News

Garber Announces Advisory Committee for Harvard Law School Dean Search

News

First Harvard Prize Book in Kosovo Established by Harvard Alumni

News

Ryan Murdock ’25 Remembered as Dedicated Advocate and Caring Friend

News

Harvard Faculty Appeal Temporary Suspensions From Widener Library

News

Man Who Managed Clients for High-End Cambridge Brothel Network Pleads Guilty

Nicholas Kristof

Nicholas D. Kristof has lived a little more dangerously than most of his classmates who graduated in 1981.

The New York Times columnist has survived a plane crash in Uganda and an assault by drunken soldiers in Ghana.

Alums recall Kristof as one of the brightest undergraduates on campus—he graduated Phi Beta Kappa in three years and earned a Rhodes Scholarship. But he didn’t strike his peers as the type who would be held up at machine-gunpoint in Beirut and elude rebels chasing him through the jungle in Congo.

“I’m not surprised to see him emerge as the moral conscience of our generation of journalists,” says New Yorker staff writer and CNN senior legal analyst Jeffrey R. Toobin ’82, who worked on The Crimson with Kristof. “I am surprised to see him as the Indiana Jones of our generation of journalists.”

THE TRAIL FROM OREGON

Hailing from Yamhill, Ore., Kristof had never seen Harvard before he arrived on campus to begin his freshman year in 1978.

“I liked the idea of going to a famous snob college in the East, and Harvard liked the idea of getting a country hick from Oregon,” he writes in an e-mail.

Kristof’s Oregonian roots distinguish him from many of his colleagues today in New York. “He’s not rooted in the Eastern establishment in any sense of the word,” Toobin says.

The son of two professors, Kristof “was much more sophisticated than most of the farm kids that he grew up with,” according to Scott M. Androes ’82-’83, who knew Kristof in Oregon and became his freshman roommate.

“But they raised him to be very self-reliant,” Androes adds. Kristof took a year off between high school and Harvard to serve as a state officer of Future Farmers of America.

Kristof’s first foray into newspapering came about largely by chance.

“Some fellow eighth-graders at Yamhill Grade School in Oregon held an organizational meeting for a student newspaper. I hadn’t shown up, but nobody there wanted to be editor, so they elected me editor in absentia,” Kristof explains. “And I found I loved it.”

As a high-schooler, Kristof contributed stories to the local McMinnville News-Register. He gained the nickname “Chore Boy”—after the copper and steel scouring pad—according to Lance Robertson, a reporter for the News-Register at the time. Robertson says that Kristof’s writing astounded other staffers there.

“Here was this high-school student who was out-writing all of us,” he recalls. “Even as a high-school student, he was far ahead of everybody else.”

DIGGING IN

Kristof’s Harvard classmates remember him as a reserved, diligent student who focused on academics but who also held his own at The Crimson.

“I thought he was intelligent, retiring, and sweet,” says former Crimson editor Alexandra D. Korry ’80, now a partner at Sullivan & Cromwell. “He was very serious about his studies and very serious in general.”

Kristof admits, “I spent most of my time studying.”

“In the spring of my freshman year, I tried to study a million hours a week and also to work a million hours a week at The Crimson. It didn’t work, and I realized I’d have to choose. So I focused on my academic work and made The Crimson secondary,” he writes. “But I still spent a huge number of hours there, and I’d say that the people there were about the brightest of any group I’ve ever been around.”

Kristof was The Crimson’s “Campus News” tracker, following developments in higher education outside Harvard. He placed a particular focus on Boston University, where faculty and staff had recently gone on strike to protest the controversial policies of the school’s president, John R. Silber.

In opening one of his articles, Kristof wrote, “The critics of the Boston University (B.U.) administration have long regarded B.U. as the Iran of college campuses—intolerant, tyrannical, and prone to punish dissenters.”

Two-and-a-half decades later, Kristof would be detained in Iran—the BU of rogue states—after asking young people there whether they supported the Islamic revolution.

William E. McKibben ’82, a former Crimson president, says Kristof’s in-depth reporting on BU shares similarities with his writing in the Times today.

“He dug into a question like that when it didn’t seem to anyone at the moment to be of the absolute top urgency, and he showed over and over again why it was important,” McKibben explains. “It’s not unlike what he’s done with Darfur on the op-ed page of the Times.”

Dillon Professor of International Affairs Jorge I. Domínguez, who taught Kristof in Government 20, “Introduction to Comparative Politics,” recalls that, even as a freshman, Kristof was “already a superb writer” who had the markings of a budding journalist.

“Good listening is not always in big supply in a Harvard section, and he really was a good listener,” he says. “That also makes him a good reporter.”

Laurence S. Grafstein ’82, a former Crimson executive editor who is now head of global telecommunications at Lazard, notes that, although Kristof never held a leadership position at The Crimson, he earned wide respect for frequently helping out with “galley proofing”—a key part of the corrections process, which often lasted until 5 a.m.

“Galley proofing was one of the less glamorous jobs, and it’s a measure of his selflessness that he often volunteered for the job and never complained about it,” Grafstein says.

Kristof graduated in 1981 with advanced standing, a year ahead of the class with which he had begun his Harvard career. A few years ago, he formally switched his class affiliation to 1982. Kristof considers himself a member of the Class of ’81 who “escaped.”

ESCAPING ACADEMIA

Shortly after Kristof began his Rhodes Scholarship in 1981, he traveled to Eastern Europe on a vacation. While he was in Poland, the government declared martial law. Kristof, as Grafstein recalls, sent the first dispatch out of the country, stringing for The Washington Post.

His classmates who were still at The Crimson followed his coverage with bated breath, unsure if he would be safe.

But one thing was sure: Kristof couldn’t be held in an ivory tower.

At Harvard, he says, “I was a bit disillusioned with my Gov classes, because, although I did very well in my international affairs classes, I felt that came from an ability to spit out good test answers rather than from really understanding the texture of foreign societies.”

“Later, when I was at Oxford, I began traveling during vacations—backpacking and filing freelance articles—and I realized that I was learning much more by traveling than I had in the classroom,” he writes.

His classmates had thought the high-achieving Kristof was destined for an academic life. They soon recognized that his future lay in newsprint.

Bill Keller, executive editor of the Times, says Kristof is unmistakably a journalist.

“I’ve always thought of Nick as someone whose interests are widespread and various, who could change subjects on a dime,” says Keller, who first worked with Kristof during the late 1980s, when they were both reporting in Asia.

“If you go into academia, you’re expected to master your subject...until you’ve clocked enough time and can teach that subject until you die. Journalists are exactly the opposite,” he explains. “Journalists all have a little bit of ADD.”

THE HOLY GRAIL

As a economics beat reporter in the mid-1980s, and later as a foreign correspondent and columnist traveling to over 100 countries, Kristof has displayed a “gift for getting to the heart of the matter,” says Susan D. Chira ’80, foreign editor of the Times and a former Crimson president.

At least since he covered Poland in 1981, Kristof has frequently found himself in risky situations.

“We used to joke that, if you were traveling with Nick, you wanted to stay very close with him, because danger was always a short distance away,” Grafstein says. “He just has this incredible knack for being close to incredible news stories.”

Chira adds, “Nick has always been interested in places that are more remote, less explored.”

He’s especially fascinated by developing countries with shaky governments.

“If we get a bad president in the U.S., then our federal deficit goes up and prisoners are abused in Guantanamo,” he writes. “When Sudan gets a bad president, then hundreds of thousands of people die in genocide.”

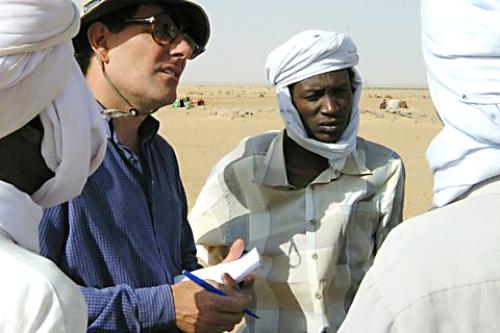

And as hundreds of thousands die in an ongoing Sudanese genocide, Kristof has been there to chronicle it.

This past April, he won his second Pulitzer Prize—the journalism world’s equivalent of Indiana Jones’ Holy Grail—in part for his Darfur coverage.

He and his wife, Sheryl WuDunn, had previously won a Pulitzer in 1990 for their coverage of the Tiananmen Square democracy movement.

Although that places Kristof among a handful of journalists who have won two Pulitzers, he writes that “the most fulfilling moments haven’t been the prizes, but the sense that I’ve made a difference on some issues.”

“I think that my columns on Darfur helped put the issue on the international agenda, and that’s satisfying—but it would be much more so if the situation actually improved on the ground,” he writes.

“Frankly, the most influential work I ever did was an article back in 1996 on ordinary third world ailments that kill lots of people,” Kristof adds. “Bill Gates happened to read the article at a moment when he was wondering how to reorient his foundation, and he credits the article—actually, the chart that went with it—with helping him think about using his foundation to address public health issues in the developing world.”

And even though Keller says “journalists all have a little bit of ADD,” Kristof has remained steadfastly focused on developing-world health issues.

He answered all this reporter’s questions via e-mail from Namibia and Swaziland, where he was reporting on the AIDS epidemic.

—Staff writer Daniel J. T. Schuker can be reached at dschuker@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.