News

Harvard Grad Union Agrees To Bargain Without Ground Rules

News

Harvard Chabad Petitions to Change City Zoning Laws

News

Kestenbaum Files Opposition to Harvard’s Request for Documents

News

Harvard Agrees to a 1-Year $6 Million PILOT Agreement With the City of Cambridge

News

HUA Election Will Feature No Referenda or Survey Questions

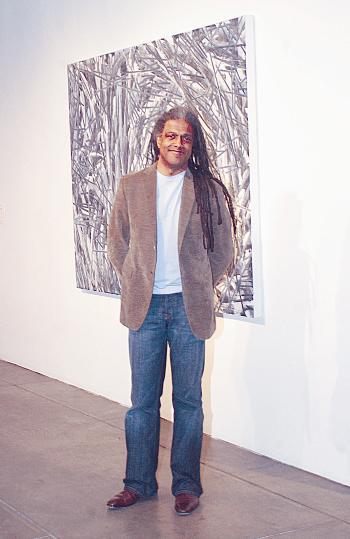

Elvis Mitchell Takes on Harvard

World-renowned film critic brings a fresh perspective on film

Elvis Mitchell likes to disarm. Even in person, the same arresting wit he unleashes on readers and fearful filmmakers in his New York Times reviews arrives untrammeled.

“Am I keeping you up?” he quizzes me minutes after sitting down at the Carpenter Center’s Sert Gallery café. “You look like you’re dozing off. I can get you a cup of coffee.”

Actually, there’s no real danger of nodding off around Mitchell, who is at once relaxed, mock-confrontational and boisterously intellectual. His latest incarnation this semester as Visiting Lecturer in Visual and Environmental Studies (VES) and African and African American Studies—during which he’s keeping up his New York Times gig—hasn’t tamed him a bit.

In conversation, he releases a dizzying arsenal of cultural allusions and florid vocabulary in deadpan. As regular readers of his reviews know, Mitchell habitually shreds dichotomies between high and low culture.

He also resists any characterization that he tends towards pop culture while fellow Times film critic A.O. Scott, who came from book criticism, leans highbrow. “I don’t know if Bring it On came from a book,” he says. “Maybe it did. But A.O. Scott is starting to be the house Kirsten Dunst writer.”

ACADEMY AWARDS

Today Mitchell could be dressing the part of the professor as avant-hipster, in a chic pale blue sweater, cocoa blazer and thin-rimmed glasses with a quirky pointed bridge. Mitchell’s two classes at Harvard this semester, VES 173x, “American Film Criticism” and Afro-American Studies 183, “The African American Experience in Film 1930-1970,” drew substantial crowds. The former, originally capped at 50, was changed to open enrollment, and109 undergraduates are currently taking the course. Students in the class, while enduring some organizational hurdles due in part to a larger enrollment than expected, have mostly remained enthusiastic about Mitchell’s arrival.

Escaping to the academy, even if it’s only for a Thursday shuttle romp, allows Mitchell to flex his position in what he calls “the DMZ between doing advocacy journalism and doing a lengthier exegesis that would be more academic.”

His classes similarly hover between the popular and the academic. Meanwhile, Harvard has a rep for being historically conservative about cultural studies, and it’s taken until this year for steps to be taken toward a film studies program. Asked to make a stump argument for studying pop culture in the academy, Mitchell groans. “Gee, do I have to?”

But then he obliges: “There can be a kind of mustiness to academic writing, a sort of reiteration of what’s gone before, and there’s a whole level of exuberance and mythology that’s not being written about that can be found in pop culture.”

DuBois Professor of the Humanities Henry Louis “Skip” Gates Jr., chair of the Af-Am department and no stranger to public intellectualism, tapped Mitchell in his effort to rebuild the department after several high-profile departures. After meeting the film critic at a dinner in London and bringing him to Harvard for lectures last year, Gates declares himself an unqualified fan.

“We wanted to hire someone to teach film, but we also just wanted to hire Elvis Mitchell,” he says. “There’s nobody quite like him.”

“And,” he adds, “how could you not love a black man whose first name is Elvis?” Mitchell was game, but at a time when Gates was said to be contemplating a permanent move to Princeton, he was also wary.

“Look, if I had seen a ‘For Rent’ sign in his window I would have been a little concerned about that,” Mitchell says now. “But he assured me that that was not the case, that he was still committed to this place. That was the reason I came, because he invited me. And I think he’s a wise enough host to know that if you invite someone over to a party, you don’t go out to see a movie.”

It doesn’t seem to faze Mitchell that his host has chosen to spend this year on leave at Princeton’s Institute of Advanced Study, nor that, according to Gates, the two haven’t spoken since Mitchell arrived at Harvard last month.

“I knew he was going to be at Princeton before I agreed,” says Mitchell. “It wasn’t like I was like, ‘Wait a second! This isn’t a Boston number!’ He can be found.”

In an interview with The Crimson last Tuesday, Gates expressed a desire for Mitchell to return to teach after the spring, though the current arrangement is for a semester.

“That’s news to me, actually,” says Mitchell, slightly taken aback. “I mean, this is just something for me to try out. I don’t have any plans beyond this semester.”

RENAISSANCE MAN

Agreeing to teach without taking a leave from the New York Times and continuing his radio appearances means an inevitably frantic schedule. Mitchell is matter of fact about the plan. “I’ve always found that the busier you are, the more able you are to portion your time to get things done. But I’m sure that’s old news to you Harvard people,” he says.

For him, the attraction of Harvard lay also in the opportunity to talk about film irrespective of commerce.

“One of the things I’ve learned the hard way at the New York Times is that people want to know if they should go see a movie or not,” he says. “They don’t necessarily want the philosophical explication of how this movie fits into the pantheon or whether or not it’s canonical. They want to know if they should spend 10 bucks.”

After the deal was closed, Mitchell brought several ideas for classes to Gates, who consulted Kenan Professor of English and VES department chair Marjorie Garber. They decided together on the lecture and the seminar.

“I wanted to make these classes as much about a dialogue with students as possible,” says Mitchell. “I feel like I want to get something out of it too. If I want to hear my own voice, I can turn on NPR or pick up the paper.”

Mitchell says that screening films in advance, without an audience, means he often feels cut off from the public. “There’s an insularity in film criticism,” he says. “And I want to know what’s going on. By going out to festivals and teaching these classes, the calcification process is being retarded.” He pauses. “I hope.”

Mitchell says he was drawn to film writing in the first place by the underground film movement of 1960s and later blaxploitation films. He remembers reading reviews in high school of Caddyshack and complaining that the critics who decried the film had all missed the point. “I’ve always wanted a chance to write about culture in a way that wasn’t being done for me coming up,” he says. “I just felt like that perspective wasn’t being represented anywhere. It kind of is now, everywhere, I’m probably too late for the party.”

He wasn’t too late for the newspaper of record. When then-chief film critic Janet Maslin retired in 1999, the Times opted to replace her with a triumvirate of critics that includes Mitchell, Scott and Stephen Holden.

“There was an understanding that they wanted things to start changing,” Mitchell recalls. “They wanted people there who were interested in what was happening in the culture, who could take the pulse and put that in the paper. The New York Times no longer pretends that we are the last bastion of mid-seventies thinking. We understand that people watch television and listen to these CDs, and go out, and don’t just go to theater all the time.”

RACE RELATIONS

Harvard’s African American studies department has been visibly bruised by the confrontation two years ago between former professor Cornel R. West ’74 and Harvard president Lawrence H. Summers that drew national attention for its racial dimensions. Mitchell arrives here from a newspaper that has suffered its own public scandals of late. When the young black reporter Jayson Blair was fired last year from the Times for fraud and plagiarism, it led not only to the resignation of the paper’s two top editors, but to outside accusations that Blair was affirmative action’s cautionary tale.

Though Mitchell expresses concern that the Blair incident was used to condemn the hiring of African-Americans at newspapers, he says that at the Times, he is “incredibly well supported. My being a person of color has not been an issue. I was not an affirmative action hire.”

Mitchell says it was an issue for a handful of readers who called the Times to slam its decision to hire a black film critic.

“The only reason they knew I was black was because they saw me on television,” he says, bemused. “It wasn’t like I was leaving the g’s off of my action verbs and all of a sudden they could tell that I was a black guy. I guess racists also want to know where all the news that’s fit to print is coming from.”

As a widely respected and established African-American journalist, however, Mitchell is more than willing to be a role model. “I think the great thing about me being at the New York Times is that I set an example,” he says. “So people like me who are coming up who never thought they could have a job at The New York Times, that’s now something that that black people do.”

Even as African-American culture becomes a known commodity of the mainstream in music and fashion, Mitchell argues that films by and for African-Americans remain inhibited by financial obstacles. “We’re told that African-Americans only want to see movies where there’s gunplay,” he says. “There are also found wisdoms that a black film will only make so much money, so we can only release it in so many theaters, so we can only spend so much money to make it. And the great thing about a movie like Barbershop 2—at least in it being released in 2,700 theaters last week—is that it proved that that is not true.”

Despite recognizing this milestone, his Times review of the film was less than glowing, criticizing it as an overtly commercial, unfunny rehash of the original. But Mitchell maintains hope that black film will someday enjoy a renaissance from the underground.

“There’s still yet to be a black version of the art house circuit that serves essentially as being on the best triple-A minor league baseball team and being summoned up to the majors,” he says.

For now, there’s Barbershop 2 and countless other Hollywood vehicles of every stripe, which Mitchell has to watch in ever-growing numbers. It was widely speculated that Maslin, his predecessor at the Times, retired in part because of burnout from seeing too many shoddy films.

Whether or not this is true, Mitchell finds the idea laughable.

“Oh god, it’s so hard seeing bad movies!” he laughs. “My father worked two full time jobs until he retired. I see two bad movies in a day. What am I going to do?” He shakes his head. “The good movies make up for the bad movies.”

Sadly, he hasn’t reviewed any of the recent, stellar crop of Harvard-related films. “I didn’t realize this was a pattern,” he says, frowning. “I have to address my movie viewing vis-à-vis films about Harvard.”

He does want to know which is truer to life—Legally Blonde or Harvard Man—and when I pick the former, he considers it.

“So is there room for an innocent like me or Reese Witherspoon around here? That would be my question.”

—Staff writer Irin Carmon can be reached at carmon@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

With innovative financial tools combined with financial education, Collegiate empowers students to take control of their finances and build confidence in their money management skills.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

Admit Expert is a premium MBA admissions consulting company, helping candidates secure admission to top B-schools across the globe with significant scholarships.