Harvard’s Secularization

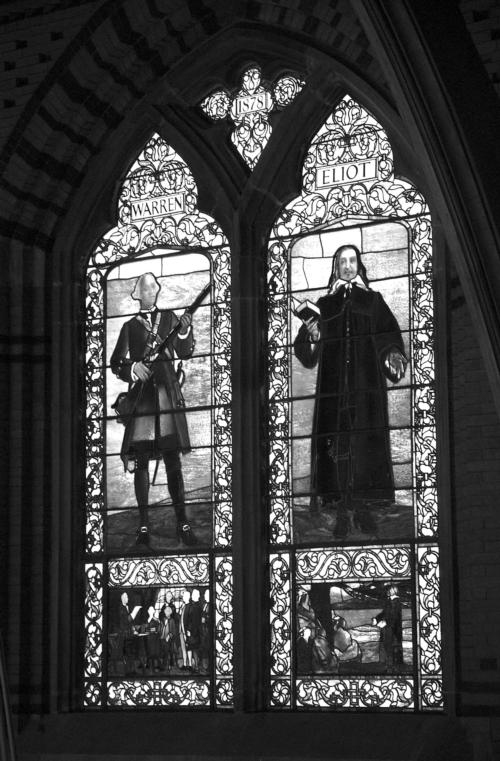

Harvard has never been shy about honoring its traditions. From the stained glass windows of Memorial Hall to the bright red bricks that line its storied buildings, the University likes to keep its relics intact.

Well, most of them.

Ironically, the Crimson shield—the University’s logo and the ostensibly eternal distillation of its identity—has undergone significant change since the University’s birth back in 1636.

Back then, it wasn’t just about “Veritas.” It was “Veritas pro Christo et Ecclesia;” not just Truth, but Truth for Christ and Church.

What exactly happened to “Church”? And where did Christ go?

It used to be that Harvard had only one business—training young men for deployment into the ministry. And it wasn’t overnight that it transformed into the famously secular research university we know today.

Rather, the movement gathered momentum gradually, propelled by intellectual leaders who, while using Christianity as an implicit foundation, believed above all in the advancement of scientific and academic knowledge.

For the Puritans who founded the College, separating God from academia was unthinkable. “The whole notion of a secular entity was unheard of,” says Plummer Professor of Christian Morals Peter J. Gomes.

Indeed, Harvard’s “Rules and Precepts” of 1646 hold that “the maine end of [a student’s] life and studies is, to know God and Jesus Christ which is eternal life…the only foundation of all sound knowledge and Learning.”

By the 19th century, Harvard was undergoing a liberalization of its religious ideas under the influence of the Unitarians, who had come to control Harvard and institutionalized a greater emphasis on reason, morality, humanism, and intellectual freedom. “Unitarianism is a much more broad-based, hospitable religion, at odds with the old Calvinists,” says Gomes. “[The movement] led the way to what eventually became a secularizing process.”

Gomes says the sea change came in 1869 with the inauguration of University President Charles W. Eliot, who drew on Unitarian and Emersonian ideals in laying out a revolutionary treatise of higher education. “The worthy fruit of academic culture is an open mind,” Eliot said, “trained to careful thinking, instructed in the methods of philosophic investigation, acquainted in a general way with the accumulated thought of past generations, and penetrated with humility. It is thus that the University in our day serves Christ and the Church.”

The University’s purpose, in other words, was no longer anchored strictly to theology.

But while compulsory chapel attendance may have already become ancient history, Harvard wasn’t abandoning God just yet. In fact, one could regard the ostensible secularization of the late 19th century as more an affirmation of Christianity than an unequivocal rejection of religion. As George M. Marsden writes in “The Soul of the American University,” the shift was not occurring “in the name of an attack on Christianity but under the banner of its expansion.” In effect, he writes, whatever Harvard did simply was Christian.

“A student in 1970 and a student in 1870 were educated in very different ways,” says Daniel E. Luxemburg ’07, who will be writing his thesis on the shift. “But regardless of the era, there’s an idea that an institution can and does reproduce knowledge objectively in students.”

In response to those who criticize the role that Christianity plays in a university that is officially unaffiliated, Gomes says, “What annoys some people is that the symbols are still very evident...We have a divinity school, I’m the Plummer Professor of Christian Morals. The Christian identity cannot be, and in my opinion, should not be, eradicated. We founded the place, we’re here, and I’m grateful that we’re surrounded by other entities, but I don’t apologize for the fact that there’s a church in Harvard Yard.”

Amanda L. Shapiro ’08, the chief recruitment officer of the Harvard Secular Society, says she doesn’t “find the Christian presence too overwhelming,” even if it was a little harder to avoid on Ash Wednesday.

As President Eliot wrote in 1886, “A university cannot be built upon a sect”—unless that sect includes all the “educated portion of the nation.”

Indeed, the active presence of groups like Christian Impact, Hillel, and the Islamic Society is a clear indicator that though the Harvard we know today is more likely to leave its proverbial cross on the bedstand than dress up in its Sunday best, it is by no means a godless institution.

As University President Lawrence H. Summers said in his 2002 commencement speech, from Harvard’s beginning, “Veritas meant divine truth, truth reached ultimately not through reason but through faith.”

Yet, in 1878, The Crimson reported a remark about the “Veritas” seal made by one Dr. Holmes at a Harvard Club dinner in New York. It might well serve as our maxim in 2006: “The Harvard College of to-day wants no narrower, or more exclusive motto than truth—truth which embraces all that is highest and purest in the precepts of all teachers, human or divine.”