one,” one student post reads. “Actually, I am convinced that the Ad Board is a giant magic eight ball. That’s the secret they’re trying to hide.”

GOING FORWARD

Though both the faculty and student review committees have yet to release recommendations, the Ad Board has already seen one major change: the appointment of Evelynn M. Hammonds as dean of the College. Hammonds says that, as of now, she is not familiar enough with the Board to speak to its procedures and possible reforms. But with several exhaustive reviews and reports underway, there is little doubt that she will be acquainted with the Board before long.

However, the speed and depth with which future reforms will be implemented is less clear. For years, students and faculty have petitioned to change the structure and practices of the Board to no avail. While the Board may not survive in its current form, Jon T. Staff V ’10, chair of the Ad Hoc Ad Board Committee, notes that enacting changes may take time since “Harvard does move slowly, and unpredictably.”

But for the students who have had the misfortune of appearing before the Ad Board, reform can’t come quickly enough, despite the educational aims of the Board. Until transparency is increased, communication is improved, and sunlight is shined on the Board’s operations, there will continue to be a large segment of the student body who trembles at the mention of its name, rendering futile its attempts to seem less like an inquisition and more like a way to get students back onto the straight-and-narrow.